Like a lot of genre film directors, John Carpenter has had a long road towards respectability.

John Carpenter is one of the most quietly influential American filmmakers of the second half of the 20th century. He made his feature film debut directing Dark Star, which he co-wrote with Dan O’Bannon. O’Bannon would take inspiration from that collaboration and write Alien five years later. The year before Alien came out, Carpenter would be inspired by Bob Clark’s cult curiosity Black Christmas to co-write and direct Halloween, the movie that codified the modern slasher movie.

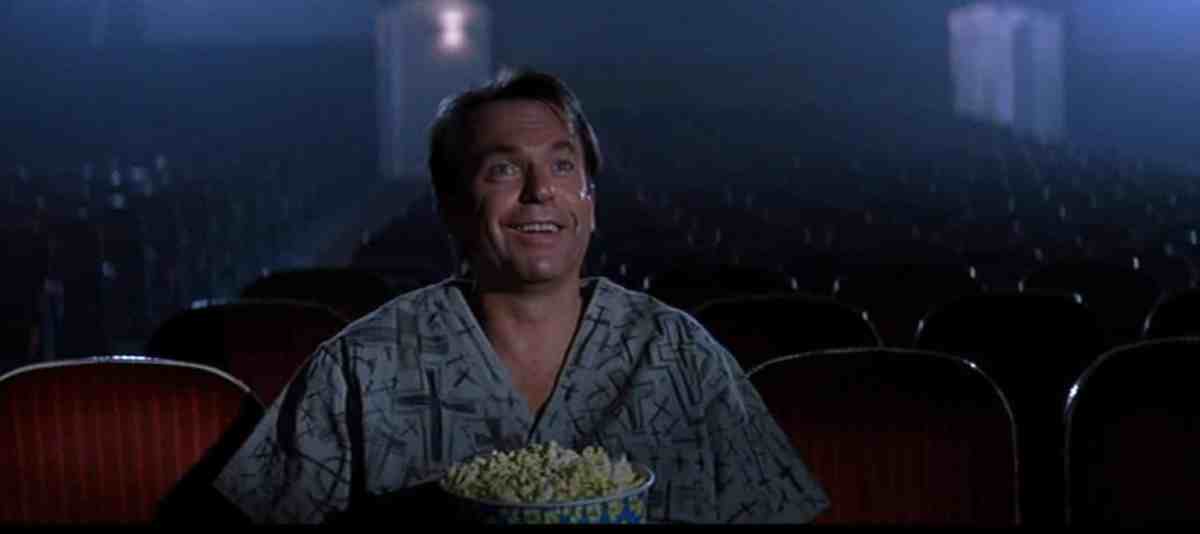

Carpenter has worked in a wide variety of genres over the decades. He has made earnest dramas like Elvis, science fiction action movies like Escape from New York, social satires like They Live, heartwarming romances like Starman, and even the occasional Chevy Chase vanity project like Memoirs of an Invisible Man. As with any filmmaker working that prolifically over a long stretch of time, the quality of the output varies wildly, even if there are a lot of genuine classics in there.

It helps that Carpenter is legitimately a great filmmaker, even if he only tends to be recognized as such in hindsight. In 2019, the Cannes Film Festival recognized Carpenter with the Golden Coach Award at the Directors’ Fortnight, an award that had been given to Martin Scorsese the previous year. Previous recipients include indie darlings Werner Herzog, Agnès Varda, and Jim Jarmusch, along with more recently awards-friendly directors like Clint Eastwood and David Cronenberg.

As director, Carpenter has a unique ability to stretch his budget, to make cheap films look expensive and lavish. Halloween cost just $300,000 to make but earned $70M in initial release. In 1981, Escape from New York built an apocalyptic New York City for $6M. To put that in comparison, the previous year’s Best Picture winner Ordinary People spent more than that to create a sense of middle-class existential ennui.

Carpenter makes B-movies to a AAA standard. A lot of this is down to simple craft. Carpenter shot every one of his features — with the notable exceptions of his first (Dark Star) and his last to date (The Ward) — in anamorphic widescreen. Like many genre directors who emerged in the 1970s — such as George Lucas or Steven Spielberg — Carpenter is a major proponent of the format. He described his second film, Assault on Precinct 13, as “my first in 35mm, Panavision — my first real feature.”

Carpenter believes that 35mm Panavision is “the best movie system there is.” While some directors dislike the format because it makes it harder to frame close-ups, Carpenter’s horror films are built around his use of widescreen. Carpenter’s protagonists are rarely the only object of interest in the frame and often appear like they are about to be swallowed by their environment. The early scenes of Halloween are a great example of this, as the Shape (Nick Castle) stalks Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis).

