Even before a single image appears on screen, Saw III begins with a promise. “Game over,” boasts Amanda (Shawnee Smith), dialogue sampled from the climax of Saw II. Then Detective Eric Matthews (Donnie Wahlberg) screams, “I’ll fucking kill you!” It certainly sets a tone for the movie that follows.

In many long-running film series, especially horror franchises, there comes a point where – consciously or otherwise – the films seem to scream, “Enough!” Often, entries seem couched in a contempt for both the films themselves and for the audience eagerly consuming them. Such entries tend to arrive around the third installment of a given series; the point at which the series is no longer just the original and a sequel, but instead threatens to become a brand unto itself.

Halloween III: Season of the Witch, the last in the original run of films to involve franchise creator John Carpenter, ends with lead actor Tom Atkins trying to avert an apocalyptic advertisement following a broadcast of Halloween. He stares down the camera, screaming at the audience, “Turn it off!” Alien 3, one of the most bleakly nihilistic franchise films ever made, can be read as a metaphor for the self-perpetuating horror of the Alien film series.

The Saw franchise is interesting. For seven years, like clockwork, the series churned out a new film for Halloween. The poster for Saw IV promised, “If it’s Halloween, it must be Saw.” The franchise has grossed over a billion dollars at the global box office, which is not bad for a combined budget of under $100 million. Before The Hunger Games and John Wick, Saw was the flagship franchise for Lionsgate, just as the A Nightmare on Elm Street series had been for New Line Cinema in the 1980s.

However, the legacy of the franchise is somewhat contested. Contemporary press coverage often dismissed the series as “torture porn.” This is interesting, because the original Saw isn’t actually that violent. Very little gore is shown on screen. While it’s certainly nastier than some of director James Wan’s subsequent work in the genre, like Insidious or The Conjuring, it’s not graphic for the sake of being graphic. The sequels, however, are a different story.

Wan has discussed his relationship with the franchise and what it became after the original film. “I definitely feel like in a lot of ways Saw did so many great things for me, but it put me into this category that I don’t really see myself in,” he told IndieWire in March 2011. “I don’t want to be known as the king of gore. And here’s the irony, the first one isn’t that gory, it’s more psychological. People forget that. People have retroactively given me this reputation based on the whole franchise.”

Despite transitioning to mainstream blockbusters like Furious 7 and Aquaman, Wan still rankles at the classification of the original Saw as “torture porn.” “There was a lot of thought and craft put into the screenplay, and so it felt like a derogatory term to describe it,” he explained to The Hollywood Reporter this June. “It was eventually used to describe the subgenre that it became — and Saw was a big part of that particular movement — but I definitely wasn’t too excited about that term.”

Wan’s co-writer on Saw, Leigh Whannell, has been a bit less vocal in his criticisms of the term, but has admitted to tiring of graphic violence as a crutch in horror. “I think the violence on screen has reached a certain point where that taboo has been broken,” he told JoBlo in press for Saw III. “There’s only a couple more things you could do. What are you going to do, have someone castrating themselves for real on screen? At some point, you’re going to have to put a lid on it and say, ‘We’ve done all this.’”

The franchise pivots hard into graphic gore with Saw II, the sequel rushed into cinemas the next year. Saw II was actually a rewrite of an original screenplay by director Darren Lynn Bousman, The Desperate, retrofitted to the franchise. Originally, none of the three creative forces involved with Saw and Saw II – Wan, Bousman, and Whannell – wanted anything to do with Saw III. “In a lot of [Saw II] interviews I said that there would not be a Saw III,” Bousman confessed in press for Saw III.

