I visited Verdun for the first time with my family when I was a child. It would be the first of many visits, and it sparked a lifelong interest in the first World War that led to my co-creating a World War I FPS based around that pivotal battlefield on the Western Front. Our team did extensive research into the weapons, uniforms, battlefields, and accounts of the battles themselves to create something as authentic as possible. When we turned to making Tannenberg, a game set on the Eastern Front of World War I, we wanted to apply the same process to create a historically accurate game.

Luckily there is a wealth of information out there about the first World War. It was the first war to be widely photographed and even filmed — Peter Jackson’s incredible documentary They Shall Not Grow Old colorizes and restores old film footage to stunning effect. When planning, designing, and creating our maps, we generally used a collage of images to set the overall tone and highlight key features of the battlefield.

Of course it’s impossible to model every inch of ground fought over during World War I, and it would be even harder to do so on the Eastern Front where the distances involved were much greater. Instead, each map accurately represents the kind of landscape fought over within a larger sector of the war. This allows us to include terrain from across the entire Eastern Front in Tannenberg, from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea.

For example, here is our inspiration collage for the Dobrudja map we added to Tannenberg. When creating maps, we aren’t aiming to recreate specific battlefields — that wouldn’t be good for gameplay and would limit our ability to explore different aspects of the war. We do ensure that the individual details are accurate, including the fortifications, structures, trenches, and everything else right down to the mess tins and sandbags. We combine a range of sources from before, during, and after key battles to make a battlefield which is plausible and authentic. For Dobrudja, we wanted to include a view of the Danube, the distinctive wooden hilltop fortifications, and several artillery positions.

Personal accounts of battles in letters and military reports were also invaluable sources of information. One such example is the diary of Erwin Rommel, a young German lieutenant who would go on to become the infamous strategist known as the Desert Fox, who was forced to commit suicide after being implicated in the plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler. He saw action at Mount Cosna, which was the setting for one of our earlier maps. While we focused on his account of the fighting for Mount Cosna, other key aspects of the war in Romania, such as the oil derricks that were a vital strategic resource, were also included to give the map a more comprehensive feel. Descriptions of the terrain like this one below were very helpful to us:

“The avenues of approach were less favorable than I had thought. Bare grassy slopes in front and to the south offered no protection against hostile fire. The terrain seven to nine hundred yards north of the ridge road appeared more favorable. On the grassy slopes of the ridge leading to the Piciorul [River] numerous fairly large and dense clumps of bushes were scattered about. The Piciorul (652), located a mile north of the ridge road on the flank of the 5th Company was covered with large deciduous trees.

Sharp and dominating, the Mount Cosna summit loomed on the horizon in the rays of the rising sun. It was the objective for the attack on August 11. Would we be able to do it? We had to! My wounded arm was forgotten for I had six companies to lead against the enemy. I went about the difficult and responsible work with confidence and new strength.”

Reenactors are also a great source of information. They take historical accuracy very seriously and are often able to summarize research they’ve gathered from a range of places. This can be especially useful with things like uniforms, where simply looking at photographs often isn’t enough. Soldiers might not be wearing a proper regulation uniform, or they might not have been issued the latest gear. Attributions to the photo’s year, location, and even subject might be inaccurate or absent.

Reenactors are also likely to own genuine weapons or clothing which can be used as a reference for artwork and models, or even to record sounds from weapons. We worked with the C&Rsenal YouTube channel for details on many of the weapons in our games. This is of course the best way to get accurate sounds and to learn about any quirks of the weapons that may not appear obvious from photos or technical descriptions of their capabilities.

Naturally you have to be careful not to mix and match different versions of weapons. Even with a rifle as well known as the Russian Mosin-Nagant there were already three versions being used during World War I that had significant differences in length and other details. All three versions are featured in Tannenberg: the M1891, the M1891 Dragoon and the M1907 Carbine.

We ran into an unexpected challenge when searching for documentation from the Russian perspective. Many documents were lost or intentionally destroyed following the Russian Revolution. Even graveyards were levelled after the end of the war by the Bolshevik leadership, who wanted to center focus on the Revolution and discourage thinking that the war may have generated the conditions necessary for it to succeed. According to an article in the German news magazine Der Spiegel, there may only be a single gravestone left in Russia in memory of a soldier who fell during World War I.

This was a new challenge for us compared to our research for Verdun. You always need to take into account the perspective of sources, so even records from other countries describing Russian equipment or procedures have to be evaluated for accuracy. Even with the best of intentions, there may be errors in their recounting. Who can say how many irreplaceable historical records have been lost forever?

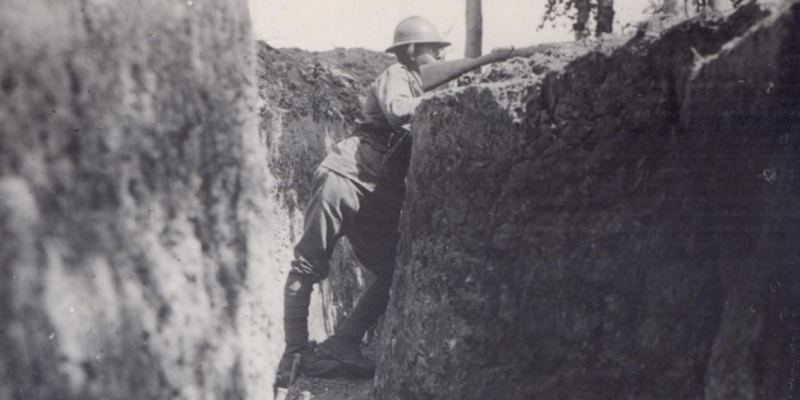

A photo of a Romanian soldier.

With Verdun and Tannenberg we wanted to create a game first and foremost, and so many realities of war are not recreated. We don’t simulate the small miseries and tedium of a soldier’s daily life during World War I, and we use artistic license to condense the key elements of huge theatres of battle into a series of carefully designed maps. They’re still large, but not to the scale that actual soldiers would have had to cope with! We also wanted to pay tribute to the people who died in the war by recreating what details we could as accurately as possible.

In the end, what you really notice is that for all the differences in battlefields, equipment, doctrine, language, political situation, and everything else, the soldiers themselves share many common bonds. The trenches they fought in may have been very different, but soldiers on the Western and Eastern Fronts would have shared many of the same challenges and experiences. It has now been more than a century since World War I ended. I’ll no doubt visit Verdun again, but for those who have never set foot on a World War I battlefield, we hope that our games can play a part in reminding people of a conflict that claimed so many lives and keeping the memory of those who fought alive for a little longer.