Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss is often considered one of the first examples of immersive sims, games focused on player agency and complex gameplay that emerges out of the interaction of multiple simpler systems. So it is perhaps little wonder that the first title developed by Arkane Studios — the primary torchbearers of the immersive sim philosophy since the demise of the likes of Irrational Games — was a spiritual successor to Ultima Underworld.

As Dishonored is to Thief and Prey to System Shock, so Arx Fatalis is to Ultima Underworld. Indeed, Arx Fatalis was originally conceived as a direct sequel to Ultima Underworld II but ended up its own thing due to licensing issues. Twenty years later, particularly with the weight of Arkane’s increasingly polished back catalogue behind it, it is difficult to take a balanced look at Arx. On one hand, it remains unmatched for its staggering ambition, innovation, and atmosphere — a proof of concept for many of the ideas Arkane went on to refine in subsequent years. On the other, its internal rules, controls, and balancing are infuriatingly inconsistent.

Arx’s biggest draws are its attempt to simulate a real, breathing world and its magic system. Light a torch, throw it at some logs, and it will kindle a flame. Use the flame to cook raw food or bake bread, which can then be eaten to regain health. Find a mortar and pestle and you can use it to grind up herbs. Drink some wine and you can put the ground powder into the empty bottle, then heat it in an alembic to create a potion or a poison. Interactions like this might not seem especially novel or complex in 2022, particularly in the wake of the wonderfully reactive Divinity: Original Sin titles, but they pushed the envelope in 2002. There is a thrill to looking around the world and your inventory and wondering how they might be combined.

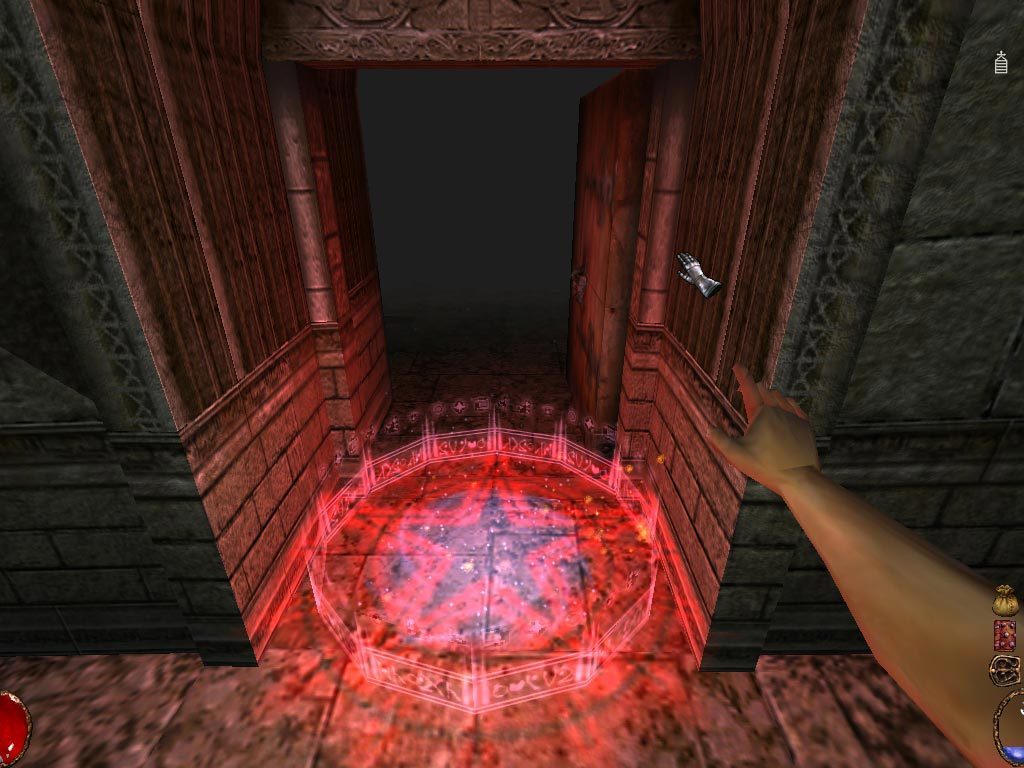

Meanwhile, the magic system in Arx Fatalis tries to capture a sense of genuine spellcasting by requiring the player to learn runes, which must then be drawn with the mouse and combined to invoke different spells. For instance, a line drawn from left to right followed by right-down-right casts a series of magic missiles. Up to three spells can be precast and mapped to hotkeys for a quick invocation in the heat of battle. As a result, sorcery feels tactile and involved — a kind of first-person interpretation of 8-bit- and 16-bit-era cheat codes. Like learning those codes, the magic system demands investment, first to memorize various rune combinations and then to practice their casting until it becomes second nature.

