Hitman 3 is a unicorn. It’s the kind of sequel that meaningfully shakes things up while successfully building upon the foundations of the past. For me, it does so by breaking the rules of its predecessors and adding a sense of structure to free-form play.

Stories have been an integral part of IO Interactive’s World of Assassination trilogy since the beginning, yet Hitman 3 takes a different approach — not just with more complex mission stories within the tapestry of each level, but by embedding narrative design cues to tell a tale about Agent 47 rather than just his victims.

Hitman 1 and 2 are all about execution in both meanings of the word: assassination and performance. Each level is a meticulous, intricate puzzle that you can put together in multiple ways. It’s engaging, yes, but the story never involves you. Those games use unapologetically old-school narrative design: cutscene, gameplay, and never the twain shall meet. Your success unlocks rather than contributes to new developments. You are a key to a door, nothing more.

That changes in Hitman 3. Granted, Hitman 3 is no bastion of narrative excellence. It does, however, demonstrate that even a little attention to storytelling can elevate an experience, and it makes effective use of gimmicks to get there.

Video game gimmicks are easy to hate. We’ve all come up against a frustrating ice level in a platformer or a poorly executed escort mission in an otherwise bolshy brawler. At their worst, they bring your fun to a grinding halt. At their best, the right gimmick at the right place can make magic. We remember Titanfall 2 and Dishonored 2 for the way their levels incorporated novelties that added to the core gameplay loops. A plane-shifted village in the former forces you to take advantage of the game’s tech-powered parkour mechanics, while the ability to play with time in both provides opportunities to approach the stimuli of enemies and traversal puzzles in four dimensions. Hitman 3’s gimmicks are not usually so integral to the identity of a level, but they serve much the same purpose: to freshen things up and move the story forward.

