Gone Home wasn’t the first walking simulator — that honor is sometimes bestowed upon Dear Esther and sometimes upon the much older Myst — but it is the quintessential one. It took the learnings of those precursors and mixed them with a more pronounced awareness of mise-en-scène and a laser focus on telling a personal story. The result is a game that moved the needle on what games can be, spawned a parade of imitators and occasional successors, and inspired derision. Ten years on, Gone Home has as divisive a legacy as any game, reviled almost as widely as it is respected.

I fall on the latter side of that division. I remember I first played it a few months after release at a colleague’s prompting. I played it on a severely underpowered laptop, the experience marked by muddy textures, a juddery frame rate, audio cut-outs, and at least one crash. Marked, but unmarred. Despite the issues, I was entranced. Yes because of the main narrative and the unparalleled environmental storytelling, but also because of the backdrop. Gone Home is deliciously atmospheric

A large part of that stems from it feeling like a horror story. The game’s 1995 was retro at release; now it’s quaint — a callback to a less online, more tangible time. That vibe underscores the opening, with a voicemail left on an answering machine: a daughter telling her family she’ll arrive home from an overseas trip sometime after midnight on June 6. But there’s no mobile phones, no internet, no immediately and perpetually accessible means of communication… It’s the perfect setup for a chilling tale:

“It was a dark and stormy night when Katie Greenbriar arrived on the doorstep to her family’s new home after a year abroad. Rain thrummed against the roof, occasionally punctuated by the heavy grizzle of thunder. She had expected a warm homecoming, greeted by the smiles of her parents and sister. Instead, the windows were dark, the entry hall cold and still. She swung open the door into darkness, into silence, into…”