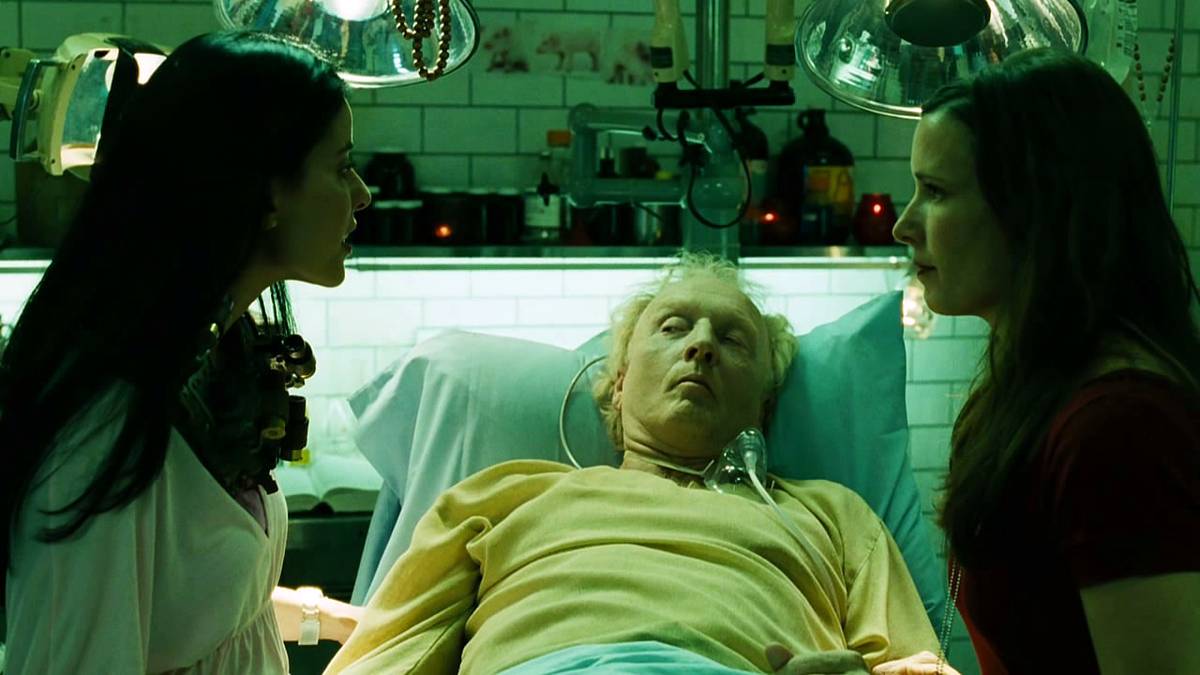

However, when producer Gregg Hoffman passed away prematurely, the three decided to shepherd Saw III into cinemas as a tribute. As Bousman recalls, “We were sitting there and we were like, ‘You know what? They’re going to do Saw III with or without us, so let’s do it for Greg.[sic]’” That sets up the vibe for Saw III, which finds a surgeon named Lynn (Bahar Soomekh), sharing the director’s middle name, desperately fighting to keep the franchise’s flagship cancer-ridden killer John Kramer (Tobin Bell) going for one more Saw film.

There’s an exhaustion to Saw III. The opening moments join Matthews in the aftermath of the climax of Saw II, trapped in the bathroom from Saw. He is chained to the floor. There is a saw nearby. It’s all very familiar. Matter-of-factly, understanding he’s a protagonist in a Saw film, Matthews picks up the saw, rolls up his jeans, and takes his sock off to use as a gag. It’s business as usual. That’s what the audience expects. However, stopping to think about it, he then uses a nearby shattered toilet lid to break his foot instead. Saw III rejects the saw.

Like most major horror franchises, the Saw films go back and forth in their opinion of John Kramer. He is the closest thing that the series has to a main character, and so the franchise’s perspective tends to align with his own. Some of the films seem to enthusiastically embrace his rationalizations for the torture that he inflicts upon others, treating them as some grim millennial self-help. Other films are somewhat more skeptical, suggesting that he is lying to himself as much as others.

From the beginning, Saw III dismisses Kramer’s justifications that these trials serve any purpose beyond torture and sadism. Examining an early trap, Detective Kerry (Dina Meyer) notes that the door to the room was welded shut, meaning the trap was inescapable. When she is trapped herself, she retrieves the key that should unlock her torture mechanism, but discovers that it doesn’t work. The game was rigged. It was unwinnable. It was really just an excuse for some grotesque body horror.

Saw III adopts a different structure than Saw or Saw II. The film’s protagonist is Jeff (Angus Macfadyen). Jeff isn’t a victim in any elaborate trap or a police officer trying to catch Kramer. Jeff’s son was killed in a hit-and-run. He wakes up in an old, abandoned abattoir and effectively wanders through a series of complicated torture mechanisms that inflict pain and suffering on other people. His primary function is to witness this suffering. He can also decide whether to stop it.

