Back in 2013, in the lead-up to inFamous: Second Son’s launch, creative director Nate Fox praised the value of the DualShock 4’s touchpad, saying it provided more opportunities for interactivity, more “verbs.” The haptic inputs involved in that project were designed to simulate the actions occurring on screen to better embody the player as Delsin. As exciting as the idea was, that execution ultimately amounted to more active participation in the killing of NPCs or a more novel version of “press X to open door.” Those added interactive elements existed within the established framework of the action adventure, meaning that the narrative possibilities of rethinking the deployment of verbs in gaming went unfulfilled.

However, developers in the years since have made great strides in expanding what games can say by reimagining what players can do. In video games, meaning is only meaningful if the gameplay coheres with the narrative. Stories are constrained by their frames of reference, so the number of themes that first-person shooters or animal mascot platformers can effectively canvas is limited. A person with a gun can only solve so many problems. Generations-old mechanics continue to dominate the mainstream, but developers are seeking ways to gamify more verbs to extend the conversations of gaming beyond conflict.

Death Stranding is a recent example of trying to incorporate more verbs. Kojima Productions turned its ambitions away from combat and stealth to focus instead on traversal and the building of paths. The archetypal adventure game structure was overlaid with the challenge of how best to deliver packages from one NPC to another and how to allow other, asynchronously connected players to benefit from your trails. Finding ways to connect settlements in a fragmented world was both a gameplay goal and mechanic, and that allowed for a sense of thematic unity with the story’s goal of reconnecting a divided society. That story could not have worked as a Metal Gear Solid or a Killzone.

Characterization is another story element that has the potential to benefit from mechanical innovation. In most games, the protagonist is slave to a predetermined character arc delivered primarily through cutscenes or a cipher with no real agency. Morality mechanics provide a layer of player-sourced nuance, as in Mass Effect’s Paragon/Renegade duality, but even then the character is merely the agent of the player’s will. Personality is determined by more than just what a person says — tone of voice and non-verbal cues are equally important. The conveyance of these factors through interactive elements remains woefully under-considered, but a benchmark is to be found in Life Is Strange: Before the Storm.

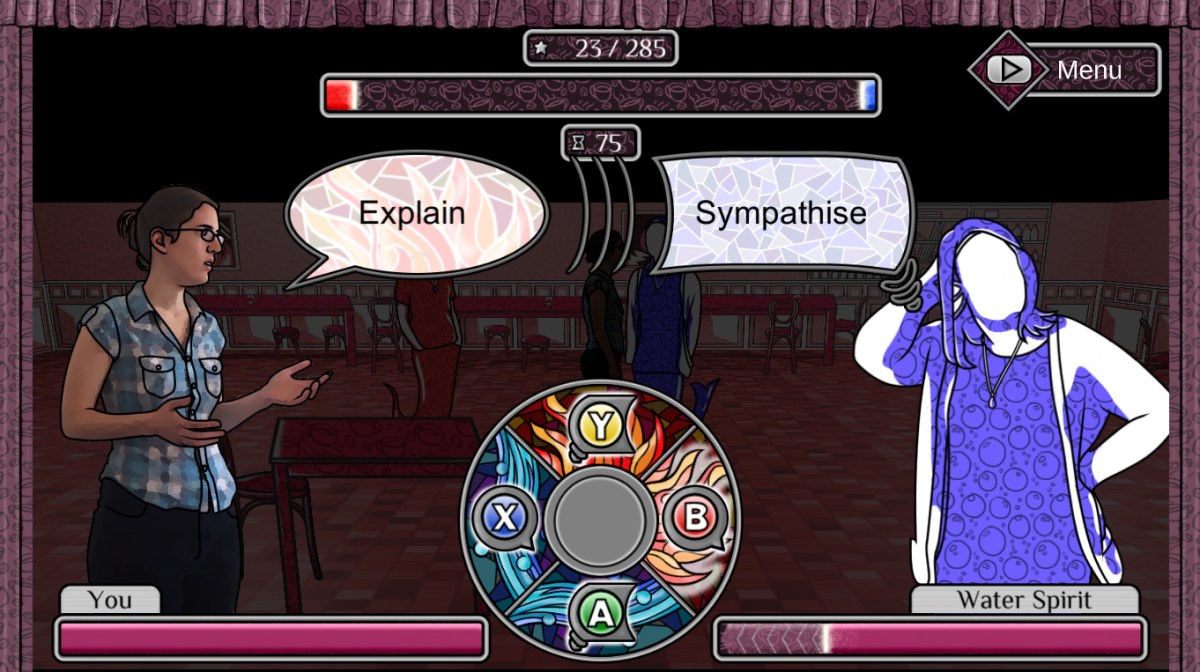

In switching lead characters from Max Caulfield to Chloe Price, Deck Nine sought a replacement for the time-bending functionality, settling on the Backtalk mechanic. Backtalk puts Chloe’s antagonistic, sarcastic personality front and center in a series of conversation challenges. Elemental Flow and Chorus are two games that will expand on that idea by gamifying dialogue choices, making conversations into battles that will be determined by the combatants’ predilections, personalities, and emotional states.

One might argue that these designs strip dialogue of its meaning and reduce it to just another battlefield, but the literary and critical heritage shows any such assertion to be false. Since ancient times, debate has been a method of reaching conclusions across competing viewpoints. From Socratic dialogues to Hegelian dialectics, contests of wills enacted through the deployment of facts and the use of logical reasoning have enabled the development of morality, philosophies, and even societal structures. A battleground of ideas is far different to a Helghan or a Reach because words carry meaning where bullets do not. An example of that in action is last year’s acclaimed Disco Elysium, which is recognized as much for its ideas as its ludicrousness.

Another storytelling element that can be better engaged by changing verbs is emotion. Many games focus on adrenaline-pumping spectacle interspersed with cutscenes intended to pull on the heartstrings to the detriment of tonal consistency. The emotions such games strive to engage never materialize. In contrast to this tendency is Eastshade, an RPG about painting that makes players consider composition and framing.

The pace slows to a crawl, and the result is what may well be the most relaxing game of 2019. Similarly, Crytek’s 2016 VR adventure The Climb reimagines traversal mechanics to make climbing its virtual cliffs a genuinely arduous task. That game features no real story to speak of, but its mechanics could readily be co-opted into an adventure modeled after the 2018 documentary film Free Solo for a harrowing tale of human struggle against nature. Watch Dogs showed how hacking (though simplistically portrayed) can allow for rumination on the technologization of society.

Every interaction with a video game is a verb. The player pushes a button and action occurs on screen. This simple truth is generally accepted as a matter of course, with the result being that playable characters run, jump, shoot, stab, and generally perform physical actions. Verbs are so much more than that, though. Look, think, create, care, convince, listen, suffer, empathize. All of these mundane actions have appeared in games such as Perception, Gone Home, Papers, Please, Dreams, and That Dragon, Cancer, and the wealth of experiences and emotions available in just that short list shows just how much potential lies in thinking about ways to create gameplay for new verbs and to create new gameplay for old verbs.