This review and discussion contains spoilers for Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is the sort of big, expansive pop spectacle that superhero movies should aspire to be. It is in tune with modern pop culture but also engaged with much deeper themes and ideas. Across the Spider-Verse is a sweeping epic that sends Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) journeying across multiple universes, but its multiverse framework is ultimately a mirror to the more mundane reality facing its protagonist.

Across the Spider-Verse is a coming-of-age story about Miles leaving the safety and security of the family home that he shares with his mother Rio (Luna Lauren Vélez) and his father Jefferson (Brian Tyree Henry). In his civilian identity, this is reflected in Miles’ plans for college — to leave Brooklyn to attend Princeton in New Jersey. As the superhero Spider-Man, it means confronting an interdimensional alliance of spider-themed superheroes.

This “elite strike force” is overseen by Miguel O’Hara (Oscar Isaac). O’Hara has structured his superheroes as something close to a police force. There is a rigid hierarchy, a careful recruitment process, and plenty of infrastructure. When Gwen Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld) is dispatched to Mumbattan, she’s put in contact with local operative Pavitr Prabhakar (Karan Soni). O’Hara’s headquarters is decorated with cells holding detained supercriminals.

O’Hara has taken it upon himself to protect the larger multiverse. He believes that the vast web of interconnected worlds is on the verge of collapse as a result of the accident at the collider in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. O’Hara believes that everything has its place and that it is his duty to maintain the established order. It is his responsibility to ensure that the boundaries that separate realities remain in place.

Jessica Drew (Issa Rae) and Miguel O Hara (Oscar Isaac) in Columbia Pictures and Sony Pictures Animations SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE.

Across the Spider-Verse is a love letter to comic books. Like Into the Spider-Verse, the movie opens with the logo of the Comics Code Authority. Like Into the Spider-Verse, it uses comic book covers as chapter breaks. The animation often employs a lot of the art style of comic books. While Into the Spider-Verse drew heavily from the interior artwork of Miles’ co-creator Sara Pichelli, Across the Spider-Verse draws a lot from the cover art of Spider-Gwen co-creator Robbi Rodriguez.

As such, O’Hara is framed according to the internal logic of comic books. He is a continuity cop. He maintains the canon, determining which events matter and which events don’t. Indeed, from his operations center, O’Hara monitors for “canon events” — narrative beats that are an essential part of any classic Spider-Man narrative: the spider bite, the death of an uncle, the warning that “with great power there must also come — great responsibility!”

This works in the postmodern context of the Spider-Verse films. These films are fundamentally about the question of what makes a Spider-Man story. They are also about who gets to be Spider-Man. Miles’ closing revelation in Into the Spider-Verse was that “anyone can wear the mask,” and so Across the Spider-Verse sets up O’Hara as a foil by putting him in a position where he declares that Miles is an aberration who “can never be part of this” larger Spider-Man concept, challenging Miles’ assertion. However, there’s more to it.

The multiverse is a common device in modern multimedia. Everything Everywhere All at Once won the Best Picture Oscar. Marvel projects like Loki and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness are built around the concept. Sony even employed it in its live-action Spider-Man: No Way Home movie. The CW staged a Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover with its DC properties. The Flash will find multiple cinematic universes colliding.

Gwen Stacy in Columbia Pictures and Sony Pictures Animations SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE.

While movies like Everything Everywhere All at Once can use the multiverse as a metaphor for bigger existential issues, there is a concern that many of these larger franchises are employing the concept as little more than a brand management tool. It can be a way to justify the nostalgic return of previous iterations of the same character or as a way of doing a soft reboot within the text of a franchise film. In short, the multiverse can often seem like a very abstract and very cynical concept.

Across the Spider-Verse uses the multiverse as more than just a postmodernist meditation on the concept of Spider-Man as an idea. Instead, the multiverse itself becomes a larger metaphor. At its core, Across the Spider-Verse is a film about the limits that exist on people’s ability to imagine a better world, as well as the compromises that people often accept as immutable laws. It’s about the structures and frameworks that people impose on reality as a way of justifying horrible sacrifices.

