The most striking thing about Chris Chibnall’s Doctor Who is how old-fashioned it feels, as if trying to recreate the show’s earliest seasons as 21st century television.

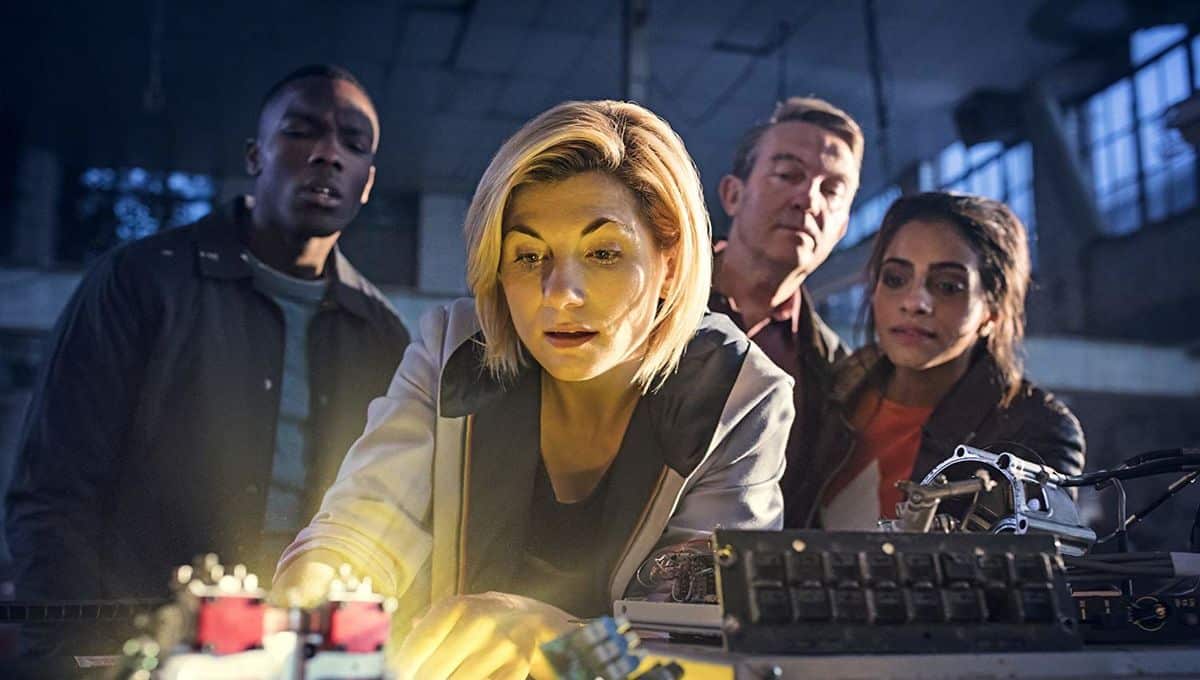

Chibnall took over Doctor Who in 2018 and deserves a lot of credit for updating certain aspects of production. He notably cast Jodie Whittaker in the lead role. Excluding charity sketches and out-of-continuity supplemental material, Whittaker was the first woman to play the part since the show’s launch in 1963. The rest of Chibnall’s casting has given the series its most diverse casting ever.

Under Chibnall, the production invested in anamorphic camera lenses to give the show a crisper and more modern look. New composer Segun Akinola adopted a minimalist approach the soundtrack in contrast to the bombastic scores of his predecessor, Murray Gold. Chibnall’s first season cannily exploited location shooting in South Africa and Spain to give the series a more international feel.

These moves have all garnered a great deal of attention and discussion, creating a sense that Chibnall has radically overhauled a series that has been on the air (relatively) consistently since 2005. However, despite some vocal criticisms of the show’s diversity, the gender switch of the main character, and the overall attempt to modernize production, Chibnall’s Doctor Who has been surprisingly narratively conservative.

Chibnall’s Doctor Who is notably less politically assertive than the work of his direct predecessors, Russell T. Davies and Steven Moffat. At one point, Davies killed off the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and shoved him into a Downing Street cupboard as part of an allegory about the Iraq War. In his final season, Moffat had the Doctor punch racists and topple capitalism.

Chibnall’s Doctor Who has been defined by passivity. The Doctor is often an observer of events rather than an active participant. This is most obvious in the “historical” episodes. Under Chibnall, the Doctor has encountered real-life figures like Rosa Parks (Vinette Robinson), King James I (Alan Cumming), Ada Lovelace (Sylvie Briggs), and Noor Inayat Khan (Aurora Marion). Each of these stories has the Doctor introducing the characters to the audience.

Under Davies, Doctor Who indulged in “celebrity historicals,” throwing the Doctor into contact with iconic figures like Charles Dickens (Simon Callow), Queen Victoria (Pauline Collins), or William Shakespeare (Dean Lennox Kelly). Moffat carried on the tradition with Winston Churchill (Ian McNeice) and Vincent Van Gogh (Tony Curran), before gleefully parodying it by teaming up the Doctor with Richard Nixon (Stuart Milligan), Robin Hood (Tom Riley), and Santa Claus (Nick Frost). The point was always the spectacle.

