Clint Eastwood turned 90 years old yesterday and has a career that spans eight decades. He is one of the enduring embodiments of American masculinity and instantly recognizable across the world.

However, Eastwood is a figure of surprising complexity and nuance. As familiar as his screen persona might be to audiences, Eastwood has spent a lot of his career shading the edges of the rugged archetype that he helped to codify. If Eastwood embodies a certain brand of American masculinity, he has also thoroughly explored it.

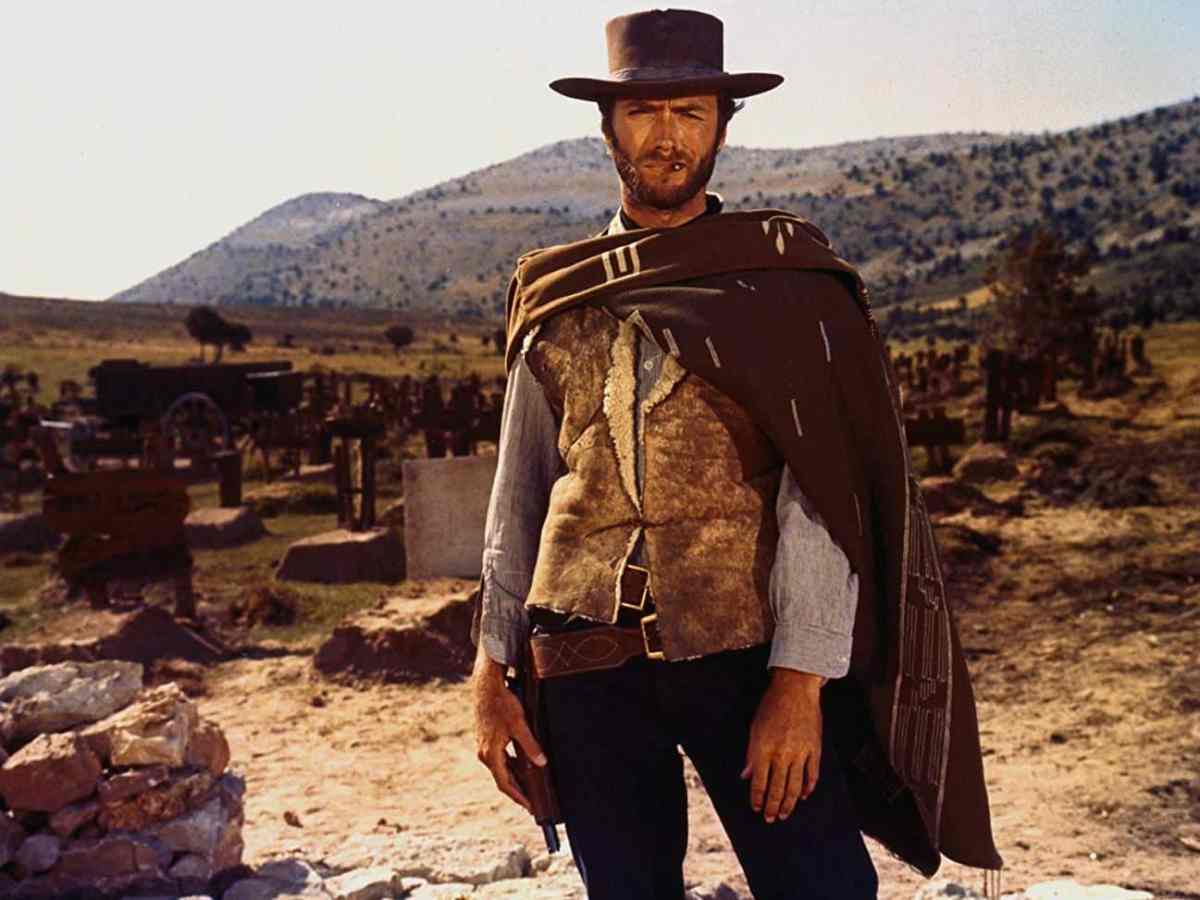

Some of his earliest roles were also his most iconic and influential. The complexity was there from the beginnings of his big-screen career. Having established himself as a regular on the television western Rawhide, he transitioned into cinema by taking the central role in Italian director Sergio Leone’s loose “Dollars” trilogy.

The Dollars trilogy offered a more ambiguous version of the cowboy archetype than American audiences were used to seeing. Eastwood’s anonymous drifter was far removed from the traditional leads in Ford westerns starring John Wayne. He was skinnier, frailer, and more vulnerable. He was prone to being tortured or captured but was always quick-witted enough to escape.