Miles is thrown into conflict with O’Hara when the veteran reveals that the new arrival will soon face a major “canon event.” Every Spider-Man faces the death of a close personal friend in the police force, often with the rank of captain. To underscore his point, O’Hara even plays footage from the climax of The Amazing Spider-Man as Peter (Andrew Garfield) cradles Captain George Stacy (Denis Leary). Miles realizes that his father, Jefferson, just received a promotion to the rank of captain in the NYPD.

It’s ostensibly a familiar abstract philosophical question: “the trolley problem.” It’s a choice between active complicity in one death or passive complicity in many more. O’Hara argues that the death of Jefferson will not only allow Miles to become the hero that he needs to be, but that it will prevent multiversal collapse. The “canon” must be preserved. However, this gets at the real philosophical argument that Across the Spider-Verse is making. The status quo comes at a high cost.

Spider-Man 2099 (Oscar Isaac) and Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) in Columbia Pictures and Sony Pictures Animations SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE.

Across the Spider-Verse is not subtle in its metaphors. As if to underscore the idea that the movie is about more than comic book fans arguing which events “count,” O’Hara’s organization calls itself “the Spider Society.” When Peter B. Parker (Jake Johnson) pulls Miles aside to explain that this is just “how stuff works,” they argue inside the mechanical clockwork gears and pistons of O’Hara’s Nueva York. This isn’t about continuity. It is about the shared understanding of how the world actually works, the engines that make it turn.

O’Hara is effectively operating a multidimensional police force, complete with jail cells and backup. The movie draws attention to the police metaphor, with both Miles and Gwen being the children of cops. At one point, during a heated confrontation with her father, another version of Captain Gwen Stacy (Shea Whigham), Gwen likens her mask to his badge. It feels deliberate that the film arrives in the midst of ongoing debates about the role of police forces in enforcing systemic injustice.

This might explain why the film’s most compelling and sympathetic new character is the anarchistic Spider-Punk (Daniel Kaluuya), who rebels against totalitarianism on his own world and is skeptical of O’Hara’s rhetoric in the multiverse. At the climax of the film, it’s Spider-Punk who helps Miles to escape from O’Hara and who ultimately opts out of O’Hara’s club. As reality collapses in Mumbattan, Spider-Punk wryly observes that it’s “a metaphor for capitalism.” He sees the horror of the system.

Of course, Across the Spider-Verse is hardly the first comic book adaptation to use the multiverse as a metaphor for the sort of moral compromises that underpin modern society. O’Hara is doing something very similar to the Time Variance Authority in Loki, maintaining the established status quo no matter how many sacrifices need to be made. However, Loki flubbed that metaphor in its first season finale, seemingly conflicted over whether dictatorship and child murder was really such a bad thing.