In contrast, the Chibnall era of Doctor Who is consciously aiming towards educating its younger viewers on figures who might be more marginal and less celebrated. It’s notable that — outside of a brief resurgence with H.G. Wells (David Chandler) and George Stephenson (Gawn Grainger) during the Colin Baker years in the ’80s — this approach to historical figures has not really been a feature of Doctor Who since the mid-1960s.

A surprising amount of Chibnall’s creative choices consciously hark back to the show’s earliest days, an era when the Doctor was only hazily defined and before the show had a central mythology. (Many of those episodes are now lost.) Indeed, even Chibnall’s reinvention of the opening credits with a more psychedelic and abstract sensibility recalls the original opening credits to the series.

However, one of the central tensions of Chibnall’s tenure on Doctor Who has been struggling to update these templates and elements for modern television production. Chibnall’s vision of Doctor Who strongly recalls the show’s roots but often runs aground when translating those old-fashioned aspects into contemporary storytelling.

Chibnall’s primary cast now includes four credited leads, the Doctor and her three companions. Under Davies and Moffat, the primary cast was usually two characters. It occasionally swelled to three during the Moffat era, but one of those three leads was always a secondary lead.

Historically, the show has tended towards a single Doctor and single companion. There are only a handful of exceptions. When Tom Baker passed the role to Peter Davison, Davison was crowded out with three companions to buttress the show during a difficult transition. However, one of those companions was killed off before the end of the season, making the cast more manageable.

The only time Doctor Who consistently featured four leads was during its earliest years. In the first season, the Doctor (William Hartnell) traveled through time and space with his granddaughter Susan (Carole Ann Ford) and two of her teachers, Ian (William Russell) and Barbara (Jacqueline Hill). When Susan left, she was replaced with Vicki (Maureen O’Brien). It is notable that Chibnall’s TARDIS crew, along with Yasmin (Mandip Gill), also includes pensioner Graham (Bradley Walsh) and his grandson Ryan (Tosin Cole).

Unfortunately, Chibnall struggles with the reality that modern television pacing makes it very hard to balance four main characters while building a world and telling a story within 45 minutes. Characters on classic Doctor Who were arguably more archetypal and generic than their modern counterparts and so did not need development. The pacing was slower and the stories were longer.

As originally conceived, Doctor Who existed in the context of the BBC’s mandate as a public service broadcaster. The original intention of Doctor Who was to educate younger viewers. The twin prongs of this educational function were reflected in Susan’s teachers; Barbara was a history teacher and Ian was a science teacher. The show would alternate historicals with science fiction stories.

These early episodes were the only time that Doctor Who engaged in pure historicals — stories set in the past without an outside science-fictional element intruding into the narrative. The historical quickly became outdated. Since the late ’60s, with a single exception, it has been customary for Doctor Who episodes set in the past to feature alien monsters or rival time travelers.

It often seems like the Chibnall era longs to return to that classic and pure historical setting. Episodes like “Rosa” and “Demons of the Punjab” do feature external elements, but often at the fringes of the narrative. These stories are focused on depicting real historical events, on teaching children about the importance of the American Civil Rights Movement or the Partition of India.

Unfortunately, it is now impossible to conceive of Doctor Who without monsters, and not just because of merchandising demands. As a result, Chibnall has to balance historical figures with fanciful fantasy narratives, clumsily and inelegantly. In “Spyfall, Part II,” The Doctor whisks Noor Inayat Khan through time before returning her to 1943, a year from her torture and death at Dachau.

Chibnall also draws from Doctor Who’s earliest science fiction stories, owing a clear debt to writer Terry Nation. Nation was responsible for writing the second, and arguably defining, Doctor Who story. Known as “The Daleks,” the story not only introduced the iconic omnicidal pepper pots, but it also defined the concept of “monsters” that would percolate through the rest of the show’s history.

As a writer, Nation was heavily influenced by pulp serials. His stories often feature alien worlds populated by hostile wildlife, haunted by mutants, and visited by daring astronauts. Nation was very much engaged in world-building, and his style played to the strengths of the original ’60s show. Nation could reliably churn out daring space adventures neatly broken into six half-hour installments.

Chibnall’s science fiction work often feels of a piece with Terry Nation. The hostile alien environment in “The Ghost Monument” recalls the eponymous planet in “The Keys of Marinus.” The structure of “Spyfall, Part II” recalls that of “The Chase,” as the Doctor is hunted through time by a deadly nemesis; Chibnall just replaces the Daleks with the Master and symbolic Nazis with actual Nazis.

The problem is that Terry Nation’s sensibilities were already retro in 1963. More than that, Nation’s storytelling worked in a serialized format, broken out over six weekly half-hour adventures, allowing for cliffhangers and world-building.

Chibnall’s science fiction scripts often try to cram too much into their 40-odd minutes. Episodes like “The Ghost Monument,” “The Tsuranga Conundrum,” and “The Battle of Ranskoor Av Kolos” grind to a halt for exposition, and many of the smarter ideas are often bluntly stated rather than actually shown. Characterization takes a back seat to make room for high concepts.

This is the tension of the Chibnall era, a yearning for an older iteration of the show that fails to account for how television has changed in the intervening years. There is no understanding that modern audiences are more familiar with the show’s structure and no acknowledgement that things that were capable in six half-hour episodes cannot be replicated in a single 40-minute installment.

In production terms, Chris Chibnall has helped to push Doctor Who boldly into the future. Unfortunately, the show’s storytelling is trapped in a time warp of its own.