This article contains spoilers for the first four episodes of Andor on Disney+ in its discussion of parallels with film and TV production and Star Wars fans’ relationship with the franchise.

In this week’s episode of Andor, there is a charged conversation between Luthen Rael (Stellan Skarsgård) and Vel Sartha (Faye Marsay) about the future of their shared enterprise. “We need this to work, Vel,” Luthen warns his younger colleague. “Failure would be devastating.” He emphasizes, “This has to be a win, Vel.” In the context of the episode, Luthen is talking about a daring heist on an Imperial facility. However, it occasionally feels like he is talking about Andor itself.

A lot of modern pop culture has grown increasingly insular and self-aware. As these franchises grow larger and more expansive, they often find themselves grappling with the weight of their own legacy. This is why shows from Star Trek: Strange New Worlds to Ms. Marvel are effectively about modeling fandom for the audience. As these franchises become more ubiquitous, they also inevitably become about themselves.

Andor is a show about a lot of different things. It is a show that asks what it means to be Star Wars in the modern world, an exploration of the folly of empire, and a collection of showrunner Tony Gilroy’s pet fascinations with the public sector and overzealous mid-level bureaucrats. However, watching Andor, it often seems like the show is also about Star Wars as a franchise. More than that, it is a show about what it means to try to love Star Wars as a franchise in its current state.

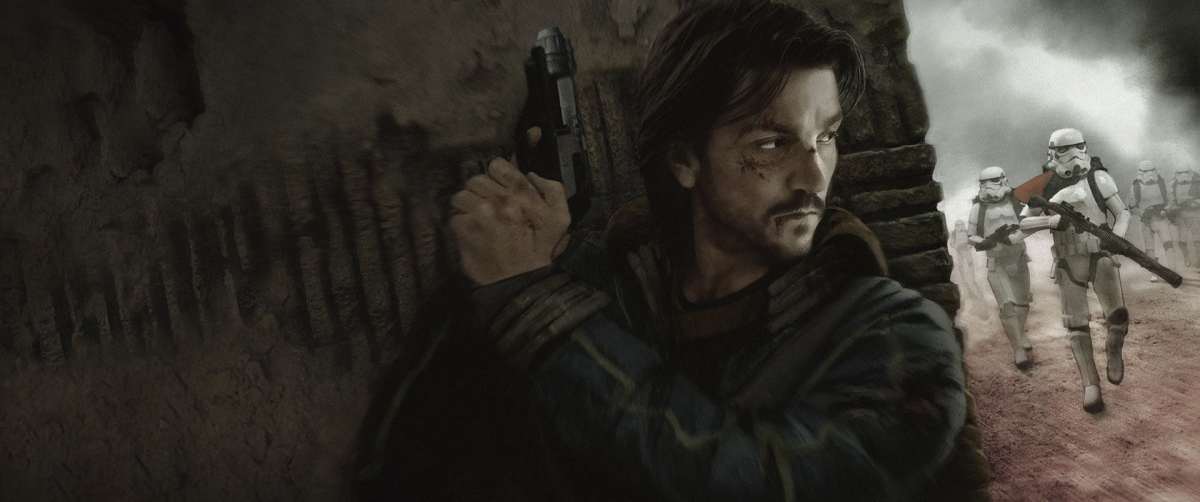

Luthen and Vel are organizing a terrorist strike. However, it also sounds like they are trying to film a Star Wars movie or television show. Luthen arrives at his meeting with Vel to inform her that plans have changed suddenly. She will have to take Cassian Andor (Diego Luna) onboard. Vel is understandably frustrated at the last-minute changes being made to a complex operation. “Now?” she protests. “Like this? Five months in? Just plug in some new person?”

The Star Wars franchise has been a mess since the release of The Last Jedi, with almost every project undergoing some sort of creative upheaval. Phil Lord and Christopher Miller were fired from Solo: A Star Wars Story quite late in the process, to the point that large portions of that movie had to be reshot by Ron Howard. Director Colin Trevorrow departed the movie that would become The Rise of Skywalker shortly before it entered production and was replaced at the eleventh hour by J.J. Abrams.

These were the films that made it into cinemas. Josh Trank’s Boba Fett was canceled before it entered production, although the studio would develop The Book of Boba Fett as a streaming series. More recently, Patty Jenkins’ Rogue Squadron was removed from the production slate. The streaming shows have also faced similar problems. Oscar-nominated screenwriter Hossein Amini was replaced on Obi-Wan Kenobi because his sensibilities didn’t match the optimism Disney wanted.

Andor showrunner Tony Gilroy knows firsthand how chaotic the production of Star Wars media can be. Gilroy reportedly replaced Rogue One director Gareth Evans during major reshoots of that movie’s third act, ghost-directing the film’s climax. Ironically, Gilroy had a similar experience on Andor, albeit much earlier in the creative process. Stephen Schiff was originally announced as showrunner for Andor in November 2018, with Gilroy replacing him in April 2020.

