This article contains full spoilers for the Barry series finale, “wow.”

Barry was always a show about the lies that people tell.

At its core, Barry was a show about acting, a profession that Marlon Brando described as “lying for a living.” In some ways, that is exactly what contract killer Barry Berkman (Bill Hader) was doing. A veteran of the Afghanistan War, Barry became a murderer for hire on his return home. However, during a job in Los Angeles, Barry stumbled into an acting class and found himself transformed. The chance to be somebody else and to reinvent himself was appealing.

It is easy to understand why Berkman was drawn to performance. In that first episode, acting teacher Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler) declares that “acting is truth,” but it is also a way to lie to oneself. Barry believed that he could start a new life in Hollywood. “The main character is us(;) that’s the audience surrogate,” explained Hader, who co-created the show. “He’s lying to himself on this big thing, but hopefully it’s a thing that can be really relatable to people.”

Over the course of its four seasons, Barry returns to the idea that an individual cannot escape their past. Everybody in Barry tries to rewrite their own history, convinced that they deserve a good life and that reality should not serve as a roadblock on that journey to self-fulfillment. Barry continues to believe this even after he is arrested at the end of the third season, spending most of his time in prison clinging to the hope of a new life in the witness protection program.

Although that scheme doesn’t work out, Berkman eventually escapes from prison. He absconds across the country with his lover Sally Reed (Sarah Goldberg), starting a new life in the desert. Barry jumps forward eight years in the middle of the season, revealing that Barry and Sally have managed to craft a life together in anonymity. They have even had a son together, John (Zachary Golinger). However, that life is built on a fragile foundation. It seems like it could collapse at any moment.

In the end, Hollywood brings it all crashing down. Discovering that Warner Bros. is planning an adaptation of Barry’s crimes, Gene Cousineau comes out of seclusion. He tries to center himself within the narrative that is being constructed. Sensing that such a high-profile project could bring his house of cards tumbling down, Barry journeys to Los Angeles to murder his former acting teacher. Sally and John wait behind, but Sally has a breakdown and the pair follow Barry to Los Angeles.

