Aliens was released 35 years ago this month, and it remains one of the best sequels ever made.

Alien was a masterpiece of science fiction horror. In their original Sneak Previews discussion of it, critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert correctly zeroed in on the film’s strengths: It was essentially “the haunted house film” transposed into space. It is now something of a cliché to return to Siskel’s original description of Alien as a “haunted house movie” or even a “haunted house in space,” but familiarity has rendered the observation no less accurate.

Aliens doesn’t fall into the trap of so many horror sequels — the tendency to take the same basic structure and apply it to new environments like a psychiatric institution, “Manhattan,” or “the Hood” to diminishing returns. The Alien vs. Predator spinoff films would eventually fall into this template, with Requiem sending its monsters to terrorize a small town. It’s the Alien franchise’s equivalent of sending Jason (Kane Hodder) to space.

Aliens avoids repeating the formula that worked so effectively in Alien. James Cameron had been warned that competing with Ridley Scott’s Alien would be “a no-win scenario,” so he decided to push the sequel towards his own strengths as a filmmaker by shifting it away from horror and towards action. Cameron would boast, “If the first film is a haunted house, then the second film is more of a roller coaster.”

If the original Alien played like a tension-filled slasher movie about monsters hiding in the darkness, then Aliens was a bombastic action movie about an overwhelming enemy. Cameron famously wrote the first draft of Rambo: First Blood Part II while he was working on the script for Aliens. The two inevitably informed one another. “This time it’s war,” boasted Aliens’ theatrical poster. Cameron’s dialogue was shaped by “how soldiers talked in Vietnam.”

Like Star Wars — another science fiction franchise shaped by the Vietnam experience — Aliens finds a technologically superior force pitted against a seemingly tactically inferior enemy. A lot of the imagery in Aliens directly invokes the popular memory of Vietnam, such as the flamethrowers and the personalized armor. The cast included veteran marine Al Matthews as Apone, who conceded that filming brought back his “Vietnam syndrome.”

However, there was more to Aliens’ success than approaching the world of Alien from a fresh angle. Cameron clearly admired and respected Alien, but he was never unduly beholden to it. Like many of the very best sequels, Aliens exists both in conversation with and in opposition to Alien. It offers a challenge to the original film, deliberately and pointedly inverting its core themes.

Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) is one of the most enduring and influential characters in American science fiction. Weaver would earn a “dark horse” Best Actress Oscar nomination for her work on Aliens. Ripley has been described as “the first action heroine” and “a feminist icon.” However, what’s interesting about the Alien franchise is that the films offer very different and occasionally mutually exclusive arguments for what makes Ripley so successful as a feminist action hero.

Alien is a horror movie built around gendered fears. The eponymous monster is a collection of weird sexual nightmares conjured into being by H.R. Giger. The design of the creature itself is explicitly phallic, with its monstrous head and its protruding mouth — not to mention its tendency to impale victims on its tail. However, the creature’s reproductive cycle involves an attack by the facehuggers, which look like “a nightmare vagina” and implant embryos inside the throat of their victims.

The threat posed by the xenomorph is explicitly sexual. “It uses its victims as a host,” explained Alien writer Dan O’Bannon. “It rapes them. Then they give birth. This is what makes it so disturbing.” However, unlike most slasher movies, that penetrative violence is not directed primarily at women. Kane (John Hurt) is the first victim of the monster, impregnated by a facehugger. In a deleted scene, Dallas (Tom Skeritt) and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton) are turned into eggs.

O’Bannon was very clear on what he was doing. “I’m not going to go after the women in the audience,” he would recall telling the producers. “I’m going to attack the men. I am going to put in every image I can think of to make the men in the audience cross their legs.” As such, it’s notable that Ripley is the only survivor of this attack. She is one of the only two women on the ship, along with Lambert (Veronica Cartwright).

Ripley ended up a female character entirely by accident. The protagonist’s gender was famously only chosen late in the development process, with the script explicitly written to avoid gendering the primary cast. With this in mind, Ripley largely survives Alien by virtue of avoiding explicitly gendered behavior. Ripley is clearly contrasted with Lambert, the last crew member to die. Lambert is consistently presented as much more emotional than Ripley — an established (if not necessarily correct) shorthand for female coding.

When the facehugger attaches itself to Kane, Ripley refuses to let her emotions cloud her judgment. She insists on properly quarantining the team and refuses to allow the specimen onto the ship, although she is undermined by Ash (Ian Holm). In a scene included in the director’s cut, Lambert attacks Ripley for that lack of sentiment. “You bitch!” she protests. “You were gonna leave us out there!” Lambert clearly believes there’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.

The deleted scenes from Alien included more sex, but in the finished film that sexuality is repressed and sublimated. A conversation between Ripley and Lambert suggests that the mysterious Ash has never displayed any sexual interest in either. However, his climactic assault on Ripley takes on a decidedly sexual subtext as he tries to cram a rolled up porn magazine down her throat before exploding in a mess of white fluid and revealing himself as the franchise’s first messed up android.

Ripley allows herself to be conventionally feminine towards the climax of the film, after the rest of the crew is dead. She strips out of her unisex jumpsuit and into her underwear and makes the emotional decision to return for the cat Jonesy. This throws Ripley into direct conflict with the xenomorph. Between the climax and Ash’s assault, Alien only really presents Ripley in a feminine context when she comes under attack.

