“It’s not a lake. It’s an ocean.” That quote feels like a salient starting point for this piece because I feel I’ve barely scratched the surface of Alan Wake 2. One thing I’ve been very quickly reminded of, though, is that the writing of Alan Wake is extremely boring.

By that I mean the character, not the game (ergo the lack of italics). If you know anything about the series, you know that the fiction positions Alan Wake as a bestselling author with a legion of adoring fans. Alan Wake 2 adds in a deliciously mind-bending metanarrative where Alan uses his writing to escape from The Dark Place, a shadow realm where art can directly affect reality. It’s more than a stellar premise; it’s a perfect opportunity to showcase Alan’s talents, and the game does so by bringing back manuscript pages as both a collectible and recurring means of advancing the story. These pages are taken from Alan’s work-in-progress and…

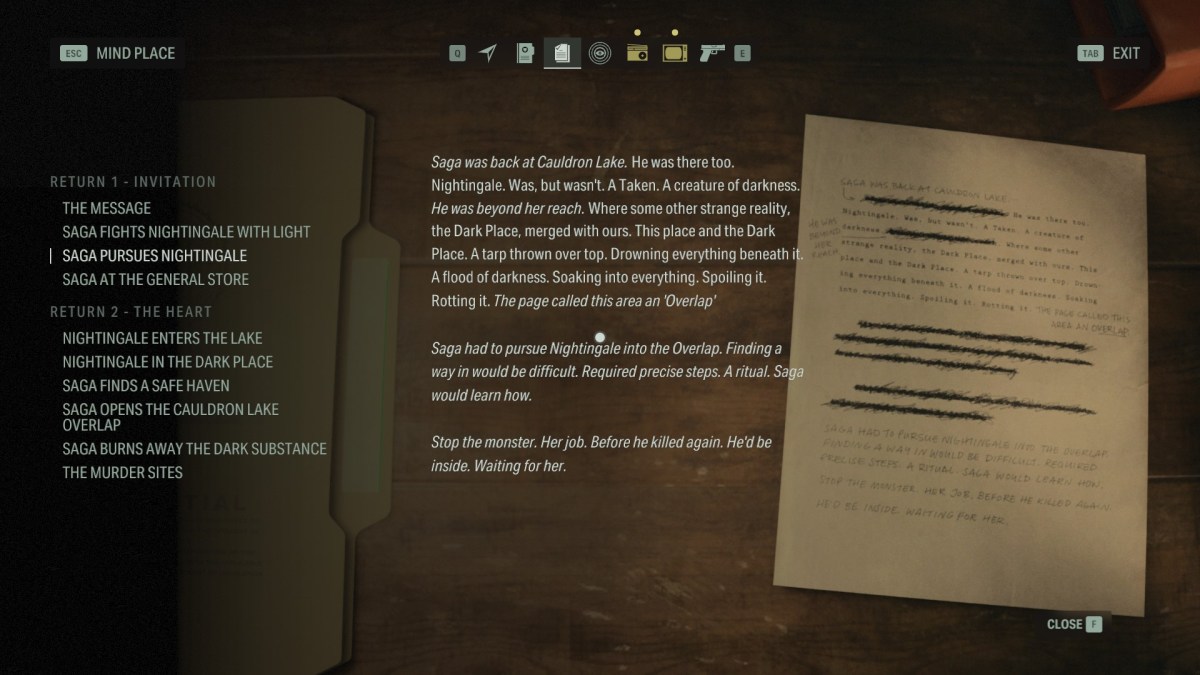

Okay, this might seem like me getting up on a wanky little soapbox and flexing my English degree, so let’s look at one of the first manuscript pages you find:

“Saga was back at Cauldron Lake. He was there too. Nightingale. Was, but wasn’t. A Taken. A creature of darkness. He was beyond her reach. Where some other strange reality, the Dark Place, merged with ours. This place and the Dark Place. A tarp thrown over the top. Drowning everything beneath it. A flood of darkness. Soaking into everything. Spoiling it. Rotting it.”

Related: Do You Need to Play Alan Wake 1 & Control Before Alan Wake 2?

It’s awash in short, simple sentences — often using sentence fragments. Nor is this an isolated example; it’s a demonstration of Alan’s norm. He struggles to put more than six words in any single sentence — as if he’s writing for a middle-grade readership.

Maybe that’s a little harsh. Short sentences (and sentence fragments) absolutely have a place in writing. I opened this article with two in a row — an Alan Wake quote, no less. At the end of a paragraph or a piece, they can act as a powerful punctuation point, cutting through the noise that preceded them. Between long sentences, they break up the flow, giving the reader a brief chance to reorient themselves and breathe. Deployed sequentially, they can ratchet up the pace and tension, creating a potent sense of immediacy. Alan Wake is clearly aiming for the last.

After all, he’s a writer of pulp thrillers. He’s not trying to lure readers in with lyricism and evocative, transportive imagery. He’s not trying to be a Charles Dickens or a Trent Dalton or a David Mitchell. His contemporaries are the likes of Lee Child and Dan Brown, which (meaning no disrespect because their books are gripping and extremely popular) is a pretty low bar in terms of the technical qualities of their writing. Alan Wake doesn’t come close to matching them, though. What we see of his work barely deserves to be called a first draft. It’s nothing more than a brain dump of unformed ideas tossed willy-nilly onto the page and shaped into something vaguely resembling a narrative.

The problem isn’t his use of short, ill-formed sentences; it’s his indiscriminate overuse of them. He tosses them around like seeds in an aviary, completely oblivious to the effect on pacing or reader engagement. And, to be completely fair, there’s a reason for it within the context of Alan Wake 2 being a game: you’re not actually meant to read them. As a player, you’re supposed to listen to them within the live-action videos over which they’re played. There, we hear voice actor Matthew Porretta’s stellar interpretation, disjointed, rapid fire; there, it’s much more interesting, even if I still wouldn’t call it compelling.

But, because the manuscript pages often provide clues, I doubt most players are going to bother rewatching the videos over and over again. Instead, they’ll read the transcripts, hunting for the keywords and the signposts for what to do next, and so the weakness of Alan’s writing is cast under the spotlight — and found wanting.

And maybe that won’t actually be a problem for most players. Maybe most people will chalk it up to the quirks of the decision to put writing front and center of a video game, where keeping players engaged is the core challenge. We’re obviously not meant to read the manuscript pages as if they actually are a novel… but I still can’t help but do so. I imagine trying to read three or four hundred pages of this broken claptrap. By the end of it, I’m pretty sure my brain would be as broken as Alan’s because it’s just so damn dull.