Much has been written about the death of the conventional old-fashioned movie star, with many writers pointing to actors like Tom Cruise or Leonardo DiCaprio as the last examples of a dying breed.

There are a number of reasons for this. Most obviously, Hollywood has largely stopped making the kind of star-driven blockbusters that produce and maintain movie stars. In modern Hollywood, the intellectual property is the star, and the performer can feel incidental. Audiences will turn out in droves to see Chris Evans as Captain America or Chris Hemsworth as Thor, but they will ignore their star-driven projects like Gifted or Blackhat. As such, the star-making machine no longer exists.

That said, there is also a sense that many modern performers don’t actually want to be movie stars, that this sort of stardom is not an ideal towards which they strive. Colin Farrell is perhaps the most obvious example of this, a handsome and charismatic leading man who emerged at the turn of the millennium in a number of high-profile crowd-pleasing spectacles, but who seems to have only recently found the niche that makes him comfortable.

It can be hard to quantify what exactly makes a movie star, but Colin Farrell certainly has “it.” He’s an individual who can light up a room just by stepping into it, as demonstrated by his recent awards season run. Farrell is the kind of guy who will pause on his way to collect an award at the Venice Film Festival to shake hands with a collaborator that he recognizes and who will take time out of his Golden Globes acceptance speech to acknowledge his co-star, Jenny the Donkey.

Hollywood knew that it had something with Farrell, and the industry seemed to clear a path for the young actor to stardom. He was signed to the same talent agency as Donald Sutherland, Ed Harris, and Cuba Gooding Jr. As early as September 2001, industry observers were predicting that the same “pipeline” that had made Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie movie stars would turn Farrell into a household name. Not bad for a young man who had dreamt of being a footballer rather than an actor.

Farrell’s early career was everything that an emerging star could hope for. He popped in director Joel Schumacher’s Tigerland, and Schumacher turned to him to take over the lead in Phone Booth after Jim Carrey dropped out. Steven Spielberg selected him for a choice supporting role in the science fiction film noir Minority Report, which found the Dubliner playing opposite Tom Cruise. Farrell went from starring in the BBC soap opera Ballykissangel to Minority Report in the space of four years.

Indeed, it’s to Farrell’s credit that many of these early roles still stand up to rewatches. Revisiting movies like Tigerland, Minority Report, and Phone Booth, Farrell’s ascent to the top of the A-list seems all but assured. However, Farrell was not as lucky in the years that followed, as Hollywood tried to shape the young actor into a conventional leading man who could anchor more conventional blockbuster fare.

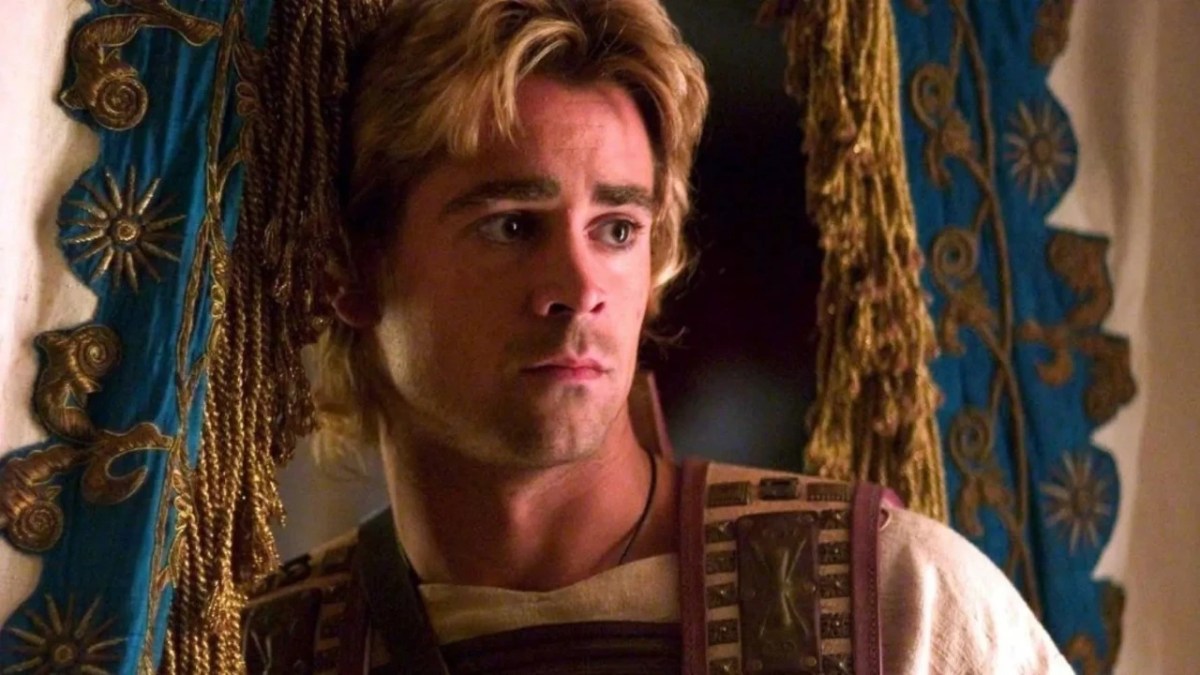

In the years after Minority Report and Phone Booth, Colin Farrell split his time between smaller Irish-set projects like Schumacher’s Veronica Guerin or John Crowley’s Intermission and more traditional big-budget films like The Recruit, Daredevil, S.W.A.T., and Alexander. These were all choices from the star-making playbook, pairing the up-and-comer with veteran performers like Al Pacino and Samuel L. Jackson, big-name directors like Oliver Stone, and tying into the nascent comic book movie boom.

