There is arguably more great television than ever before. Already this year, audiences have enjoyed new shows like The Last of Us and returning shows like Yellowjackets. Although head of FX Networks content and production John Landgraf believes that peak television has finally arrived, and that the number of shows on the air will begin to decline dramatically, viewers still have a wealth of great programming at their fingertips. It’s difficult to imagine a better time to be a television viewer.

That said, the past year has felt like the end of an era. Many of the best shows of the past decade wrapped up. Last year, both Better Call Saul and Atlanta reached their conclusions. This week, Barry kicks off its final season. The last week of May will see the final episodes of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Succession, and Ted Lasso all landing on screens simultaneously. As different as those shows are, this feels like a big moment in pop culture.

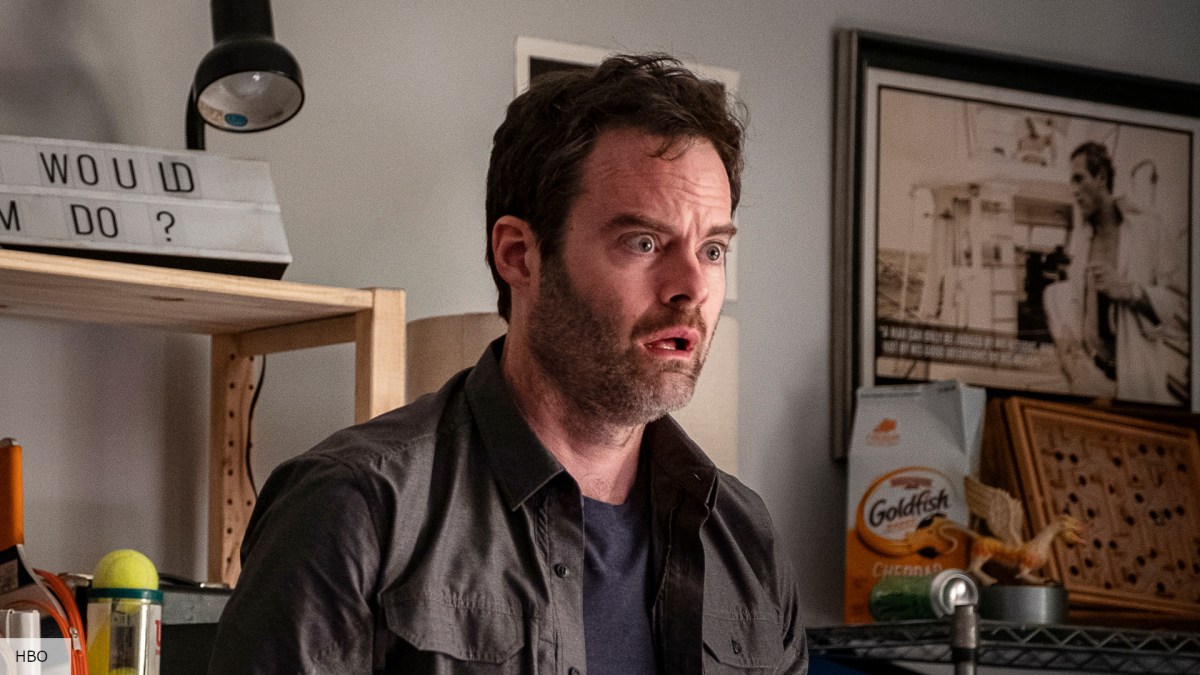

These are not traditional cancellations. These shows aren’t ending because networks have decided not to renew them. Jesse Armstrong has made it clear that the choice to end Succession was his own, explaining, “HBO has been generous and would probably have done more seasons, and they have been nice about saying, ‘It’s your decision.’” Bill Hader recalled the “anguished sigh” from the executive vice president of HBO comedy, Amy Gravitt, when he told her that he wanted to end Barry.

There is a lot to be said for allowing creators to end their stories on their own terms. This is how art has traditionally operated. A novelist writes their last sentence knowing that it is the end of the book. A playwright structures their play to build to its conclusion. A film director often chooses the final shot of their movie. There’s a reason many of the best endings linger in popular memory. The best of these endings feel like a line under a story being told.

Television has not traditionally operated like that, adhering to a separate set of constraints. Television is typically long-form, with individual episodes composing individual seasons, which add up to build the entire show. Historically, the shape of television storytelling has not been within the control of creators, but dictated by financial concerns. After all, even an episode’s runtime was historically determined by the advertising it had to accommodate.

For most of television’s history, the ending of a show was not determined by any artistic considerations, but by cynical business calculations. If ratings weren’t strong enough, shows could be pulled off the air. Between 2009 and 2019, it was estimated that 58.2% of broadcast shows were canceled in their first season. The trend continues into the streaming age, with services like Netflix becoming increasingly ruthless about canceling shows with multi-season arcs after a single season.

At least streaming shows get to finish their debut seasons. On broadcast television, shows could be canceled before completing a full season. There are plenty of shows (such as Profit or Firefly) that were pulled from the air so quickly that they didn’t get to broadcast all the episodes that had finished production. Some of those episodes eventually made it to DVD. It’s hard to imagine a satisfactory ending from a show not allowed to finish its first season.

Even for shows past their first season, the decision to renew or cancel can be made after production has wrapped on a season. Recently, it was announced that the fifth season of Star Trek: Discovery would mark the end of the show; production had already wrapped on the season. There were reports following the announcement that there would be “additional filming,” but it’s clear the season was not originally intended as an endpoint for the series.