“Even when we weren’t using the frame to imply that something might be about to happen, as you say, we were using it to create a whole world,” explains cinematographer Dean Cundey, who worked with Carpenter on The Thing. “There are these big wide vistas at the beginning, but with the snow and the mountains and things in the foreground, we still made the frame claustrophobic and used it to confine the characters.” People are small. The world around them is vast and uncaring.

This gets at one reason why Carpenter’s horrors have aged so well in the years since their release. Carpenter is a big fan of the work of H.P. Lovecraft, whose influence on Carpenter’s work is most keenly felt in The Fog, The Thing, and In the Mouth of Madness. Carpenter sheds a lot of the more directly uncomfortable subtext of Lovecraft’s writing, boiling his fears down to their essence: the idea that the world is arbitrary and chaotic, and any attempt to make sense of it is to invite madness.

This is obvious even in Halloween, the template for the modern slasher film. While later films in the franchise (and even Rob Zombie’s reboot) would add layers of backstory and justification to Myers’ killing spree, Halloween presents him as inscrutable. The script credits him as “the Shape,” and he wears a blank (William Shatner!) mask to obscure his face — a mockery of human features, rendered unreadable. The prologue puts the audience in Michael’s head but refuses to explain his pathology.

However, many of Carpenter’s horrors extrapolate outwards from that fear. Assault on Precinct 13 is a film about the unexplained breakdown of moral order, as a decommissioned police station in Los Angeles comes under siege from a local gang in a film best described as Rio Bravo by way of Night of the Living Dead. They Live is built around the idea that the reality that ordinary people experience is simply layered atop a much more monstrous world order. The world is a brutal and violent place.

This is perhaps most obvious in Carpenter’s “Apocalypse Trilogy,” comprising The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness. These three horrors effectively offer three different visions of social collapse. In The Thing, an alien creature arrives from space and begins infecting the crew of an Antarctic base. In Prince of Darkness, a crypt containing the anti-God is found beneath an old Los Angeles church. In In the Mouth of Madness, insanity spirals outwards from a bestseller.

In each of the three films, the potential end of the world is framed as the breakdown of order. They exist at a point where reality itself breaks down. In The Thing, the creature infects its hosts and warps their bodies, destroying any sense of self. In doing so, it also breaks down any sense of trust within the base. The crew turn on one another, unable to tell friend from enemy. The film’s closing shot finds the two survivors of the base unsure — of each other and possibly of themselves.

In Prince of Darkness, biblical prophecy is framed in secular terms as an anonymous priest (Donald Pleasence) and Professor Howard Birack (Victor Wong) investigate a relic beneath a church. God is presented as the force that fills the space between what is known, the unaccounted variables that hold reality together. As such, the Anti-God represents something close to entropy, the nightmarish realization that “common sense breaks down at a subatomic level.” It is disorder and collapse.

In the Mouth of Madness takes the idea to its extreme, implying that reality is a consensus construct, held together by little more than the shared belief in it. “A reality is just what we tell each other it is,” explains Linda Styles (Julie Carmen). “Sane and insane could easily switch places, if the insane were to become the majority.” As in The Thing and Prince of Darkness, there is a sense that concepts like society, the universe, or even reality are only as strong as the bonds that hold them together.

Every generation gets an apocalyptic horror that it deserves, reflecting the fears bubbling away in its subconscious. In the 1950s and the 1960s, horror was dominated by the fear of nuclear apocalypse in films like Them!, Godzilla, The Day the World Ended, and Planet of the Apes. More recent films have tended to lean towards environmental catastrophe, from The Day After Tomorrow to Interstellar to The Happening to Geostorm.

Carpenter’s Apocalypse Trilogy has aged well because it suggests a vision of the end of the world that is not as literal or explosive as those that tend to dominate pulp fiction. Instead, it offers a glimpse of the erosion and decay of a shared reality. These nightmares resonate in a world where it can seem like reality itself is breaking down, where it often feels like people can no longer even agree on a shared reality, and where trust in civic institutions (and other people) is very low.

It is a distinct and unique approach to the apocalypse, one that forgoes a lot of the trappings of the genre. It’s certainly more cost-effective. It also taps into a palpable fear that likely made sense to a post-Watergate and post-Vietnam America, and which has only grown more resonant in the years since: What if the end of the world does not arrive with a bang, but with the slow erosion of whatever has been holding it all together?