Orwell’s Animal Farm is one of the most affecting games I’ve ever played. As I think back over my time with it, I’m reminded inexorably of Stephen King’s assertion that there are three levels of terror: gross-out, horror, and terror. It’s that last one — that King described as “when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute” — that the game taps into.

In general, most horror games don’t frighten me. Oh look, it’s a horde of zombies that I have to shoot; it’s a wannabe creepy thing that I have to hide from in a rusty cupboard; oh no, if Jason catches me, escaping this gloomy campground will be harder for my teammates. The gameplay usually goes one of two ways: Either it’s derivative of power fantasies, or you spend so much time hiding that it just becomes frustrating and boring rather than tense.

This year, I’ve played Alien: Isolation, Arkane’s Prey, some of the Resident Evil and Amnesia games, and probably a few others that have slipped my mind. They all fell flat for different reasons.

And then Orwell’s Animal Farm came along. It’s not scary in the way those other games try to be. It’s more cerebral, more terrifying.

It joins a tiny list of games that have made me feel anything like the shock and deep unease of my most terrifying real-life experiences: getting swept off a flooded rail bridge, or one time having a snake appear over my left shoulder when I was on the toilet as a kid. (I really wish I were hamming up the “dangers of Australia” with that second one.)

The first of those games was Heavy Rain — particularly The Lizard chapter, where Ethan has to cut off part of his finger. Not only was the scene itself tense, but the consequences were unclear. What would happen if I used the wrong tool? Or if I didn’t take proper care of the wound? Could Ethan succumb to sepsis? Up to that point, I was just playing another more-or-less on-rails game where the consequences were clear. Suddenly, though, I was inside Ethan’s mind and couldn’t tell what might come next.

The other game was Gone Home. I’d never played a walking simulator before, but other media had conditioned me to think that gloomy old mansions and raging thunderstorms presaged horror. And Katie Greenbriar is no Claire Redfield — all she can do is wander around the house and look at stuff. Between the emptiness and the environment, something seemed wrong, but there was no way of knowing until the game divulged its secrets.

What those games have in common, where they gain their spooky power, was in challenging my perception of the rules of video games. That sense of being on uncertain ground is scarier than any Tyrant or xenomorph, and it’s something that Orwell’s Animal Farm has too.

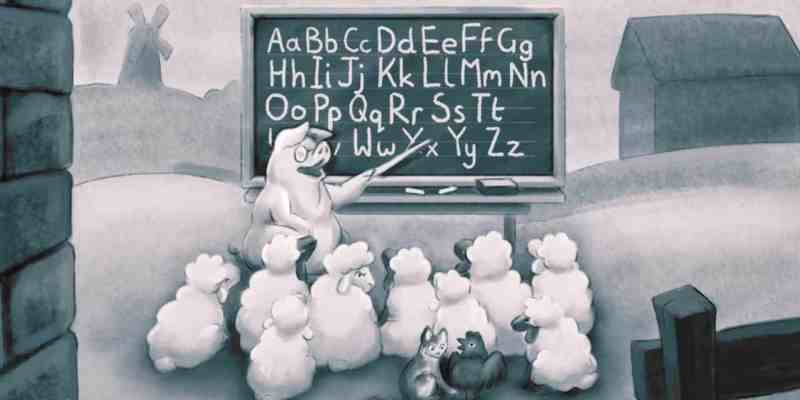

George Orwell’s original Animal Farm allegorical novel is unsettling. Napoleon seizes power and almost immediately starts to show his corruption. It starts with the pigs taking the best food and escalates from there, through lies, gaslighting, and doublethink until eventually the revolutionaries become worse than the oppressors they overthrew. Throughout it all, you as the reader want to scream at the animals to wake up.

The game captures that underlying sense of not-quite-rightness with almost frightening accuracy. Worse, it makes you complicit. As the game goes on, you get choices for what the animals are to do; you can make them work or study, build defenses against the humans, or set birds to spread propaganda and surveil the farm. Each choice affects the world and characters to some degree, but you never fully know what those effects are. The rules are so opaque and the possibilities so diverse that after a single playthrough, even after four or five playthroughs, you are still getting unexpected and undesirable outcomes.

You know something is wrong — maybe you’re doing something wrong. You think you’re in control while also knowing full well that you’re not. It’s terror, brilliantly realized.

One of the things that makes Orwell’s Animal Farm so powerful is that it is built entirely upon that principle. As you play, as you try to manage the farm, you can only ever make things worse. Even if you manage the farm as well as possible — achieving the economic impossibility of having enough resources for everyone and more to spare — you wind up with the book’s ending of perverted idealism:

ALL ANIMALS ARE EQUAL BUT SOME ANIMALS ARE MORE EQUAL THAN OTHERS.

The alternative endings imagined by writer Emily Short may be less inventive but no less effective. They hammer home your abysmal failure with narrative closure. This isn’t a tycoon game debt spiral where you’re basically forced to give up. The ending can strike with the same opaqueness as any other decision. You know you’re running out of food, but how long will the game go on? Will it give you another chance to collect more? Or will the animals all simply starve?

In our interview about Orwell’s Animal Farm, Creative Director Imre Jele told me about another project he worked on, a horror game where he messed with the player’s expectations by changing button response times. This game doesn’t rely on those kinds of cheap tricks. Instead, it sets you loose with the best of intentions and challenges you to think about how those intentions can be co-opted and perverted to serve undesirable ends — how altruism can support oppression, how lies can be accepted as truth, and how you contribute to all of that. It’s terrifying.

And then you look up from the game.