The world itself is a dungeon set in a “Dying Earth” universe. It’s a premise that has become more popular in recent years but that remains on the fringes of fantasy and science fiction — underexplored and with plenty of opportunities for unusual storytelling.

Arx’s sun has faded and its races — humans, goblins, trolls, dwarves, rat-men, snake people, and others — have been driven underground away from the inhospitably cold surface. They occupy various levels of a vast network of caverns and continue with their old politics and schemes. It’s a dark, oppressive, and at times overbearingly claustrophobic place underpinned by some of the period’s best sound design. Chainmail echoes through stony corridors and against metal grids, underground streams churn and gurgle, and vents howl and rattle as they draw fresh air in from the icy surface.

And yet, for all that, these elements frequently fail to come together. The emphasis in Arx Fatalis on a simulated world provides opportunities for interesting combinations, but just as often the game doesn’t do enough to telegraph its full repertoire of rules. An early quest, for example, requires the player to find a stolen idol. There are narrative clues to identify the thief and his key, but not to find the lock that the key unlocks. As a result, completing the quest can be a frustrating exercise in trying the key on every locked door and chest in the vicinity.

In fact, many of Arx’s interactions reduce to point-and-click trial and error as you select an item in your inventory and then click the cursor on random bits of the world to see if it responds. Can you bash open a wooden door? As it happens, you might not be strong enough. But unlike in the aforementioned Original Sin titles, neither can you set the door on fire or destroy it with magic. Your torch, for example, which can be used to light fires, inexplicably cannot be equipped as a weapon.

These frustrations are compounded by Arx’s controls, a Frankensteinian mix of three different schemes that often feel more like playing a flight simulator than an RPG. The movement scheme allows you to look around, walk, jump, crouch, attack, and engage in basic interactions with items. But if you’d like to pick anything up or attempt a more sophisticated interaction, you must tap a button to switch over to another set of controls.

Meanwhile, in order to cast spells, you have to hold yet another button to bring up a third UI that allows you to freely draw runes. The controls are reminiscent of System Shock 2, but they felt quaint in 2002 and feel antique in 2022. Faced with multiple enemies, navigating between the three overlays can be completely overwhelming, especially if you’ve made the wrong choices in Arx Fatalis’ RPG system.

This system allows you to invest points into a series of stats at the start of the game and upon leveling up, to chat and trade with NPCs, as well as to manage your quest log and your inventory. They are familiar genre staples, but they don’t offer the sort of flexibility seen in Arx’s RPG contemporaries, like Morrowind or Neverwinter Nights. Put too many points into anything other than stealth or close-quarters combat at the start of the game, for example, and you will be faced with a miserably difficult first few hours. Despite the in-depth rune system, the game does not cater to spell-casters until well into its second act, nor does it care if you can pick locks or disarm traps if you aren’t able to sneak or defend yourself. And with just 10 experience point levels across the entire game, character progression feels slow and unrewarding.

At times, Arx Fatalis seems like it’s crying out for the modern obsession with objective markers, mini-maps, quest summaries, codices, hints, and tutorials — something to tie its ideas together and better guide the player through its dense systems. At other times, however, it feels like a collection of grand experiments that could not hang together even with the most egregious hand-holding.

Despite all that, it’s difficult not to be fascinated by Arx Fatalis. Its attempt to craft an unconventional and demanding game on the foundations laid by Ultima Underworld serves as a manifesto for everything that Arkane Studios has done since. The emphasis on player trust and agency, simulation, and rich world-building is present in every title.

Dark Messiah of Might and Magic iterated Arx’s combat and magic, and Dishonored refined it further still, leading to outrageous gameplay opportunities. Prey offers sophisticated object interactions in the form of item mimicry, recyclers that can break down almost anything in the world, constructors that can build any inventory item, and the GLOO Cannon, which can be used to temporarily rewrite the way levels function and the routes they offer. Meanwhile, Deathloop found a way to package its quests and set pieces into a single, evolving, narratively coherent whole. In that sense, even if the various parts of Arx Fatalis don’t always come together, they have found their way into every game Arkane has made since.