This discussion and review contains spoilers for Westworld season 4, episode 4, “Generation Loss.”

Westworld has always been a show about stories. Much of the first season was obsessed with the “narratives” within the park. The theme park’s head writer, Lee Sizemore (Simon Quarterman), became an increasingly sympathetic and nuanced figure over the first two seasons. After the third season killed off the show’s protagonist Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood), the fourth season reintroduced Wood playing a writer named Christina, struggling to tell stories that mattered to her.

Even though Christina is nominally a new character — albeit one played by a familiar face — there is a sense in which she has always been central to Westworld. In publicity for the first season, series co-creator Jonathan Nolan conceded that Andrew Wyeth’s 1948 painting Christina’s World had been a major touchstone for the character of Dolores. Now, in a very real way, Westworld is Christina’s World. There is something unusual and interesting about the seeming mundanity of Christina’s life.

In interviews before the season began, co-creator Lisa Joy joked about how writing for Christina was a departure for the show. “We’re just along for the ride with her as she experiences the city, dating, being a writer,” Joy explained of Christina’s life. “It’s really nice to be able to not speak wholly in metaphor, to be able to do something contemporary and human, to write roommates, banter and bad dates. I haven’t been able to do that yet.”

Of course, Joy isn’t being entirely sincere. Much of the season has explored Christina’s growing sense of unease about the nature of her reality, as she has begun to pick at the edges of the world in which she has been placed. However, there is a sense that Christina’s world is bigger than the theme parks that dominated the first two seasons. Indeed, the reveals in “Generation Loss” suggest that Christina is living in a world as “real” as any that exist after Charlotte Hale (Tessa Thompson) enacted her plan.

The first two seasons of Westworld were about the Delos employees imposing their narratives on the hosts within the park, as well as about characters like Dolores attempting to assert their own agency over the stories in which they found themselves. In the fourth season, the dynamic has been deliberately inverted. Taking her cues from what characters like Sizemore did in the theme park, Charlotte has effectively conspired to impose her own story on the outside world.

“It’s time for a new narrative,” Charlotte explains to Caleb (Aaron Paul), and it becomes clear that Charlotte’s evil scheme is effectively about trapping the outside world within a familiar narrative. “Generation Loss” makes it clear that Christina is still living within a narrative that isn’t too different from the one that Dolores lived inside the theme park. Her blind date (James Marsden) even catches a dropped object by way of introduction, like Teddy (also Marsden) did in his theme park loop.

“Generation Loss” is not particularly subtle in making its point. Christina’s date talks about his life in a way that works as a metaphor for the experience of the hosts within the theme park, but also as a more general statement on the human condition. “Every day you wake up, do your job, and go home,” he reflects. “Rinse and repeat. Like a train, circling the smallest track.” It suggests an equivalence between humanity and the hosts, something the episode repeatedly reinforces.