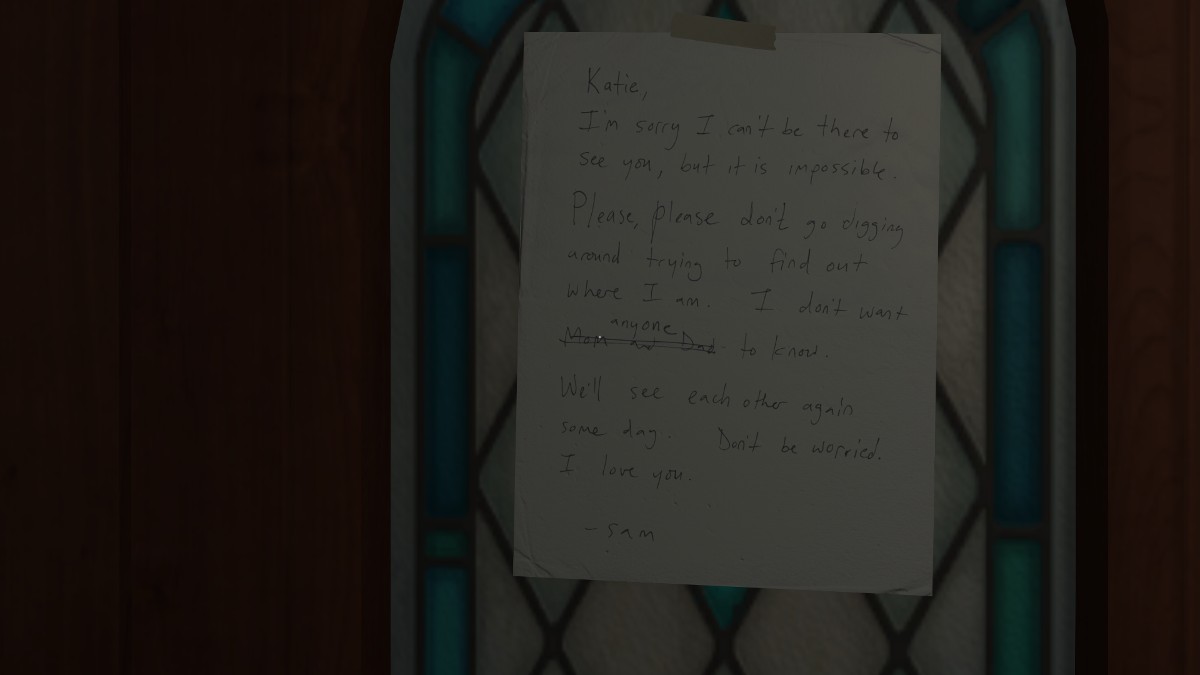

What remains one of the most intimate stories in all of gaming. That hint of menace never blossoms, at least not if what you expect is a teen slasher flick. Instead, Katie moves slowly through the sprawling house, unpicking the secrets of her family. Most of what we’re told through audio logs is about Katie’s younger sister, Sam, and her struggles to fit in, to be accepted. First, it’s at her new school; later when she discovers her lesbian identity, it’s by her own parents. It’s a story of self-discovery, of punk attitudes, and burgeoning relationships played out against a backdrop of intolerance. That latter fact is never overt. Sam is given limits, but it’s not as if the Greenbriar parents lock her up and force her into conversion therapy. Nevertheless, despite the lack of domestic horror, the psychological terror, that persistent sense of not-quite-rightness — reinforced through notes from Sam to not tell their parents what she finds — is no less impactful. It’s what makes your first sight of the red-stained bathtub so shocking.

But Gone Home is so much more than Sam’s story thanks to the house. Environmental storytelling had been done before. Blood spatters and graffiti on walls, skeletons arranged in compromising positions, set dressing to let you know that something horrible had happened. It was already on the rise through the seventh generation of consoles. But it tended to be either happenstance or alluding to bigger concerns. Gone Home focuses that on the personal.

The game uses the items of a house to let you in to the personal lives of the Greenbriar family. Letters, adornments, pamphlets, stacks of books… They tell you that Katie’s father is a failed fiction writer, now turned his talents to work that brings him no joy, while his chosen career is the object of scorn to his extended family. They tell you that the relationship between Terrence and Jan Greenbriar is rocky, possibly problematized further by infidelity. They tell you of betrayal, of lies, of fears, of secrets kept and buried in the basement. These incidental items provide one revelation after another, but only if you actively look for them and, importantly, look at them. You have to be involved to get the story, and that’s what makes Gone Home such a great game.

A fascinating comparison is The Last of Us, released just a few months after Gone Home. It, too, was lauded for its storytelling, acclaimed as an example of what ludonarratives can offer. It’s telling because, a decade later, The Last of Us is also a celebrated TV series and Gone Home is not. Naughty Dog’s version and HBO’s version of Joel and Ellie’s post-apocalyptic journey differ, but it’s still a story that translates smoothly across mediums because it was always a filmic production. Not so with Gone Home. It’s not that it could only be a video game — the idea that anything is unadaptable is a fallacy — but it works best as an ergodic story, one that you have to work through and work for.

But that wasn’t enough for some. The term “walking simulator,” though since widely embraced, began as a pejorative. It was a way of saying that this thing is not a game. All you do is walk and listen to a voice tell you a story. The entire experience is spoonfed, leaving the player with no agency. There’s no real sense of challenge. There’s no fail state. The atmosphere doesn’t ultimately serve the story because it’s not horror in the traditional sense. And, then, even if it is a game, the problem is the saccharine, painfully “white middle-class” story with no real twists to speak of beyond the oh-so-transgressive queer love story. In sum: Gone Home is boring. What’s worse is that the positive reception validated a whole class of “not-games.”

To some degree, those claims are justified; they’re all true, after all. But it’s important to recognize that Gone Home is the sum of those parts. The magic lies within the way it all works together. Ludonarrative dissonance was a big analytical talking point ten years ago. Gone Home resolves that, being a shining example of ludonarrative unity that has rarely been topped: Katie is a voyeur in this sprawling mansion because the family moved into it while she was overseas. She’s stumbling into it, as unfamiliar and uncertain as the player, as creeped out as the player because she doesn’t know that the lights flicker because of faulty wiring, and Sam’s casual allusions to it being a murder house don’t help. It’s atmospheric and chilling because that situation would be. It’s absent of twists and challenges because they wouldn’t make sense in a narrative that aims for verisimilitude. It simply is a work of art that knows where its borders are.

While the flurry of walking simulators and not-games has faded over the past ten years, Gone Home has left an indelible mark on the industry. Would the Night City of Cyberpunk 2077 have felt so lived in without it? Would Watch Dogs: Legion’s best mission exist in its current form without it? Would Elden Ring have felt so textured? Perhaps, but I have my doubts. Gone Home was a game that, more than any other, made a statement that games can be intensely personal things. And that genie should never go back in the bottle.