The summer of 2012 was a big moment in the history of blockbuster cinema. The previous year had demonstrated that superheroes were a permanent feature of the blockbuster landscape, even superheroes with no name recognition or from smaller publishers. Movies like Green Lantern, Thor, Captain America: The First Avenger, and The Green Hornet were built around properties that were at the time seen as secondary at best. In contrast, the big names dominated the following summer.

The big battle of 2012 was fought between Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises and Joss Whedon’s The Avengers. In many ways, it was a restaging of the box office showdown between The Dark Knight and Iron Man four years earlier. The Dark Knight Rises was an elegiac conclusion to a sprawling auteur-driven trilogy, while The Avengers was just the starting pistol on the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The two films finished in the top two positions at the domestic box office.

However, there was a somewhat smaller blockbuster that summer. It would end up being quietly revolutionary in its own way. The Amazing Spider-Man is not a particularly good film. It certainly isn’t a defining cinematic adaptation of its title character. Its reviews were solid rather than exceptional. It earned a respectable $757M at the global box office, which was less than Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 3 five years earlier or any of Jon Watts’ three solo Spider-Man movies that would follow.

In fan circles, the Amazing Spider-Man movies were largely seen as films in need of redemption. In broader culture, they are perhaps most notable for providing raw material that Spider-Man: No Way Home could repurpose into nostalgia. However, The Amazing Spider-Man also sent a signal out into Hollywood. It quietly provided a useful template for studios in terms of how these major franchises could be more efficiently managed and exploited.

The Amazing Spider-Man demonstrated the speed at which audiences would accept a hard reboot of a successful and beloved property. There have always been reboots of classic properties. Given the amounts of money involved, Hollywood is a naturally conservative industry. If something worked before, why not just do it again? If something offered an impressive return on investment, why not just pump even more money into doing the same thing for an even bigger return?

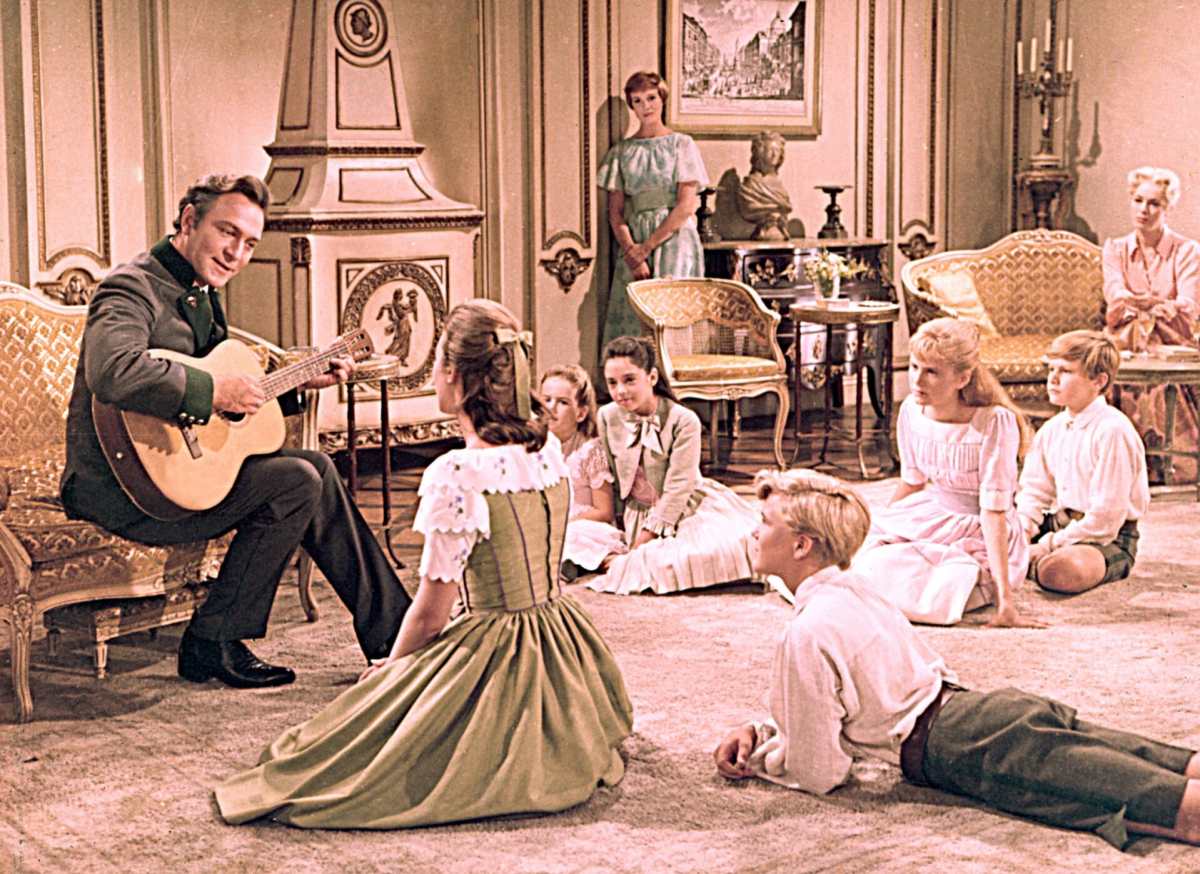

Historically, the assumption had been that audiences would want to see something like what they already loved. After Cleopatra nearly bankrupted 20th Century Fox in the early 1960s, the studio struck gold with The Sound of Music in 1965, which became the second highest-grossing movie of all time behind Gone with the Wind. Because sequels were largely seen as something gauche at that time, the studio’s attempts to capitalize on that success led to attempts to emulate The Sound of Music.