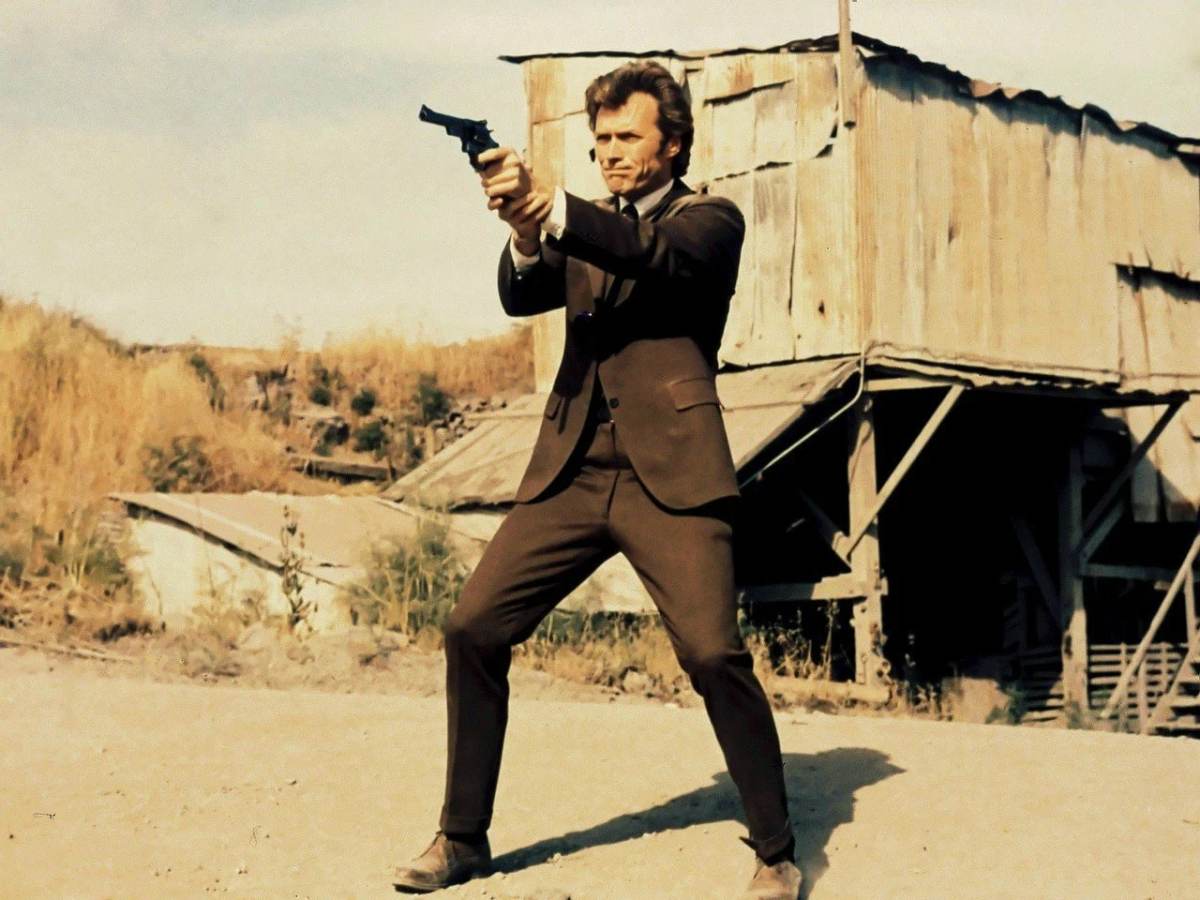

However, by the early 1970s, Eastwood was offering audiences a reassuring depiction of American masculinity. In a time of national unrest, Eastwood offered cinemagoers an ideal of American manhood in contrast to many of his contemporaries. “Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino play losers very well,” he explained at the time. “But my audience likes to be in there vicariously with a winner.”

In 1970, as America came to terms with the horrors of Vietnam, Eastwood took his audience back to the moral clarity of the Second World War in Kelly’s Heroes. In 1971, with anxieties about feminism unsettling male viewers, Eastwood gave those fears form in Play Misty for Me. As Watergate rocked the nation in 1973, Eastwood played an almost supernatural frontier avenger in High Plains Drifter.

Eastwood was an anchor in a turbulent decade. Harry Callahan — Dirty Harry — remains one of Eastwood’s most iconic roles. The San Francisco cop’s clear-cut black-and-white morality offered a response to the hedonism associated with the city in the late 1960s. Dirty Harry even pits Harry Callahan against the Scorpio killer (Andrew Robinson), an obvious stand-in for the Zodiac. Harry could stop the madness.

At the same time, Eastwood was already playing against that archetype. The Beguiled featured Eastwood as a vulnerable and wounded Yankee soldier who becomes the object of obsession for an isolated girls’ school in the South. Director Don Siegel described it as a “woman’s picture,” and it plays off Eastwood’s macho persona — his character is constantly outwitted and emasculated by the women around him, rendered increasingly pathetic. The Beguiled did not play well in the United States, but it established Eastwood as an actor with arthouse credentials and complexity.

To pick one small example: As much as he is an American icon, Eastwood is very highly regarded by the cinematic establishment in France. He headed the Cannes jury in 1994. During the height of tensions between France and the United States during the War on Terror, Eastwood won Best Foreign Film at the César Awards three times in seven years for Mystic River, Million Dollar Baby, and Gran Torino.

