Media permanence is a relatively modern phenomenon, but it is one that we take for granted. Recent events at Warner Bros. involving HBO Max demonstrate that, in the streaming age, media is as impermanent as ever.

In the modern world, most viewers assume that a given film or television show from a major studio will always exist and will always be accessible. After all, these projects cost money and so have an intrinsic value to their owners. In a world where the internet has made communication faster and easier than ever, everything should be accessible. In some cases, it is. A Disney+ subscription will give viewers access to decades of episodes of The Simpsons.

However, it wasn’t always this way. In their early days, film and television were treated as ephemeral and disposable media. They had a limited shelf life, and the idea that audiences might want to watch something from last month, let alone last year, seemed inherently absurd. There was no sense that these mediums had a future. In 2013, the Library of Congress announced that three-quarters of all silent films had been lost.

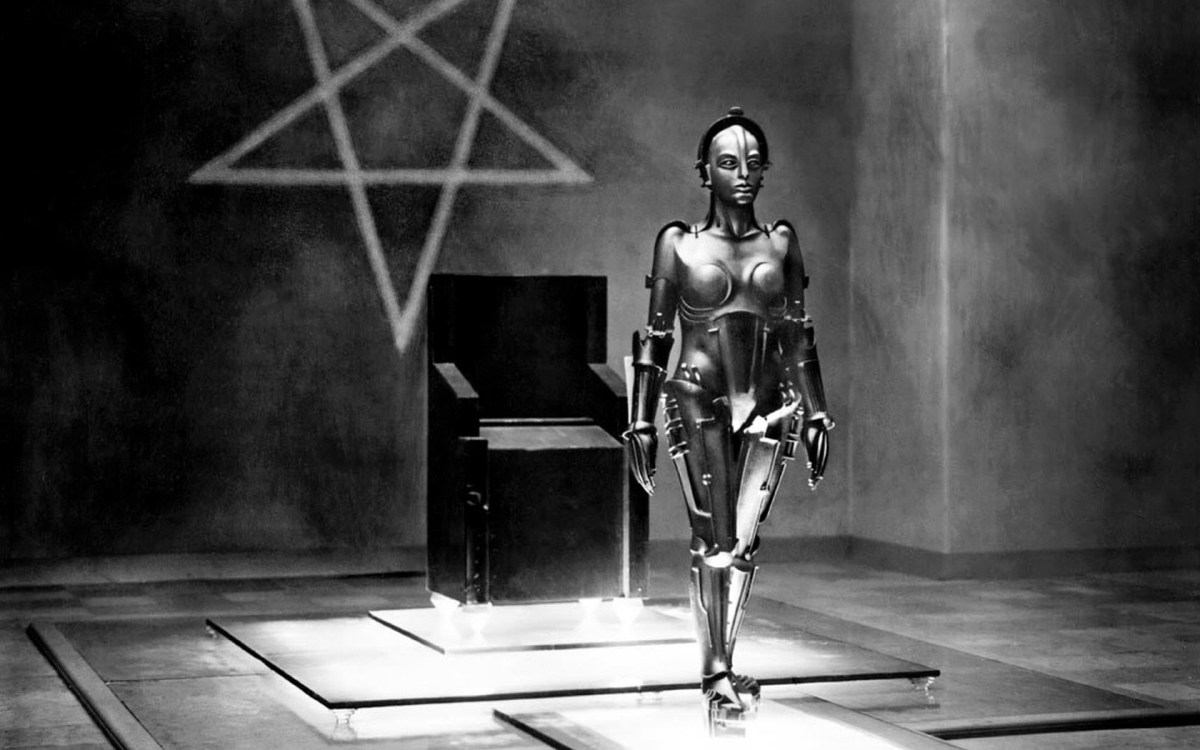

It is tempting to assume that these losses, while tragic, were largely confined to unpopular or unacclaimed works, that the “important” films of the silent era were preserved. Setting aside how this argument assumes that the “worth” of a work could be reliably determined on initial release, it is clearly not the case. Missing scenes from Fritz Lang’s masterpiece Metropolis were only recovered in 2008. Alfred Hitchcock’s The Mountain Eagle is still missing.

Of course, even those films that weren’t lost had to be maintained and preserved. Film stock is very delicate, and it requires considerable effort to protect the image over years and decades. This issue only really came to the forefront due to concerns raised by the “Movie Brat” directors like Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg. These were, after all, among the first wave of filmmakers to grow up thinking of film as an artform. It makes sense that they would be concerned about its permanence.

Doing press for Raging Bull in 1981, Scorsese lamented how his previous film New York, New York looked “terrible” only four years after release. In 1998, Spielberg wrote to Warners to request “a thorough check” of its archive after watching a poorly maintained print of Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Scorsese has become a passionate advocate for film preservation and restoration, fighting to minimize the possibility of the medium’s history being lost or erased.

Early television had similar issues. Even more than film, television was treated as an ephemeral medium. Much early television was broadcast live, and the medium was often treated as something closer to theater than to film. The importance of commercial advertising to the medium contributed to the sense that the actual content of a given broadcast was incidental. This was a medium that Newton Minow famously described in 1961 as “a vast wasteland.”