Jeff is an audience surrogate wandering through his own Saw film. Saw III is decidedly lurid. The first trap that Jeff encounters finds a naked woman named Danica Scott (Debra Lynne McCabe) chained up and sprayed with ice-cold water. “Why are you doing this to me?” Danica demands. It turns out she was a witness to the death of Jeff’s son, but wouldn’t testify. “I didn’t do anything to you!” she screams. Jeff replies, “That’s exactly it. You didn’t do anything.” The irony seems lost on him as he stands by and watches her suffer.

Soomekh has acknowledged struggling with the graphic violence in Saw III. “I think I asked Darren a couple times,” she confessed to IGN when asked about it. “From what I understand, this is what the fans want.” According to Hoffman, the decision to increase the amount of onscreen gore in Saw II was in response to fan feedback. As such, Jeff’s role in Saw III as a voyeuristic and passive observer of this graphic violence feels like an indictment of the franchise’s audience.

After all, the original Saw feels like a movie heavily indebted to David Fincher’s Se7en, another movie about a self-righteous serial killer with a passion for elaborate torture mechanisms. Se7en remains one of the great depictions of urban anomie in American mainstream cinema; of the disconnect that people feel from one another in these anonymous cities. So much of the Saw franchise unfolds in eerily empty and abandoned communal spaces like classrooms, hospitals, and clinics.

Saw III argues that Kramer’s motivation is a desire to shake his victims out of apathy, to wake Jeff up from the stupor following the death of his son. However, he also seeks to awaken some empathy in Lynn. “Why are you living with the dead when you have such a beautiful family, a husband who is indeed alone, a daughter who needs her mother, patients who need a competent physician who looks them in the eye and treats them like human beings?” he asks her. What if the audience and the filmmakers lack that same empathy?

Of course, the irony is that Kramer’s work has been misunderstood — perhaps in the same way that the original Saw was misunderstood. It turns out that Kramer’s apprentice, Amanda, has been rigging the traps to make them inescapable. She’s also been killing survivors. This is something of a clumsy retcon, in that the original Saw makes it clear that Kramer knew that Amanda hid the key to Adam’s (Leigh Whannell) chain in the water where it would go down the drain, something Saw III omits in its edit of the flashback.

Still, the point stands. Amanda was supposed to be Kramer’s lasting legacy, a lost young woman who survived her trap and was seemingly transformed by it. Instead, she’s a monster. In his final hours, John builds one last trap to test her. She fails spectacularly, and so Kramer has failed spectacularly. There was reportedly an even more explicit scene in which Kramer would acknowledge his regrets over what he has done, although actor Tobin Bell admits to being “glad they cut that scene.”

Still, Kramer’s left dying in an abattoir, confronted with the complete failure of his grand artistic work as his successor runs it into the ground. Given that Saw III marks the last involvement of Wan and Whannell in the franchise, it feels like a none-too-subtle metaphor. Saw III seems to torch the franchise on the way out the door. The film ends with Jeff shooting Amanda and murdering Kramer with an electric saw, which triggers an explosive collar around Lynn’s neck. It’s the franchise equivalent of “rocks fall, everyone dies.”

The decision to kill Kramer three movies into the Saw franchise arguably stunts the series. Somehow, Bell goes on to appear in six of the next seven entries, with Saw X promising more Kramer than any previous entry. The series contorts itself into weird shapes to justify bringing Bell back, creating an increasingly tangled continuity of prequels, interquels, and flashbacks. Bousman argued Saw III was intended as the closing chapter of “a complete story. It is one complete story, basically. It is a tragic epic.” This wasn’t how it turned out, but it was meant to be.

Saw III is a remarkable franchise film, one that seems to hold both itself and its audience in sheer contempt. However, it was also a massive success. Its opening weekend was the biggest launch for the franchise and for Lionsgate to that point, and the biggest opening for the Halloween holiday weekend to that point. There was no way that John Kramer could be allowed to rest in peace. The pieces may have been smashed, but the game was far from over.