Eastwood’s later filmography became a lot more varied. When he stepped in front of the camera in the late 1980s and into the 1990s, it was often to showcase a more emotive side of himself. He played a thinly veiled version of John Huston in White Hunter Black Heart and cast himself as a romantic lead in The Bridges of Madison County.

These films pushed Eastwood outside his comfort zone, but even those later films overtly engaging with his established persona felt more reflective. Unforgiven offered an elegiac take on the western genre that established Eastwood as a screen icon. The late Dirty Harry sequel Sudden Impact played Harry Callahan off a female avenger (Sondra Locke) trying to impose her own justice on the world.

Heartbreak Ridge was a war film about training for the low-stakes (and slightly surreal) invasion of Grenada. The duology of Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima looked at the familiar narrative of the Second World War from two unusual perspectives: the propaganda battle at home and the Japanese experience. These are thoughtful and mature films.

This reflectiveness runs through Eastwood’s later films. Many of Eastwood’s later characters are shaped by regret and loss, often defined by strained relations with their children. Even a potboiler like Absolute Power featured a subplot dedicated to the strained relationship between Eastwood’s character and his adult daughter (Laura Linney).

In many cases, this split results from the Eastwood character’s devotion to his work. In In the Line of Fire, Secret Service Agent Frank Horrigan drives his family away as he obsesses over his failure to save John F. Kennedy. In Million Dollar Baby, gruffy gym operator Frankie Dunn treats young boxing prodigy Maggie Fitzgerald (Hilary Swank) as a surrogate for his own estranged daughter.

Eastwood’s skepticism of this absent father figure becomes increasingly obvious in his later films. The Mule stars Eastwood as Earl Stone, a dapper bow-tie-wearing Korean War veteran who seems like he could just as easily have been played by Jimmy Stewart. Stone is affable and charming, incredibly likable, but he is introduced missing his daughter’s birthday to attend some horticultural awards.

The Mule plays almost as a parody of this familiar narrative. Stone frequently misses family occasions for what are seemingly trivial professional reasons. Desperate to reconnect with his family, Stone becomes a drug runner to earn money. However, he quickly discovers this is not the solution. All his family ever wanted was for him to be present and to stop running away.

This ambivalence towards these familiar masculine archetypes carries over into his other late-period films. Gran Torino focuses on another Korean War veteran, this one decidedly more abrasive and confrontational. Walt Kowalski befriends a young Hmong boy named Thao (Bee Vang) and finds himself drawn into conflict with a local street gang.

So much of the tension within Gran Torino hinges on what exactly Walt is going to do. He is a trained military veteran who is capable of defending himself through the use of force. Gran Torino plays on the expectation that Walt will inflict violence on the criminals in order to protect Thao and his family. It is a classic western setup. However, Gran Torino rejects the idea of violent retribution.

“You want to know what it’s like to kill a man?” he asks Thao, as the young man contemplates revenge. “Well, it’s goddamn awful, that’s what it is. The only thing worse is getting a Medal of Valor for killing some poor kid that wanted to just give up, that’s all.” Instead, Walt offers his own life as a sacrifice, tricking the gang into murdering him and thereby forcing the police to arrest them.

This shading of classic macho screen personas carries over into his other recent work. Eastwood has attracted some attention for his politics in recent years, from his weird performance at the Republican National Convention in 2012 to his comments about the “pussy generation” in 2017. It’s hard not to let this color his later work, especially given the mean-spiritedness of Richard Jewell.

Still, Eastwood’s films remain complex. American Sniper is controversial and divisive, with Seth Rogen likening it to the Nazi propaganda film in Inglourious Basterds. However, it firmly rejects the clichés of American masculinity suggested by Chris Kyle’s autobiography. Eastwood dismisses the superhuman killing machine from the book to focus on the character’s PTSD and vulnerability.

This is also true of The 15:17 to Paris, which starts from a similarly propagandist premise. (The title even evokes the classic western 3:10 to Yuma.) It features four real-life heroes who stopped a terrorist attack on a train traveling from Amsterdam to Paris, recreating that feat on screen. The resulting film is as strange as anything Eastwood has ever made. It feels as much like a bizarro version of Before Sunrise as a celebration of rugged American heroism.

The 15:17 to Paris features four lead performers who cannot act, surrounded by a supporting cast best known for their work in comedy: Judy Greer, Jenna Fischer, P.J. Byrne, Tony Hale, and Thomas Lennon. The film is focused on capturing and celebrating its leads’ mundanity as much as their machismo. It’s as invested in how they order gelato as in how they measure up in a crisis.

There’s no denying the extent to which Clint Eastwood embodies an ideal of American masculinity. However, it’s easy to overlook the extent to which he has spent his career interrogating and examining that ideal. Eastwood understands both his screen persona and the audience’s relationship to that. It is a consistent through line that connects a wide and varied career.