During this time, Farrell became a full-blown celebrity. He was the subject of much industry gossip and even had a sex tape leak. By the time that Alexander was released in cinemas, press coverage contended that Farrell’s “tabloid headlines (had) thus far outshone the impression he (had) made on moviegoers.” Farrell has talked about how damaging the negative reviews of Alexander were for him, while also conceding with hindsight, “I was due a kick in the arse. I really, really was.”

Farrell’s next couple of years were tough. He struggled with drug and alcohol addiction. He’s admitted that he has no memory of shooting Michael Mann’s Miami Vice. “I’ve seen bits of it since and I just stare blankly at them,” he’d confess years later. “I don’t remember any of it.” Ironically, he does vividly remember Charlie Rose’s inability to recall the movie’s name. Farrell doesn’t talk fondly about Miami Vice, critiquing it as “style over substance.”

Of course, Farrell’s involvement with Miami Vice came at a troubled time in his life. “I just completely fell to shit on that one,” he’d later admit. “It was literally the first time I couldn’t say to anyone around me, ‘Have I been late for work, have I missed a day’s work, have I been hitting my marks?’ Because the answer would have been yes, yes and no.” Farrell would check himself into rehab almost immediately after the shoot wrapped. The movie seems to represent a turning point for the actor.

Rewatched at a distance from the hype around it, Farrell’s performance in Miami Vice is a harbinger of things to come. With his scruffy mullet and handlebar moustache, Farrell’s Sonny Crockett feels like one of the most handsome men alive trying desperately to shed his movie matinee good looks. Of course, Crockett is still a very good-looking man, but there’s a sense of vulnerability and uncertainty to the character that had been missing from Farrell’s other blockbuster work.

In the years following Miami Vice, Farrell retreated from Hollywood movie stardom. He worked on low-budget auteur projects like Woody Allen’s Cassandra’s Dream, Martin McDonagh’s In Bruges, or Neil Jordan’s Ondine. He wasn’t afraid to take lower-key supporting roles, playing opposite Jeff Bridges in Crazy Heart, filling in for the dearly departed Heath Ledger in The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, or joining the ensemble in Peter Weir’s The Way Back.

These were not choices that movie stars made. Against all odds, Colin Farrell seemed to be allowing himself to have fun again. 2011 was a watershed year for Farrell, with the combination of a scene-stealing turn as a sexy vampire in the underrated horror remake Fright Night and a heavily made-up supporting role in the comedy Horrible Bosses that gave the actor a pot belly and a combover. Farrell was an actor willing to play with his movie star good looks, to subvert and deconstruct them.

Reuniting Farrell with Miami Vice co-star Jamie Foxx, Horrible Bosses is a strangely important movie in Farrell’s filmography. It marked the point at which the actor discovered the pleasures of playing performing under prosthetics, allowing him to shed the handsomeness that defined so much of his early career. Many actors resent work under prosthetics, finding their application time-consuming and their use restrictive. Instead, Farrell seems to find these sorts of performances liberating.

Farrell has talked about this. Undergoing a physical transformation to play Henry Drax in the television series The North Water, Farrell explained, “I couldn’t really step away from the character. I couldn’t get out of the costume, he was always with me. It was a great benefit to me because it just meant 24 hours a day, seven days a week for however many weeks we shot, I was constantly inhabiting this physical space that was very different for me.”

Farrell so enjoyed playing the Penguin in The Batman that he lobbied for a spinoff. “The only thing I had an idea was that I wasn’t nearly getting to explore the character as much as I wanted to,” he stated. “Because there was all this extraordinary work done by [makeup artists] Mike Marino and Mike Fontaine and his team, and I just thought it was the tip of the iceberg, pardon the pun, that we were getting to do the six or seven scenes that we did in the film. I was grateful for them, but I wanted more.”

A lot of Farrell’s later roles play with his movie star charisma. He can weaponize it in movies like Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled but can also push it into the uncanny with his performances in Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Lobster and The Killing of a Sacred Deer. Even in Tim Burton’s Dumbo, a relatively conventional blockbuster, Farrell plays with his physicality when cast as an amputee. Even in recent films where the actor doesn’t wear prosthetics, like Guy Ritchie’s The Gentlemen, Farrell is giving a character-actor performance.

Colin Farrell is arguably part of a larger trend among his generation of performers. Jon Hamm might be the most obvious example, an absurdly handsome star of prestige television who looks like “a cartoon pilot” but whose post-Mad Men career has largely consisted of indulging his comedy nerdery with roles in movies like Absolutely Fabulous, Bridesmaids, and Between Two Ferns, while also subverting his handsomeness by playing sleazy roles in movies like Baby Driver, The Town, or Richard Jewell.

Farrell is emblematic of a generation of performers who feel like character actors who found themselves trapped in the bodies of leading men. There are plenty of other examples, from James Franco’s obvious exhaustion at efforts to make him a conventional movie star in Oz the Great and Powerful when he’d much rather be making The Disaster Artist, to the pleasure that Chris Hemsworth takes playing goofy comedy in Ghostbusters and unsettling smarm in Spiderhead.

It has been a long and challenging road for Colin Farrell as a performer, finding a space in which he feels comfortable and which plays to his unique strengths. It’s easy to understand how Hollywood looked at this very handsome and charismatic leading man and decided to manufacture an old-fashioned movie star. Ultimately, Farrell’s body of work speaks to something much more interesting and compelling, an actor who seems more curious about his star power than excited by it.

In 2022, Colin Farrell appeared in major roles in After Yang, The Batman, Thirteen Lives, and The Banshees of Inisherin. That’s a very diverse set of performances in a very diverse set of films, demonstrating a flexibility that would be impossible for a more conventional movie star. It seems like Farrell is exactly where he wants to be.