“Absolutely terrifying” is how creative director Imre Jele described the responsibility of adapting George Orwell’s Animal Farm into a video game.

The book is an undisputed literary classic. It is “a fairy story,” retelling the Bolshevik Revolution and the rise of Stalin through an inoffensive animal fable, while at the same time exploring Orwell’s recurring themes of doublethink, disinformation, and propaganda.

Not everyone likes it or respects it, but everyone knows Animal Farm, a staple of school curricula even today. “It’s a 75-year-old, historically important book and you mess that up… Like, come on,” said Jele. “So, it’s a hugely scary thing. It’s absolutely terrifying. I feel like that was motivating the team in a good way.”

The nature of adaptation – particularly from a fixed story to an interactive medium – meant that some changes were unavoidable. For example, you can kill off the Stalin-esque Napoleon and have Snowball, the Trotsky figure, run the farm. However, that fundamental concern about the importance of Animal Farm guided the process.

“We also realized this is not a time to add our personal politics,” explained Jele. “Animal Farm stood the test of time for 75 years. What it doesn’t need is Imre innovating some crazy shit which I believe in – because I’m not Orwell.”

Therefore, the cardinal rule was, “What Would Orwell Do?”

With that in mind, assembling the right team was important. Jele said that he was lucky to have the best people available and willing to work with him. Among them were acclaimed performance director Kate Saxon (Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order, The Witcher 3), Assassin’s Creed: Origins’ Abubakar Salim as the narrator, and composer Murugan Thiruchelvam (Surgeon Simulator and trailers for the likes of Game of Thrones, The Handmaid’s Tale, and Birdbox).

Just as important as raw talent, though, was an awareness of the importance and relevance of Animal Farm.

“The people who came on board ultimately were talking about two things,” explained Jele. “They were talking about their personal relationship with the book, how it made them feel when they were a child or they read it as an adult, what it did to them. And the other one is them recognizing that this is more relevant than it’s ever been, unfortunately – or definitely than it’s been in the last 30 or 40 years.”

One of those team members was Tamara Alliot, CEO of Nerial, which was responsible for design and programming on the game. Nerial is best known for the Tinder-infused strategy series Reigns and had released Reigns: Game of Thrones mere days before Jele reached out to them. Nonetheless, Alliot said Nerial was immediately attracted to the idea.

Reigns uses simple game mechanics to challenge players to consider the underlying complexity and unexpected consequences of political choices. The Nerial team has approached the mechanization of Animal Farm with the same sense of opaqueness as Reigns; managing the farm is less about guaranteeing resources and more about determining the level and type of authoritarian oppression perpetrated by the pigs.