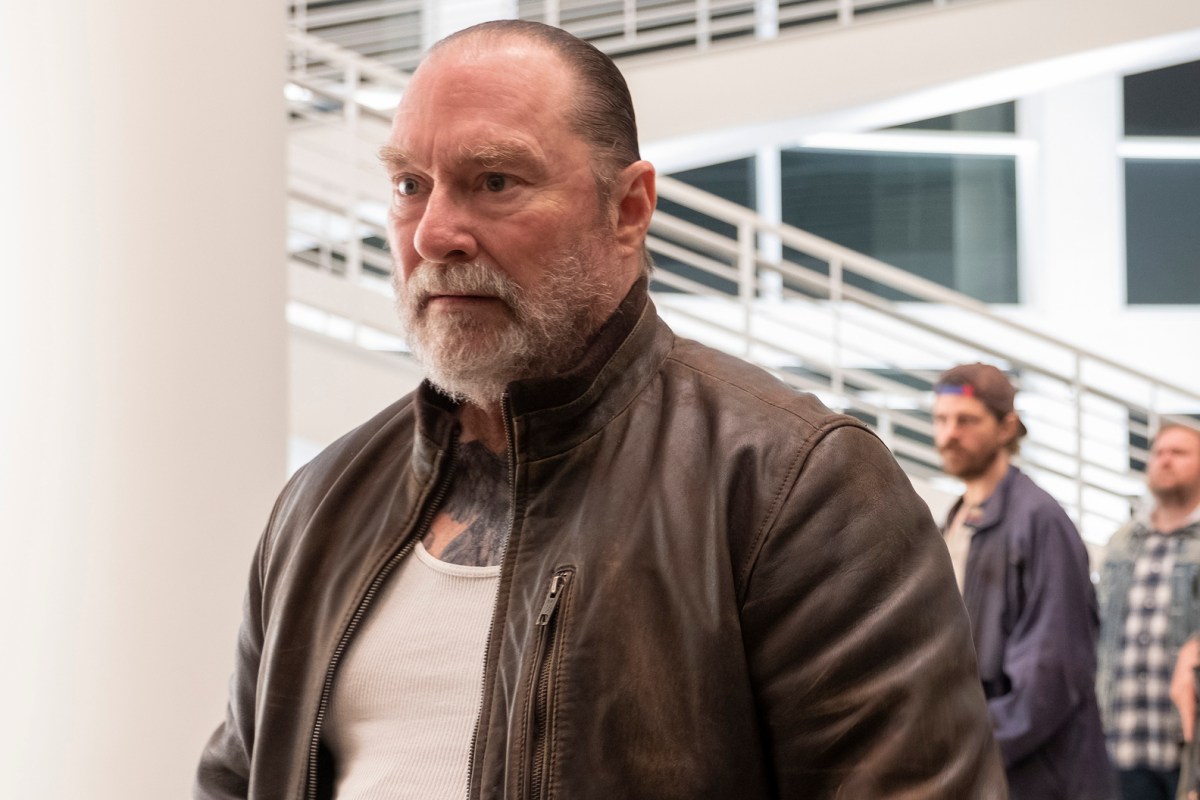

Because the past is never truly buried, even in the show’s stark desert vistas, Barry’s return provides an opportunity for some old enemies to settle their own scores. Barry’s former handler, Fuches (Stephen Root), has just been released from prison and wants to avenge himself on the surrogate son who left him to rot. Fuches finds himself in a heated standoff with Chechnyan mobster “NoHo” Hank (Anthony Carrigan) who believes he can appease Fuches by offering up Barry on a platter.

Hank’s criminal empire is built on its own set of lies. To secure his position at the head of the mob, Hank was complicit in the murder of the love of his life, Cristobal (Michael Irby). However, Hank has been unwilling to admit that. In the eight years since Cristobal’s death, Hank has built his criminal empire as a monument to his long-lost lover. The organization is named “Nohobal,” a portmanteau of their names. A gold statue of Cristobal stands in the lobby of Hank’s building.

Nobody on Barry can let go of past grievances. More than that, nobody on Barry can properly own up to their past wrongs. At one point in the show’s penultimate episode, Sally considers turning herself and her son into the police, but a traumatic flashback holds her back at the last minute, allowing Hank’s men to seize John as a potential hostage. Heading into the finale, all of the major characters are set on a bloody collision course with one another.

The series finale, “wow,” makes a point to suggest that redemption is still possible for these characters. No matter how bad things have gotten, these people still have the chance to make things right. It begins with something as simple as an admission. As Barry rushes towards its conclusion, the series suggests that the path to forgiveness and peace is found through the basic act of telling the truth. It’s difficult and it involves consequences, but these characters still have a choice to make.

During their standoff, Fuches offers Hank the opportunity to end their feud. “New deal: I walk away right now, you’ll never hear from me again,” Fuches offers. “All you have to do is admit that you killed Cristobal, admit that you fucked up. Admit that you were scared, that you hate yourself, that there are some days you don’t think you deserve to live. And the only thing that’ll make you forget is by being someone else.” He’s talking about Hank. He’s also talking about himself — and most of the cast.

Throughout “wow,” characters face that crucible. Confronted by Fuches, Hank breaks down crying and admits to his transgression. However, this moment of grace is fleeting. He shakes it off. “Go fuck yourself,” he instructs Fuches, leading to a bloody shootout. Hank bleeds out. He dies holding the hand of the statue of his lover Cristobal, unable to let go of the lie that he built around himself. Somehow, clutching to the lie is easier than admitting the truth.

Fuches gets a somewhat more optimistic ending. After all, it’s his epiphany that brings Hank right up to the line. Confronted with John, Fuches seems to feel some measure of empathy and compassion for Barry. Fuches knew Barry as a child and perhaps sees some of that innocence in John. He shields John during the shootout and walks the young boy through the bodies, covering his eyes to protect him from the horror. Fuches reunites John and Barry, before disappearing into the night.