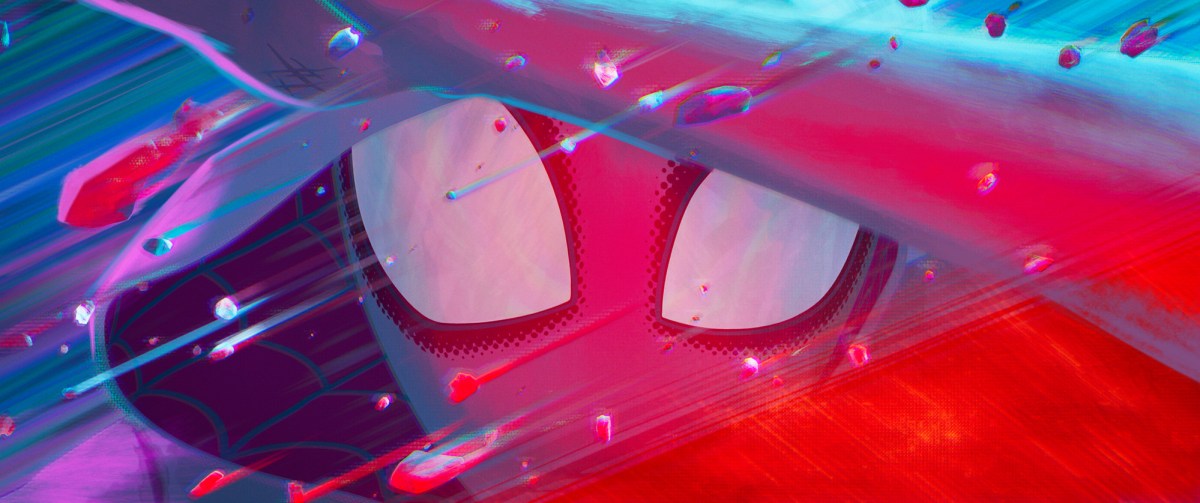

Miles Morales as Spider-Man (Shameik Moore) in Columbia Pictures and Sony Pictures Animations SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE.

It probably depends on which children pay that price. Miles Morales is a biracial teenager, the child of a Puerto Rican mother and an African American father. His mother admits that she’s afraid of what is waiting for him in the outside world. “You know, for years I’ve been taking care of this little boy,” Rio muses. “Making sure he is loved, that he feels like he belongs wherever he wants to be.” She confesses, “And what I worry about most is that they won’t look out for you like us.”

Across the Spider-Verse doesn’t bury its metaphor. Miles wears a prominent “Black Lives Matter” button on his backpack, a reminder of the disproportionate number of young African Americans who are the victims of systemic police violence. Gwen has a “Protect Trans Kids” poster in her room, a reminder that superheroes have long been stand-ins for queer groups. A scene where Miles tries to reveal his identity to Rio is framed as a teenager coming out to his mother about his authentic self, worried that she may stop loving him or that it might change everything. This is basic superhero stuff, but few modern superhero movies do it.

Indeed, even Rio’s warnings and pleadings to Miles, trying to alert him to the dangers that exist outside the safety of the family home, recall “the talk” that many African American parents have to give their children about dealing with the police. When Miles tells Spider-Punk that he comes from a loving home, Spider-Punk replies that it is a shame, “Because you’re not ready for everybody else.” In the film’s climactic action sequence, O’Hara pins Miles down and tells him that he is a “mistake” who doesn’t “belong” in this world.

Spider-Man (Shameik Moore) and Spider-Gwen (Hailee Steinfeld) in Columbia Pictures and Sony Pictures Animations SPIDER-MAN: ACROSS THE SPIDER-VERSE.

There is something radical about this, particularly in the larger context of superhero movies that treat their protagonists as paramilitary organizations or law enforcement. A lot of superhero films become facile power fantasies about the right of strong men to assert their will upon the world and dictate the shape of reality. Across the Spider-Verse rejects this. Gwen’s father breaks the cycle of death and loss by turning in his badge. At the same time, Gwen chooses to leave O’Hara’s Spider Society. The price of membership is too high.

In contrast to superhero power fantasies, Across the Spider-Verse is an empowerment fantasy. Miles is an outsider who looks at a broken system and refuses to buy in. In contrast, O’Hara argues that the suffering of innocents is a tragic but necessary web that holds society in place, “the connections that bind our lives together.” Even atop the multiverse, O’Hara cannot imagine any other possibility. It’s a bold statement about how deeply ingrained these systemic injustices are and how impossible it is for those in power to imagine alternatives.

With that in mind, it’s notable that one of the movie’s big recurring visual motifs — building on an iconic moment from the first film — is Miles’ ability to turn the world on its head, to look at the world upside down. Maybe it’s not the worst way to look at things. “Everybody keeps telling me how my story is supposed to go,” he warns O’Hara. “Nah, I’mma do my own thing.” In a world so broken, that’s true heroism.