Paradoxically, it has also been possible for shows to run too long. The traditional television model incentivizes networks to keep shows running past their prime. In a volatile market, sure bets are hard to find. From the perspective of a broadcaster, why would they allow any successful show to end while it was still drawing an audience? After all, the numbers clearly indicate that any replacement series is (at best) a coin toss. Why sacrifice what appears to be a sure thing on such a gamble?

It’s worth picking a specific example to demonstrate the way in which market forces can extend a successful series past the point where it can reach a satisfactory ending. The X-Files was one of the defining television shows of the 1990s. However, creator Chris Carter was always clear in his vision for the series. He imagined that The X-Files would run for five seasons and about one hundred episodes (a nice number for syndication), before transitioning into a feature film franchise.

Despite Carter’s assertion that “five years is a good length of time to do something” and actor David Duchovny’s stated desire to leave the show, Fox considered The X-Files too valuable to cancel. So the network renewed The X-Files for two more seasons, moving production from Vancouver to Los Angeles in order to make life easier for Duchovny. In press around the renewal, Duchovny stated, “I’d love to be off the TV show, but because of my greed I have to give them another two years.”

There are certainly things to recommend those two seasons, particularly the early stretch of the sixth season when The X-Files embraces an endearingly experimental outlook that fully capitalizes on its new California surroundings. However, the show undeniably entered a critical and commercial decline. Ratings slipped; reviews grew more acerbic. By the end of the show’s seventh season, it was clear that The X-Files had sharply declined from its creative and cultural peak just two years earlier.

Even in its diminished state, The X-Files was too valuable to cancel. As the show finished its seventh season, Fox was reeling from Fox’s “worst season ever.” Overseen by Doug Herzog, that season was described as “a train wreck” in contemporary press and saw channel viewership drop by 16%. The X-Files wasn’t the performer that it once was, but it was still needed. So, even with Duchovny embroiled in a lawsuit against Fox that was settled days before the finale aired, the show was renewed.

Given everything weighing against it, the eighth season was a minor miracle. It was stronger than the sixth or seventh and built to a satisfying conclusion that would have been a good place to leave the characters. Against all odds, The X-Files found its way back to an organic resolution. Unfortunately, this uptick in quality was reflected in the ratings, with the show increasing viewership from the tail end of the seventh season. As a result, the show was still too successful to be allowed to end.

Unfortunately, the ninth season of the show was a disaster. There were a variety of forces at play, including larger cultural shifts, but there were also more basic issues. Carter reportedly didn’t sign up until just before production began. Duchovny was completely absent, but his co-star Gillian Anderson was still under contract. By the end of its ninth season, The X-Files had gone from being one of the defining shows of the decade to a goofy punchline.

In hindsight, The X-Files remains fixated on its first five seasons rather than the ones that followed. In a retrospective interview, Carter noted that “everyone’s shooting for five seasons; everyone wants to do 100 episodes.” He has also confessed that he considered leaving after the fourth season, knowing that “the show was going to go on, and it would have gone on without [him].” When show writer Frank Spotnitz wrote an X-Files comic years later, he set it “between seasons 2 and 5 of the series.”

The X-Files is one of the more egregious examples of this trend, of a show that was kept alive well past its creative peak, whittling away its reputation through a narrative of inevitable decline. There’s a reason that the show’s seventh season fixates on zombie imagery in episodes like “The Sixth Extinction,” “Millennium,” or “Hollywood A.D.” So many classic television shows were kept on the air in a grotesque undead state, shuffling endlessly forward long after their vigor was lost.

However, any television viewer can point to sad examples of once-dominant television shows that allowed themselves to be gradually diminished through a series of cynical renewals. The Walking Dead wrapped up last year. At its peak, the show existed “in the rarefied company of TV’s most-watched shows,” competing with stalwarts like NCIS. However, those ratings plummeted sharply, and the series ended with more of a whimper than a bang.

There are any number of examples in recent memory, often buzzy genre shows that captured audiences’ attention and then continued to run to the point that many viewers simply forgot that they were on. Supernatural peaked in its ratings during the first season, with 5.82 million viewers watching “Route 666,” while the final season saw viewership drop below a million for the first time. How many viewers even remember that The Handmaid’s Tale is still running? Even The Mandalorian feels like it has finished its story, but it continues on.

Endings are important. The ending is the last part of a story that the audience experiences, and so they take that with them. Filmmakers have long understood the importance of a strong ending, not just to satisfy the audience but to protect the film itself. Endings are important in establishing “a key factor in that all-important marketing tool: word-of-mouth buzz.” How audiences talk about a film will shape its legacy and reputation and is often shaped itself by what they felt leaving the cinema.

It seems like critics and audiences have only truly begun to talk about television as an artform over the past two-and-a-half decades, whether fairly or not. However, any emerging artform needs artists. Recent decades have seen the embrace of showrunners like David Chase and David Milch as auteurs, the subjects of books like Brett Martin’s Difficult Men. These television creators must be allowed to tell stories rather than simply deliver content, and stories need endings.

It’s sad that shows like Better Call Saul, Atlanta, Barry, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Succession, and Ted Lasso are all ending within the same television season. It’s also sad that some of them have never been better. However, it also affords them a dignity of an ending on their own terms, something that other artforms take for granted, but which television has long been denied. To borrow a phrase from Succession’s petulant patriarch Logan Roy (Brian Cox), it’s important to know when to fuck off.