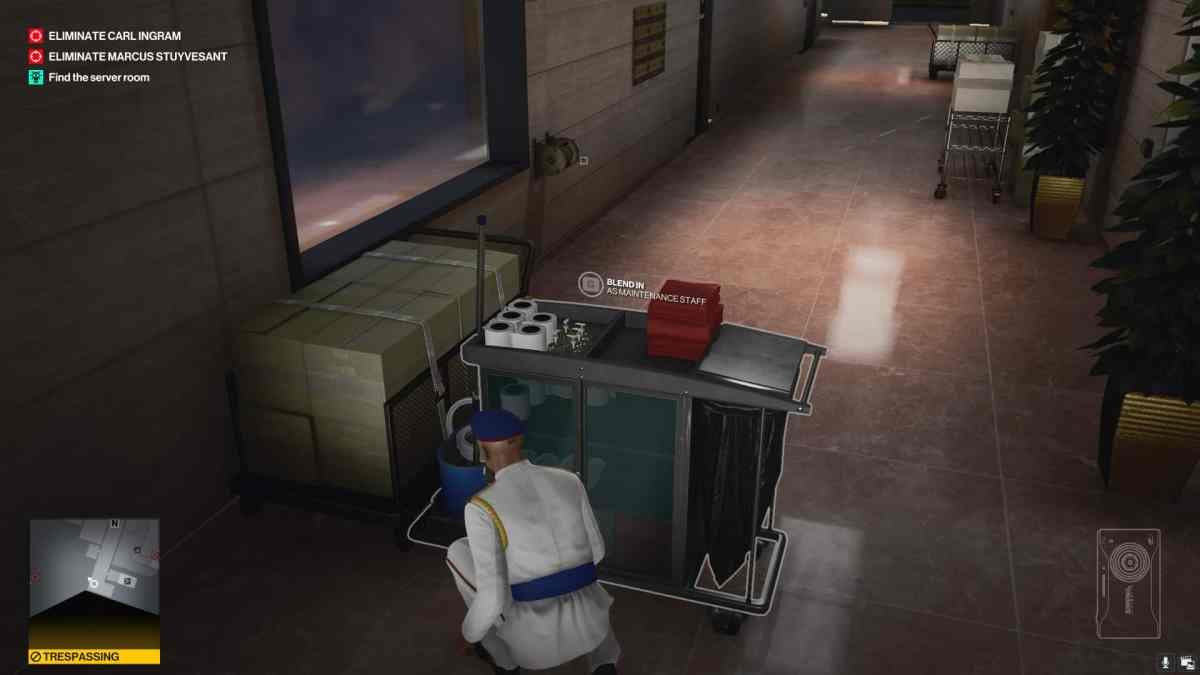

Thornbridge Manor is one example, leaning into the role-playing element of the series’s signature disguise-based stealth gameplay. You don’t need to impersonate the detective to complete the mission. If you do, though, you have a unique opportunity to talk to the manor’s residents, including dialogue choices. The storyline bends the gameplay rules established over the past five years, making you responsible for how the story moves forward in Hitman 3 rather than simply how you kill the target. That’s only a part of it, however.

47, Diana Burnwood, and Lucas Grey’s overarching goal to bring down Providence encroaches into your mission in a way that it never has before. It may be nothing more than a handful of messages over the radio, but it prepares you for what follows.

Meanwhile, the underground rave in Berlin will be nothing special for veterans of the highest difficulty setting, but it’s the first time in the World of Assassination trilogy that the rest of us genuinely become 47. For the first time, he is alone, his handlers absent, with no mission stories to guide your progress. You have to identify your enemies, determine unobtrusive assassination opportunities, and eliminate your targets without guidance. As with Dartmoor, the mission doesn’t break established rules, but it does embed narrative in them so that you can more readily embody 47 and understand why he is considered the best.

Similar twists on the series’s ethos crop up over and over. In one mission, it’s a scripted sequence that forces you into a traditional stealth approach; once upon a time, you could hardly swing a Sixaxis without hitting this kind of enforced linearity, but Hitman 3 deploys it for minutes rather than hours, ensuring it never becomes tiresome. Another mission completely reimagines the series’s level design to hasten the pace. Another, under the right conditions, incorporates a time limit, forcing you to adapt your plans on the fly.

Each of these gimmicks shifts the status quo to work wonders. They control and modify the pace in a gameplay experience usually given to methodical planning and execution. They keep you on your toes. They invest you in the story as it unfolds, without ever being intrusive enough to remove you from the experience.

More importantly, they make 47 into an agent. Rather than being just a tool of the ICA and the master of each domain, 47 — and you — must respond to events completely beyond your control. You are forced to react to evolving stimuli. You are part of the story.

I think I responded so strongly to IO’s revised approach because I made the mistake of playing the World of Assassination back to back. As brilliant as the earlier games undeniably are, the formula was wearing thin by the time I completed Hitman 2. There are only so many times you can scope out locations before you start to notice the repeated cues for electrocutions, accidents, poisonings, or explosions. Played piecemeal over months, it’s easy to imagine how the games would remain fresh and eminently replayable — less so when condensed into a couple of weeks. Needless to say, the focus on story in Hitman 3 came as a welcome surprise.

At the same time, it makes total sense from an overarching narrative design standpoint. The trilogy has been a process of drilling down into the story — as was planned from the very beginning, according to a 2016 interview with lead writer Michael Vogt: “We wanted to do a really ambitious storyline that would span several seasons and also build this ensemble cast. … Season 1 is the first act in a feature film. You know all the characters, you know the stakes, you know the dilemma, but it’s only getting started.”

The first game was about setting up the chessboard and establishing the main players. Hitman 2 delved deeper into the lore and slowly made the conflict more personal for the trio of lead characters. Hitman 3 is the logical continuation and conclusion of that process of story building. In being so, in changing the formula to force your hand at key points, it stands out as a statement piece in an industry where “bigger” still is considered better and attempts to waste your time are commonplace: Breaking the rules is a damn good thing, scope is more important than scale, and freedom is nothing without structure.