Not content with having lucked into profitability, the studio doubled down and produced a string of absurdly expensive musical flops chasing the success of The Sound of Music: Doctor Doolittle in 1967, Star! in 1968, and Hello, Dolly! in 1969. In June 1966, prompted by the success of The Sound of Music, the studio posted $20.2M pre-tax profits. By 1970, after this string of big-budget disappointments, the studio posted losses of $77.3M. This speaks to Hollywood’s enthusiasm to chase a trend.

During the 1970s, as sequels became more respectable, it became more acceptable for the major studios to remake and reboot existing films. In 1976, Dino De Laurentiis pushed a remake of King Kong through an extremely troubled production. In 1977, Oscar winner William Friedkin followed up box office success of The Exorcist with Sorcerer, a remake of French classic The Wages of Fear. However, the label itself remained contentious. To this day, Friedkin doesn’t “consider it a remake.”

As Hollywood’s model pushed more films to become franchises, revisiting an existing and popular property became an increasingly complicated proposition. Making a newer version of an existing film could be described as a simple remake, but there needed to be a word that could be used for the act of restarting an entire franchise — for remaking a movie that had sequels and spin-offs, in the hopes that the remake itself could support sequels and spin-offs.

The term “reboot” to refer to the restarting of existing intellectual properties took root in 1990s comic book culture, with the first recorded use of the term in the context coming from a Usenet comic book discussion in 1994. In 2005, David S. Goyer was still explaining Batman Begins as “the cinematic equivalent of a reboot,” with his use of the word “equivalent” illustrating that the word wasn’t yet part of the movie-making vernacular. Things would change very quickly.

The Amazing Spider-Man was far from the first cinema reboot. However, these reboots tended to be spaced far apart. Following Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, Warner Bros. would wait until the mid-1990s before making any serious attempt to revive the property with Superman Lives. When Batman & Robin underwhelmed in 1997, the studio put the franchise on ice for eight years before allowing Christopher Nolan to put his own stamp on the Caped Crusader in Batman Begins.

In the years leading up to The Amazing Spider-Man, there were a couple of quasi-reboots that came thick and fast. After the box office disappointment of Die Another Day, Casino Royale went back to basics and offered an origin story for James Bond (Daniel Craig). However, the Bond franchise was also very much its own animal, tending to opt for soft resets between each of the various lead actors. In fact, Casino Royale even carries over cast member Judi Dench from Die Another Die.

There is also a case to be made for The Incredible Hulk, which was released only five years after the critical and commercial disappointment of Ang Lee’s Hulk. However, there was a sense that Marvel needed to be defensive about the decision to revisit the property. “It felt silly to wait more than five years to bring The Hulk back to the screen,” justified producer Kevin Feige. Indeed, while The Incredible Hulk is clearly a reboot in hindsight, it was much more ambiguous at the time.

The film was announced as “a sequel.” The change in creative talent was perhaps more analogous to the transition from Batman Returns to Batman Forever than from Batman & Robin to Batman Begins. As Christopher Orr noted in his review, The Incredible Hulk is “not a sequel to Ang Lee’s 2003 Hulk, but it could easily be mistaken for one.” The former begins with Banner (Edward Norton) hiding in South America, seeming to pick up from where Banner (Eric Bana) was at the end of the latter.

In contrast, The Amazing Spider-Man was a clean break from what came before. It arrived just five years after the previous entry in the film franchise. Spider-Man 3 had been a massive commercial success. It was the highest-grossing movie of the domestic box office in 2007, not a commercial disappointment like Hulk, Star Trek: Nemesis, or Batman & Robin. It also wasn’t a critical embarrassment like Die Another Day, earning tentatively positive reviews.

Still, there was no ambiguity about the relationship between Marc Webb’s The Amazing Spider-Man and Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 3. The film even replayed the title character’s origin story, to much derision from critics. This was a do-over. It was a restart. It was a new version of this character and this franchise, constructed entirely from scratch. As such, it gave the production team the opportunity to replay the hits by recycling old characters and plots.

The Amazing Spider-Man was not a success on par with The Avengers or The Dark Knight Rises, but its critical and commercial performance reassured studios that audiences wouldn’t punish brazen reboots and remakes of beloved properties. Studios need not let profitable properties lie fallow. The franchise factory farm could keep churning out content, with no upper limit. A successful film could launch sequels and spin-offs, and then it could immediately restart when the talent grows tired.

The trend has only accelerated in the years since The Amazing Spider-Man. Less than four years after Christian Bale took off the cowl in The Dark Knight Rises, Ben Affleck would put it on in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Only two years after the commercial underperformance of The Amazing Spider-Man 2 seemed to close the book on Andrew Garfield’s web-slinging wonder, Tom Holland donned the spandex in Captain America: Civil War.

The timeline has become so compressed that sometimes one era isn’t even over before the next begins. Robert Pattinson headlined The Batman in 2022, with Ben Affleck and Michael Keaton also playing the Caped Crusader in The Flash. There is some speculation that the upcoming Avengers: Secret Wars might lead to an in-continuity soft reboot of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, effectively a restart built into the densest deluge of content in the studio’s history.

The Amazing Spider-Man is often overlooked in assessing the superhero blockbusters of 2012. It is certainly a weaker and less impressive film than either The Avengers or The Dark Knight Rises. However, for better or worse, it casts a long shadow. Its influence is still being felt today. Hollywood has spent a decade doing whatever a Spider-Man franchise can to keep churning out content.