During the early 1970s, the DuMont Television Network was being bought by another company. There were arguments about how best to deal with the network’s extensive library. According to actress Edie Adams, one of the lawyers promised to “take care of it” in a “fair manner.” He did this by arranging to have the library loaded into three trucks, the trucks loaded onto a barge in New Jersey, and their contents dumped into Upper New York Bay.

Again, the assumption might be that the “important” shows survived these sorts of purges. Once again, ignoring the survivor bias at play, there are plenty of counter examples. Doctor Who is a show successful enough that Disney snatched up international distribution rights. However, many of its early episodes were purged from the BBC archive to clear storage space and reuse recording tape. Episode hunters are still scouring the globe, hoping to find lost recordings in distant countries.

In recent years, it became tempting to assume that these problems were cautionary tales from a bygone era. After all, the emergence of home media and then streaming made media much more accessible to viewers. The advent of the DVD box set meant that audiences were no longer subject to the whims of broadcast schedules and no longer had to chase old favorites through the local listings. Digital media made it easier to store larger quantities of data in smaller physical spaces.

Of course, the digital age came with its own unique set of challenges. A 2007 study suggested that the annual cost of storing a 4K digital master of a film was over 12 times more expensive than preserving a film reel. It is also easier to remove access to media that is available to viewers over streaming. This doesn’t even have to happen intentionally, as Disney demonstrated when it accidentally “censored” an episode of The Falcon and the Winter Soldier back in April.

Since taking control of Warner Bros., David Zaslav has demonstrated how impermanent most modern media truly is. Seeking to take advantage of tax write-offs, Zaslav famously canned a number of projects that were reportedly close to completion, most notably Batgirl. Zaslav has overseen a dramatic culling at the company’s animation division. Zaslav is trying desperately to manage the company’s $49 billion of net debt, and that means cutting costs wherever possible.

It is hard to overstate just how desperate things appear at Warner Bros. Zaslav’s top priority is to get cash flowing again. Hollywood Reporter journalist Borys Kit suggested the studio only had enough money to release two films theatrically in the final third of the year. This strategy involves the removal of content from the company’s streaming service, HBO Max, including both library titles and original programming created specifically for the service.

The removal is driven by a number of different motivating factors. Most obviously, the company hopes to more effectively monetize previously exclusive titles like Robert Zemeckis’ The Witches or Brandon Trost’s An American Pickle. Those films were originally made available to HBO Max subscribers at no additional cost. They have since been removed from the service and made available on streaming video-on-demand services like VUDU or the Microsoft Store.

The assumption is that the number of customers who subscribed to HBO Max specifically for titles like Moonshot and Superintelligence is statistically insignificant; few signed up specifically to watch them, and fewer still will unsubscribe specifically because they were removed. Their immediate value to the streaming service is, by this metric, negligible. However, removing these titles and making them available to rent or buy monetizes them, bringing income into Warner immediately.

Of course, the counterpoint to this is that such removals represent an existential crisis to the streaming model. They demonstrate to viewers that the services these providers offer can disappear with little or no warning, which will erode customers’ faith in the larger brand. However, this is most likely a gradual and even cumulative consequence, if it happens at all, and is harder to quantify than the monthly income that a given title generates in rentals or purchases.

The goal of removing a lot of film and television from HBO Max, even content designed specifically for the service, is that it can be monetized elsewhere. This may involve selling it directly to consumers, whether digitally or physically. It may also involve licensing it to another streaming service willing to pay a fee to Warner Bros. to host it as part of its library. This sort of deal hinges on exclusivity, as nobody will buy something that can be easily watched elsewhere cheaper.

There are two other significant reasons to remove content from HBO Max, and these are not built around making that content available through other channels. The first is “to receive a tax benefit on the write-downs” as a way of cutting the accrued losses. This was the business logic that Zaslav was using when he canceled Batgirl, and it reportedly applies here. Such write-offs cannot be monetized again without having to pay the money back.

The second reason is similarly cynical. Warner Bros. is reportedly shelving these projects to avoid paying royalties to cast and crew. Of course, streaming royalties are very different from the established payment structure for television and often have to be negotiated separately, but they still exist. Earlier this year, the Writers’ Guild of America won a case against Netflix over streaming residuals, and there is the looming prospect of the major unions striking over the issue in 2023.

In this case, simply not making the shows available to stream saves Warner Bros. money, even if there is no other streaming service interested in footing the bill. While high-profile titles like Westworld are dominating press coverage of these removals, those more recognizable titles seem certain enough to survive. After all, Westworld is the rare modern television show to still receive a physical media release, ensuring that its episodes will survive in some form in the wider world.

At the time of publication, there are several titles that are simply not available anywhere since their removal from HBO Max: About Last Night, Aquaman: King of Atlantis, Ellen’s Next Great Designer, Generation Hustle, Genera+ion, My Mom, Your Dad, Odo, Ravi Patel’s Pursuit of Happiness, The Runaway Bunny, and Theodosia. There are likely plenty of others. What if no streaming service wants them? Even just taking up space on the Warner Bros. servers, these shows are a cost on the balance sheet.

As media pivoted into the digital age, there was always the question of what would happen to movies and television shows produced by media companies that had never received a physical release — no film reels, no cassettes, no discs — in the event that those companies collapsed. Given what is happening at HBO Max, the answer might arrive sooner than expected.