Aliens offers a different approach to the theme of gender and sexuality. While Ripley survived by rejecting conventional femininity in Alien, she instead embraces it in Aliens. Aliens retroactively reveals that Ripley was a mother, although her daughter died before she was discovered floating in space. When the human colony on LV-426 is attacked by the xenomorphs, Ripley is convinced to return to the planet with a platoon of space marines to eliminate the infestation.

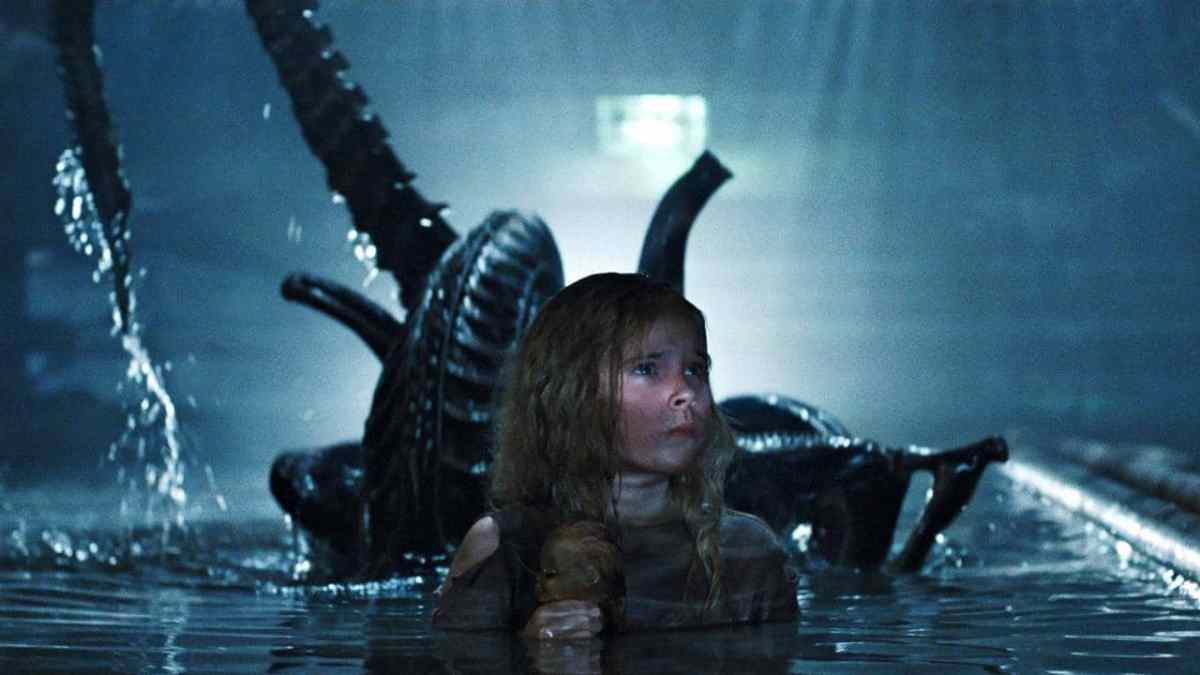

The marines discover an orphan named Newt (Carrie Henn) that Ripley adopts as her own. Ripley also strikes a bond with Corporal Hicks (Michael Biehn), and the three characters come to form an unlikely surrogate nuclear family that is implicitly a replacement for the family the xenomorph took from her. As if to underscore this point, the heroes defeat the monsters by detonating the fusion-powered atmosphere processing station in a literal nuclear explosion.

Aliens is largely about Ripley dealing with the trauma of the first film, and she does this by embracing a more conventional form of femininity. Cameron even lightly reworks the xenomorph threat to reinforce these themes, replacing the egg conversion from the deleted scene in Alien with the Alien Queen as a literal monstrous mother. The climax of Aliens becomes two competing versions of femininity, with Ripley’s “good” mother defeating and vanquishing the warped “bad” mother.

This is a recurring motif in James Cameron’s films. After all, The Terminator is arguably a subtly subversive slasher movie where the heroes win precisely because the female lead breaks with the conventions of the genre and has sex. In both The Terminator and Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) is largely defined by her role as mother to the messiah, something that Terminator: Dark Fate wryly acknowledges by having Sarah call herself “the womb.”

It is possible to overstate this argument. Ripley might form a recognizable surrogate family unit with Hicks and Newt, but it’s notable that the conventional gender roles are reversed. Hicks is very much the damsel in distress, presented as vulnerable and passive. He is largely out of action for most of the climax. Similarly, the film skewers the hypermasculinity of the marines, notably through the posturing of Hudson (Bill Paxton) and even Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein).

Both Alien and Aliens explore what it means for Ripley to be a female action hero, although they ultimately settle on very different approaches to the same idea. In Alien, Ripley survives the monstrous xenomorph by rejecting the gender-coding that would present her as maternal or feminine. In Aliens, Ripley only truly vanquishes the alien menace by embracing gender conventions like motherhood and a reasonably conventional family unit.

Neither approach is inherently correct or incorrect. It’s possible to make an argument for both, that Ripley should not have to conform to gender stereotypes to be considered a feminist hero but also that it’s possible for Ripley to embody certain stereotypical aspects of femininity while still being an icon. It’s a conversation, and both Alien and Aliens are enriched by the perspective that the other brings. (The much underrated Alien 3 brings its own distinct point of view to the table.)

This is what makes Aliens such a great sequel. It doesn’t repeat Alien. It engages with it.