Warning: This piece on how Godzilla Minus One is about trauma and hope contains mild spoilers.

I’m not the biggest fan of Godzilla, but Godzilla Minus One, Toho’s 70th anniversary project, made me a believer.

While the American productions under Legendary Pictures have done okay for the most part and are coming out at a frequent enough pace, it’s been a long time since Toho released a new Japanese Godzilla film. That film, Shin Godzilla, was a bleak and almost hopeless examination of the King of the Monsters, ending on a note that Japan and the planet itself are doomed. Godzilla has, when handled properly, been a symbol for whatever the director of the day wishes him to be, and in Shin Godzilla, he’s a symbol of natural disaster, something that cannot be controlled and will almost certainly end us all. Meanwhile, the Legendary films often show him as a big monster that needs to be defeated, focusing more on the spectacle than anything else.

If you wanted just a simple review on whether Godzilla Minus One is good, the answer is an emphatic yes. While at a press screening hosted by the Japan Society, I saw it capture everything that makes the franchise as special as it is and prove that you can make a blockbuster experience even with a small budget of $15 million. But more importantly, Godzilla Minus One is remarkable for what it says about Godzilla itself and the impact that Godzilla has on the people he leaves behind in the wake of his destruction. In Godzilla Minus One, Godzilla isn’t a metaphor for nuclear war or natural disasters, and he’s certainly more than just a big monster to be defeated. Here, Godzilla is a symbol of trauma.

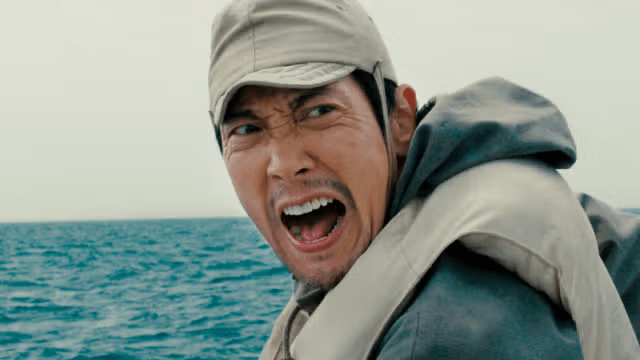

The film follows one Koichi Shikishima in the aftermath of World War II. Shikishima was a kamikaze pilot who abandoned his mission at the last moment and instead encountered Godzilla. After hiding while watching everyone around him die, Shikishima returns to his home, only to find it destroyed in the war, and he’s shamed for not giving his life for the cause. He attempts to rebuild his life by taking care of a baby and living alongside her adoptive mother, Noriko, but he can’t overcome the guilt of what he did or, rather, what he didn’t do. Flash forward a few years when Godzilla reappears, and it’s like he never left that island in that Pacific Theater.

If there’s one phrase that the movie does throw around a lot, it’s that the war never ended. Most of the cast can be divided into two camps: veterans and non-combatants. The veterans are all haunted by World War II, not only by how it changed Japan but also by how it affected them individually. Shikishima has night terrors about what happened in the war and has such extreme imposter syndrome that he believes he’s a walking corpse and actually died a long time ago. Over time, these veterans are able to heal, but that wound is ripped right open when Godzilla attacks.

Godzilla has always been a metaphor for nuclear destruction, but that carnage is taken to the next level thanks to the fears that people had of nuclear armageddon during the Cold War. Characters openly talk about the fear of rising tensions between the US and the Soviet Union and how those tensions are escalating the production of nuclear weaponry. Plus, with the continued development and refinement of the atomic bomb, Godzilla Minus One implies that it’s not a question of if war will return to Japan but when. When it does, it’ll be even worse than before. So, of course, when Godzilla returns to Japan, he’s even larger and more powerful than before. The specter of war has only grown larger, and with more powerful nuclear bombs, the fear that Godzilla represents has grown alongside it.

The Godzilla of Godzilla Minus One is classic in a lot of different ways. It’s not just because of how he walks, which is almost exactly the same as how he did in the original 1954 version, or how he’s the only monster present for the Japanese people to contend with, but because of how much of an inevitability he is. He is destruction. When he comes, it’s not a question of how to destroy him (at least at first), but rather how to survive him. He effortlessly kills people just by walking and can’t be killed by conventional methods. The military may attack him, but it doesn’t weaken him at all, only offering up a new target for him to direct his rage towards. Shoot him with a battleship? He’ll redirect his focus there, then go back to the task at hand.

You still have your standard hallmarks of the King of the Monsters, like his brutal heat ray, as the film calls it, and it fully captures the same impact that the atomic bombs did when they dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Mission accomplished at directly replicating that carnage, Godzilla Minus One. All people can think about after he attacks is the fear of what he’ll do when he returns. Who knows when it will be, but he will come back, and he will kill again. You won’t be able to sleep at night knowing he’s out there somewhere, and if you think about it, you’ll only end up in a spiral of fear and terror that will leave you debilitated.

And yet, Godzilla Minus One is a movie about hope. Despite the overwhelming terror that Godzilla represents, his presence only serves to try and unite people together. If we only just put our differences aside and choose to put all of our efforts into defeating this specter of war, then true peace can be achieved, and Japan can be rebuilt. One of my favorite scenes in the film takes place right in the middle, where a group of veterans are asked to risk their lives to try and stop Godzilla before he destroys Japan. It’s made abundantly clear that they are not being forced to do this. They can leave if they want, and no one would hold it against them. But most of them stay. Why? Because this time, they had a choice.

During World War II, many Japanese soldiers were forced to give their lives for their country, even if it was clear that there was no hope of victory. Shikishima was one of those soldiers who were set to give his life for a cause that was all but dead. The odds were impossible back then, much as they are here when faced with Godzilla. But the fact they had a choice at all is what gives them determination. They know the risks, and they can choose to walk away from it all, but they stay because now they’ve decided to accept the risks. If they die, at least it was their choice. They are choosing to come face to face with the trauma of their past in an effort to protect the future of Japan and the world by stopping Godzilla.

As these veterans are preparing for combat, they’re joking and smiling as they do so. They know what’s in store for them, but they believe that, even if there’s a slim chance that they may live, that’s at least better than the odds they faced in World War II. All of the characters have their choices to make, whether it be the veterans to protect the non-combatants by making sure they never see the horrors of war or the non-combatants trying to help anyway because they care about the future of their country. They all have hope that Godzilla can be stopped and that there is a future for all of them when he’s defeated.

I won’t say how Godzilla Minus One ends or what happens to any of its cast members, but there’s a certain level of optimism that peaks around the corner every so often in the film. Yes, this is still a drama about the effects that war has on a country and people, but it’s kind of perfect that this movie is the 70th-anniversary piece for Godzilla. It’s almost as if Toho is saying, “Look how far we’ve come,” not only from the inception of the franchise but from Japan’s place in the world after World War II to now. That sense of national pride is still very evident in Godzilla Minus One and instills a sense that the darkness can be overcome and there will always be a light on the other side.

Of course, I have no idea if Godzilla Minus One is just repeating themes and ideas that the franchise has already worn into dust. This is the franchise’s 38th film, after all, and I know for certain that I haven’t seen all of them. But there’s a lot of depth to Godzilla Minus One that feels completely different from the ones I have seen. There’s a human core of the film that is very easy to understand and convey and shows how all-consuming trauma and war can be. But it also asserts that trauma can be overcome and a future can be made wherein the next generation is safeguarded by their predecessors. Does it come across as hokey? Maybe at some points, but it all comes from a place of authenticity, making Godzilla Minus One easily one of my cinematic highlights of 2023.