According to Warren Beatty, director George Stevens used to say making a movie was like going to war. Watching Andor, it often seems like the inverse is also true. The show returns to the imagery of movie production repeatedly. On his way back to Coruscant, Luthen dons a distinctive wig and practices his poses in front of a mirror. As Vel explains the plan for the raid to Cassian, Karis Nemik (Alex Lawther) points out the care that he took in making the models for that presentation.

Narratively, Andor is effectively the story of Cassian coming to believe in something greater than himself. Luthen recognizes great potential in the disillusioned and disaffected young man and seeks to recruit him to the cause. “Wouldn’t you rather give it all at once to something real than carve off useless pieces till there’s nothing left?” Luthen challenges Cassian. Inevitably, given where Rogue One finds Cassian, the character must eventually become a true believer.

However, if Andor sometimes plays as a documentary of its own production, Cassian’s journey also feels like the story of somebody learning to love Star Wars. Luthen is drawing Cassian into the world of Star Wars and asking him to invest in it. He is asking Cassian to abandon his weariness and cynicism and to believe in the magic of something greater than himself. Within the world of the show, that is the idea of rebellion. However, it often feels like it is also the idea of Star Wars itself.

There are maybe some autobiographical shades to this, even beyond Cassian’s arrival into a project that was already underway. Vel is shocked to discover that Cassian is “a mercenary,” a literal “gun for hire.” Luthen assures her, “I’m paying him.” Cassian’s ambivalence towards the project perhaps mirrors Gilroy’s original lack of enthusiasm for Star Wars. By his own account, Gilroy was “never interested” in the franchise before working on Rogue One and is still “not a fan fan” of the property.

This is not a bad thing. After all, Nicholas Meyer was no fan of Star Trek when he made The Wrath of Khan. More to the point, Gilroy seems aware of the fact that Andor needs to do more than rely on the audience’s assumed familiarity with and affection for Star Wars. In Gilroy’s own words, Andor is a show that is aimed at the “Star Wars hesitant, or Star Wars averse, or Star Wars reluctant.” It understands that it has to make a case for Star Wars.

There is perhaps a concession here that Star Wars is not what it once was. The franchise’s value has been diluted and undermined by both the volume and the quality of releases in recent years. The second season of The Mandalorian was just an advertisement for Disney+’s library and slate. The Book of Boba Fett was just shapeless “content soup.” Obi-Wan Kenobi lacked anything resembling a point of view or perspective. Even the Star Wars faithful might feel as disillusioned as Andor.

Andor acknowledges this in its own way. During the briefing, Lieutenant Gorn (Sule Rimi) explains that the heist will take place during a religious celebration for the indigenous Aldhani population. A rare stellar phenomenon creates a spectacular light show, opening “the window to the galaxy.” The implication seems to be that it is an event similar to the Aki-Aki Festival of the Ancestors as featured in The Rise of Skywalker. It is a celebratory spectacle and a metaphor for Star Wars itself.

However, Gorn warns Cassian to manage his expectations. “It’s not the event it used to be,” he states. Andor’s spectacle is decidedly smaller and less self-congratulatory than the comparable event in The Rise of Skywalker. Of course, that doesn’t mean that the festival is any easier a production. “From the ground, it’s a thing of beauty,” Nemik advises Cassian. “In the air, it’s chaos.” Again, it sounds very much like he’s talking about what it’s like trying to make a Star Wars film.

Still, Andor finds some romance in Star Wars, even as it acknowledges that the franchise is not the event it used to be. On returning to Coruscant, Luthen welcomes Mon Mothma (Genevieve O’Reilly) to the antiques store that he operates as a front for his rebel activity. Again, the metaphor is not subtle. Luthen is peddling artifacts that are perhaps relics of a bygone era, things that have inevitably declined and deteriorated from their glory days.

Nevertheless, Luthen makes an argument for the mythic power of this pantomime. “Free your mind, Senator,” he advises her. “This is a place where time stands still. It’s hard being surrounded by this much history and not be humbled by the insignificance of our daily anxieties.” Again, it is a moment that arguably makes more sense when considering Star Wars as a cultural artifact. Luthen rolls up his sleeves and gets his hands dirty on location, but he can sell the polished fantasy with the best of them.

Ultimately, after five years of somewhat underwhelming Star Wars media, it takes a genuine act of faith to believe in Star Wars again. Part of what is so compelling about Andor is that the show is honest and open about this. The series is written in such a way that Andor’s inevitable leap of faith towards what will become the Rebel Alliance is paralleled with the viewer’s leap of faith in trusting a piece of Star Wars to be good again. Gilroy is asking a lot of his audience, but he doesn’t hide that.

It will take a lot to win Cassian over, just as it might take a lot to reassure fans burned out on Solo, The Rise of Skywalker, The Mandalorian, The Book of Boba Fett, and Obi-Wan Kenobi. Still, there is hope. When Vel’s team argues about accepting Cassian on this mission, it is Nemik who speaks up for the new arrival. “He’s committed,” Nemik states. “I’m feeling that. I want to.” When asked what he is feeling, he explains, “His belief in the cause. When it comes down to it, that’s all I need to know.”

In Rogue One, Jyn Erso (Felicity Jones) argues that “rebellions are built on hope.” Maybe good Star Wars is too.