Sally and Barry have a similar argument in the wake of the shootout. Lying in bed, Sally tells her husband, “You need to turn yourself in.” Barry responds that it wouldn’t be “what God wants for (him),” seizing on his good fortune as validation, “Honey, I’ve been redeemed.” Sally insists, “The only way to be redeemed is by taking responsibility for what you did. And the only way to do that is by turning yourself in.” Barry refuses. When he wakes up the next morning, Sally and John are gone.

Unable to find them, Barry journeys to confront Gene. Gene is currently under investigation for the murder of his lover, Janice Moss (Paula Newsome), a crime actually committed by Barry at the end of the first season. As such, the possibility of redemption presents itself. As Gene’s agent, Tom Posorro (Fred Melamed), tells Barry, “You’re the only one who can save him, Barry. This is an opportunity to do the right thing.” It is, perhaps, not too late. Things can still be made right.

In that moment, Barry seems to have the same epiphany that Fuches had when confronted with John. “You should call the cops,” Barry tells Tom. “I’m going to turn myself –” Barry is cut off mid-sentence. Gene shoots him, in revenge for his murder of Janice and everything else. In pulling the trigger, Gene condemns both of them. Barry dies, and any chance of exculpating Gene dies with him. It’s a bleak ending, a meditation on what happens when people can’t get past their grievances.

This is a tragedy, one rooted in these characters and their choices. It’s very important that many of these characters could have avoided their fates by making different choices — or by committing to their choices or even by making those choices before passing the point of no return. However, in its final act, “wow” offers a particularly cynical coda to this tale. The episode jumps forward another few years to catch up with Sally and John (now played by Hader’s IT co-star Jaeden Martell).

Warner Bros. has adapted Barry’s life into a feature film, The Mask Collector. The film stars Jim Cummings as Barry, presenting him as a victim of the sinister machinations of Gene, who is now inexplicably British and played by Michael Cumpsty. The Mask Collector smooths down any of the rough edges of Barry’s life story. It places a heavy emphasis on Barry’s military service as a signifier of virtue and purity, with Gene cast as a monstrous manipulator.

In the end, Barry is not in control of his own story. In that final act, “wow” shifts from the lies that people like Barry tell themselves to the lies that society itself tells about them. Barry has always been wary of the film industry as an empty fantasy world, critiquing everything from streaming service algorithms to the superhero industrial complex. It makes sense that Barry was drawn to Hollywood, precisely because it’s an industry built on fantasy and deception.

However, Barry makes a broader point about Hollywood and America. America is built on the myth of reinvention, the ever-expanding western frontier. “There was always a new start, over the mountains, over the plains,” wrote Thomas Merton. Merton argued American history “took place in the great unlimited garden where, in some mysterious way, it was not judged because it did not have any part in the ancient inscrutable intrigues of the old world.”

Of course, the western frontier has an endpoint. Manifest Destiny could only stretch as far as the unyielding Pacific. However, the entertainment industry took root at the limits of that expansion. “It is no accident that Hollywood was established in California, the coastal land of prosperity,” explains Priscilla Hobbs. “As the wilderness disappeared under the hand of civilization, it was replaced by the Dream Factory.” Hollywood could create an infinite, imaginary frontier built on that founding myth.

There is an ongoing effort in modern culture to reconcile the idea of American exceptionalism with injustices like the treatment of the indigenous population or the realities of slavery. In the final season, Barry ruminates on the legacy of Lincoln. He even frequently invokes religion, as if to argue that he is “called to a special destiny by God,” one of the core tenets of American exceptionalism. There are also ongoing debates about the monuments built to convenient historical myths, like Hank’s golden statue of Cristobal. Barry argues that the only way to get past these delusions is to admit the truth of what actually happened, not the comforting lie.

“Wow” argues that this choice may exist outside the hands of the individual. Watching a bootleg copy of The Mask Collector, John doesn’t get to hear the actual history lived by Barry or Gene. Instead, he consumes the reassuring lie told by Hollywood. It isn’t just people who lie to themselves; it’s society itself. In its closing moments, Barry tells a harsh truth.