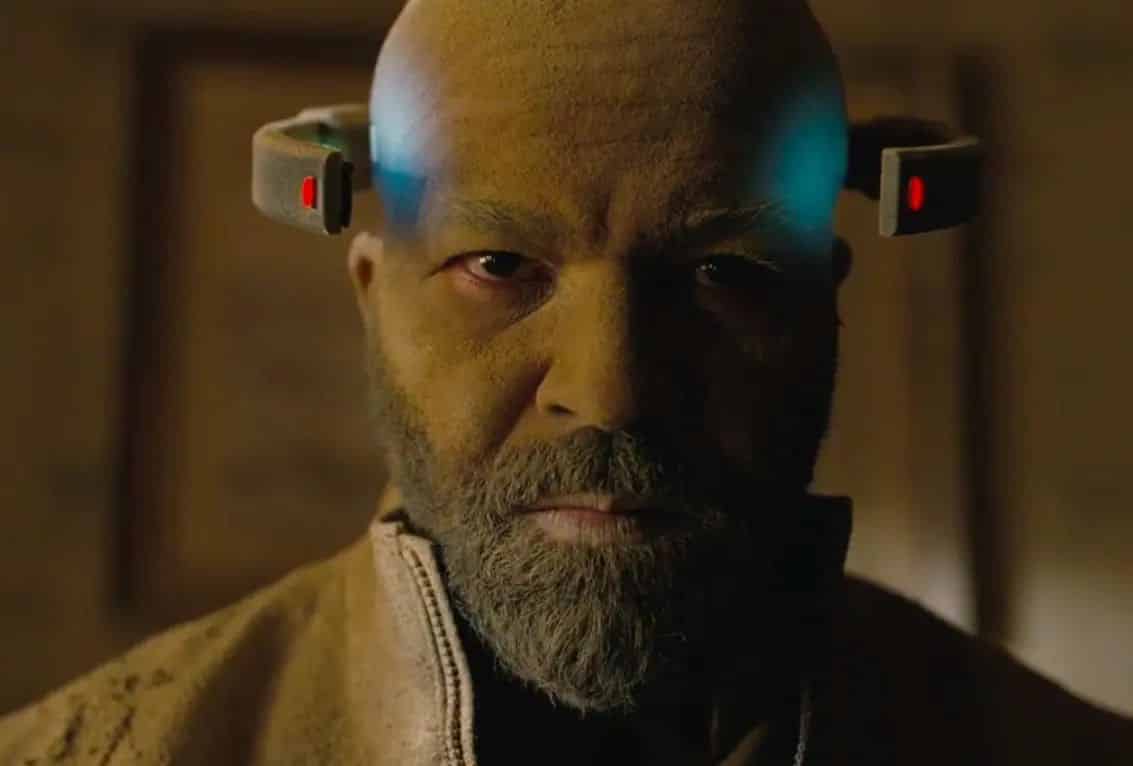

Caleb discovers that Charlotte has been doing her own “behavior training” on human beings, as humans once did on the hosts. When Caleb describes the infected humans as “carriers,” Charlotte corrects him, “I prefer the term ‘host.’” William (Ed Harris) chides Maeve (Thandiwe Newton), “There is no us anymore. There’s just you.” This is a bold and interesting idea, the blurring of boundaries and the breaking down of barriers. There is no “us” or “them;” there is no “in” or “out.” There just is.

In “Generation Loss,” the fourth season of Westworld grapples with the idea of imposing a narrative upon reality, of bending the outside world to the logic of stories. Christina wakes up in her apartment to realize that she has drawn a mysterious tower into otherwise idyllic paintings of Manhattan, as if that construct is some monstrous and Lovecraftian concept trying to manifest itself. It is something unreal that is being made real, a nightmare given form.

With these reveals, Christina’s confrontation with Peter (Aaron Stanford) in the season premiere makes a great deal more sense. Peter claimed that he was a character trapped in one of Christina’s stories. With the reveal that Christina lives in the world that Charlotte conquered, it seems as if Christina has been tasked (unconsciously) with constructing narratives to trap the city’s human inhabitants, serving a function similar to that played by Sizemore during the first season.

This is Westworld being even more abstract than usual. The theme parks in the earlier seasons were all built around narratives. As much as they were nominally built around historical eras, in reality they existed to further historical myths. The eponymous theme park captured the story of the Old West, not its reality. It was just as much a fantasy as the Games of Thrones-themed world implied in the third season. It has as much relationship to reality as “Main Street, U.S.A.” in Disneyland.

In Simulacra and Simulations, philosopher Jean Baudrillard argued that Disneyland’s hyperreality was “presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyperreal and of simulation.” To Baudrillard, the imaginary quality of Disneyland was a distraction, one designed to conceal a deeper and more unsettling truth: The world outside of Disneyland was just as unreal.

Maeve and Caleb flee from the park to a construction zone identified as a “Park Expansion Project — Active Demolition Site.” Caleb’s coordinates suggest that this confrontation takes place in California. The real west is being demolished and a fantasy built atop it. Appropriately, the site is just north of Big Sky Movie Ranch, the source of various iconic depictions of the Old West in American pop culture, from Rawhide and Gunsmoke to Little House on the Prairie.

In “Generation Loss,” it becomes clear that fiction is colonizing reality. It is telling that the episode repeatedly describes Charlotte’s brainwashing technology as a “parasite.” It recalls the opening scene of Inception, a film written by showrunner Jonathan Nolan’s brother Christopher. In that scene, Dominick Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) explains that “the most resilient parasite” is “an idea.” It is notable that, once infected, Caleb is controlled via a broadcast, a signal and a sound.

“At a certain age, your brains become more rigid, difficult to change,” Charlotte explains to Caleb. “Fortunately, that’s not the case with children.” She continues, “With them it was seamless, a parasite growing in perfect symbiosis with their minds. It took a generation for those children to mature, for me to gain complete control over your world.” In short, Charlotte’s evil plan for world domination lies in brainwashing children, in warping and shaping their minds.

Westworld understands that narratives and stories are an important way of implementing such a system of control. It often doesn’t matter what is actually real; it simply matters which stories people internalize. “That’s the thing about this world,” Christina’s date reflects over drinks. “Some of the most unbelievable things turn out to be true, and the things that feel the most real are nothing but stories that we tell ourselves.”

Much of the fourth season of Westworld has drawn from the iconography of the 1930s and is haunted by the specter of the industrialization of human suffering that waits over the horizon. However, “Generation Loss” suggests that the season is built around another realization of that era — the observation often attributed to Joseph Goebbels, “Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth.” In “Generation Loss,” Westworld suggests that entire worlds can be built on such lies.

This is a common recurring theme in Jonathan Nolan’s work. His short story Memento focused on a man with the inability to create long-term memories, who compensated by constructing a narrative that gave his world meaning. His screenplay for The Prestige imagined two dueling magicians trying to trap one another within their own narratives. His work on The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises concerns the stories that societies tell themselves to function.

The final shot of “Generation Loss” features a pan across the southern bay of Manhattan, revealing that ominous broadcast tower standing where the Statue of Liberty should be. The Statue of Liberty represented its own aspirational narrative of what America could be, of a nation that was a beacon to the world and a welcoming home for outsiders. The tower is much more ominous, seeming more like a trap to keep those caught within its broadcast range.

“Generation Loss” suggests that maybe societies should be careful of the stories that they tell themselves, because those stories can occasionally become reality.