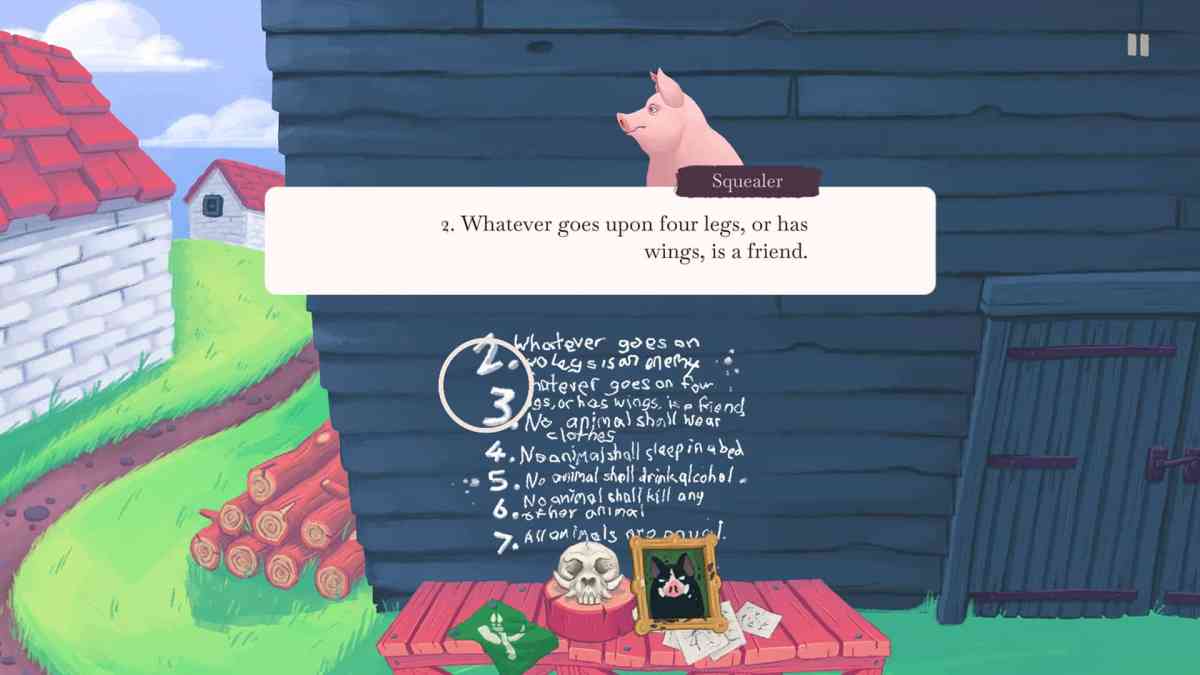

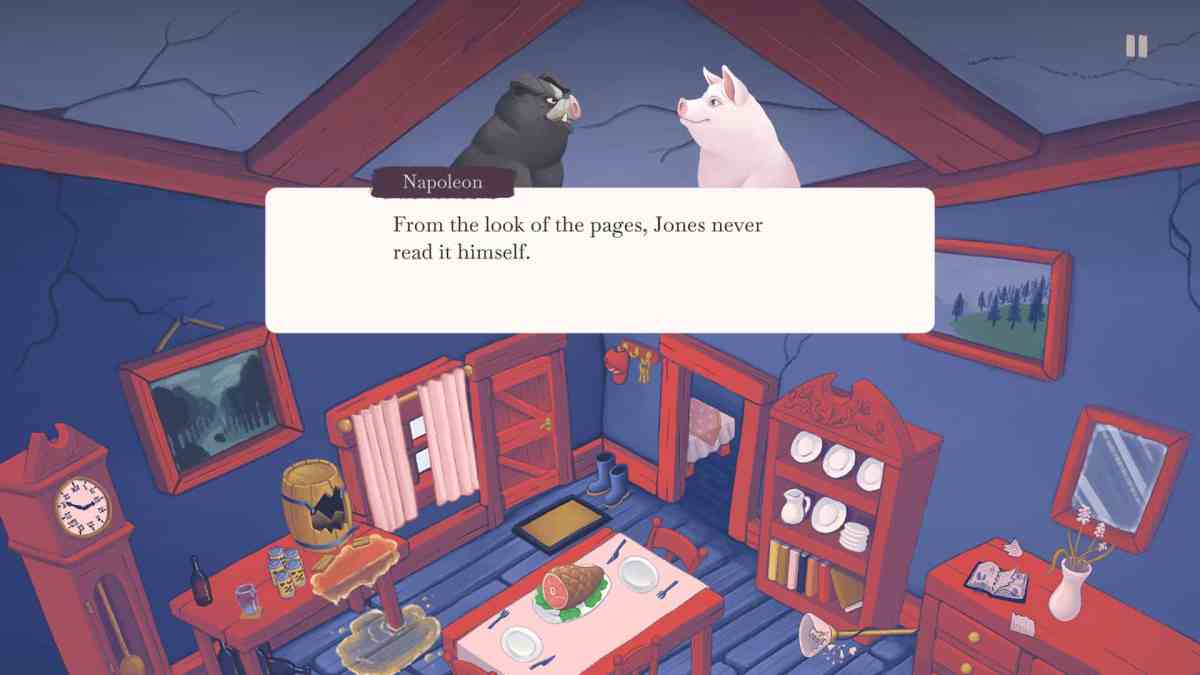

It’s grim, then, but much less so than that brief synopsis might suggest. Orwell’s subtitle for the novella was A Fairy Story, and that manifests through the animal fable narrative and a very approachable writing style. The team on the game has tapped into that spirit. Writer Emily Short’s script is as unadorned as Orwell’s original prose – when she has adapted or added to it, rather than simply imported it – and the visuals also carry the load.

The game plays a bit like a visual novel, as players make choices against mostly static 2D backgrounds. Most scenes are bright and bucolic, with a simplicity and clarity that calls back to retro cartoons and advertising. Alliot called that a conscious decision.

They wanted the aesthetic to hearken back to the 1940s when the book was written. “We didn’t want to put people off who maybe don’t play games a lot, who might be attracted towards playing Animal Farm in its game form but were maybe not super gamers,” said Alliot. “To hopefully attract that sort of audience, the aesthetic needs to be something that they really felt comfortable and familiar with, that looks appealing and in keeping with the period in which the book was written.”

According to Short, who helped to set the direction of the narrative design, the presentation also helps to capture the sense of unexpected depth from the novel: “Because it presents itself in this sort of pseudo-naive way, it kind of encourages you to not immediately have some of the interpretive barriers up that you might otherwise.”

Yes, the first chapter of the book starts with the vice of Mr. Jones and Old Major’s polemic against the status quo of Manor Farm, but it also includes the dream of revolution and the rousing chorus of Beasts of England. Short appreciated the novella’s juxtaposition of politics and narrative techniques, of humor etched into the politics and gloom.

Equally compelling though is how Animal Farm tells a “systemic” story. The fortunes of the farm and individual animals map to actions that can be readily mechanized. For example, characters can direct their efforts towards building or collecting resources for the good of the farm or work themselves to death or be exiled. All those options have precedent in the book and have been gamified to let the player determine what happens.

However, that agency also means that Short had to create alternative branches for Orwell’s story. That expansion could have gone several ways, and Short said she considered extending the timeline further into the Cold War but ultimately chose not to: “I wound up doing a certain amount of research that I then just decided doesn’t fit in the story. It’s interesting. We could add bits about proxy wars involving neighboring farms and stuff, but actually that doesn’t belong here. It starts to become our story, not Orwell’s story.”

However, the game does not practice slavish adherence to Animal Farm. Short also reread 1984 and a number of Orwell’s essays to inform the portrayal of state surveillance and repression of subversive elements within society, among other expanded ideas. While that may be of concern to literary tragics, the Orwell Estate sanctioned the team’s changes without needing to see them; Short and the team proved they could be trusted by explaining their process and intentions.

At the very least, Short and Alliot categorically reject that the game is meant as propaganda in the same way as the 1954 animated film version. Nevertheless, Short also does not shy away from admitting a distinct political bent:

“One of the things that I found really interesting as I was reading some of the contextual material was Orwell writing about how he himself felt compelled to write politically because of the situation that he was seeing around him in the world. That was kind of a moral imperative for him. And while I wouldn’t put myself in the same category as Orwell, I definitely have had this growing sense of this is just where the world is right now; it’s not a place where I feel like it’s even possible to be politically disengaged.”

That was also one of the driving forces behind Jele’s desire to make this game. He has spoken previously of an abiding affection for Animal Farm, born partly from his youth in Hungary during its years as a socialist dictatorship.

In addition to that and the systemic nature of the story that made it seem suitable for a game, Jele said, “There was also a feeling of responsibility. It felt like this is the time this story needs to be brought to people. The way politics works today, I think it’s very important that people look at this, especially seeing if you search on social media for ‘Orwellian’ and then you read how people use that, you can see that they clearly have not read anything from Orwell in a long time, if ever. They have no clue what ‘Orwellian’ means.”

He elaborated that the language of the political class today seems to mirror that of his youth. It utilizes an image of the enemy. For him, growing up, it was about creating a fear of “capitalist spies and saboteurs.” Now, enemies are made of immigrants and terrorists – to say nothing of the vilification of media, the “deep state,” or the “radical left”: “In America in particular you see this pattern of the left telling us about the right, and the right saying things about the left, the same language. You’re the enemy. There is no conversation because you are the enemy.”

Jele despairs of that especially.

“I find that when we talk about political systems, let it be late-stage capitalism or communism, what we see there is these beautiful ideals taken to the extreme and broken,” he said. “The ideals are broken in the process. I think my biggest worry, and I feel the reason almost none of these systems — let it be again capitalism, communism, whatever, all of these systems — the reason they struggle to work is because there isn’t a real discussion about that. Everyone is always strawman fallacies. It’s taken out to extremes and it’s just tribal, single-issue clash. That makes discourse impossible, and that makes political evolution impossible.”

Jele attributed this entire situation of toxic discourse to what he called “weaponized individualism.” Short spoke similarly, referring to a sense of “individualism and individualist rhetoric.” Both talked about the difficulty of communal action against universal problems amid such conflict.

Jele also said that it means people try to hold others to account for old beliefs even though “people should be allowed to change their minds. The world changes around us. It’s okay for me to think differently today than I did a year before because, fuck me, how different is this year going to be than last year at the same time? … If someone changes their mind, they’re called weak-minded, and I’m like — no, that’s growth.”

Providing the opportunity for that kind of growth is ultimately one of the core goals of the team behind Orwell’s Animal Farm. None of them are trying to change your mind, but they are hoping that players walk away with open eyes and approach the world through a lens of critical thinking.

For Alliot, it’s about trying to get people to think more deeply about the subjects that Animal Farm focuses on: “I’m hoping that the game will allow people to get a little bit more in-depth. … An aim for this whole project is just to bring important ideas to new people and to have people revisit it who did not enjoy reading it at school.”

Jele takes that a little bit further, hoping that Orwell’s Animal Farm could be the high point of his extensive career in video games:

“I’m so excited to take this amazing piece of literary fiction and put it in front of people and hopefully engage them in the same way that book engaged me when I read it when I was a young child. To make questions about the world around you and say, ‘That’s unfair. Why did that happen to the animal? That’s unfair.’ And then go out into the world and look around and see unfairness around you and say I’m going to question that. I’m going to act against that. If anyone would leave that game like that, that would honestly be a career top for me. I don’t know how to … go beyond that. I don’t know what other work I can do. It’s an extremely noble and high goal. And, you know, we just hope that we did a good enough job to engage people enough so they can start asking those questions.”

Orwell’s Animal Farm is available now for PC and mobile platforms.