There’s an old curse, “May you live in interesting times.” This applies to blockbuster cinema in the 2010s decade.

It’s difficult to extrapolate clear trends over the course of 10 years, particularly in an industry as volatile and scattered as film production. There are always trend outliers and counter-examples, but it is possible to draw clear lines from one end of the decade to the other. This decade, that line is somewhat disheartening.

Much has been written about the state of major studio production in the 21st century: the crowding out of the marketplace with big-budget tentpoles that need to earn back their budgets in an opening weekend, the dependence on established intellectual property to sell these films, the way in which mid-budget films have gradually been squeezed out of the theatrical marketplace.

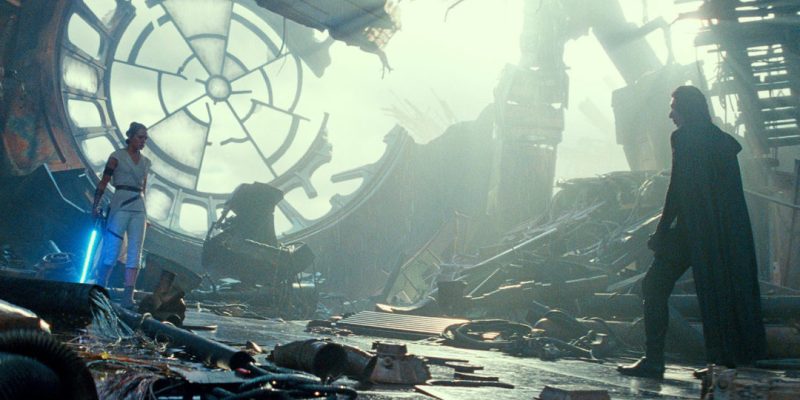

So much of the marketplace has been given over to blockbusters. Disney broke box office records in 2019 despite only releasing 12 movies — down from 23 in 2009. Almost every week of the year had at least one would-be blockbuster vying for the audience’s attention. Sometimes the season is so crowded that those films go head to head, as with Cats and The Rise of Skywalker.

With all of that in mind, it makes sense to consider the kind of blockbusters that are reaching the marketplace, the types of films that are receiving both budget and oxygen in the current cinematic ecosystem. More importantly, it is worth reflecting on how the production of those sorts of films has shifted over the past 10 years.

In the early part of the decade, studios invested in the idea of auteur-driven blockbusters. There was a belief that these films could be guided by a strong vision that could distinguish them from the competition and attract audiences to something novel and exciting. In some ways, this felt like a concession to the kind of mid-budget director-driven project that was becoming increasingly rare.

Christopher Nolan was the poster child for this approach. He reinvented the character of Batman with Batman Begins in 2005 and created a critical, commercial, and cultural smash with The Dark Knight in 2008. Nolan leveraged that success to make Inception in 2010 and was trusted enough by Warner Bros. that he could offer a definitive end to his take on Batman in The Dark Knight Rises.

The first half of the decade saw an increased level of trust invested in directors to bring their own stylistic sensibilities to established properties. Indie director Sam Mendes brought on a host of trusted collaborators to help give his own interpretation of James Bond to Skyfall in 2012, to rave reviews and commercial success.

Even the relatively conservative Marvel Studios embraced a more director-driven sensibility in the early part of the decade. Iron Man 3 was written and directed by Shane Black, who infused the film with his own distinctive sense of humor and playful irreverence. Guardians of the Galaxy afforded James Gunn the opportunity to present a more family-friendly slant with his own distinctive vision.

These films are not just among the very best blockbusters of the decade; they are some of the more interesting and engaging franchise films ever made. They offer an example of directors delivering satisfying studio product without completely erasing their own perspectives or insights. Iron Man 3 fits as easily with Kiss Kiss Bang Bang or The Long Kiss Goodnight as Iron Man or Iron Man 2.

At the same time, the early part of the decade reinforced the idea that properly marketed and scheduled big-budget releases from respected directors could become blockbusters. Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained and Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street were two unlikely Christmas-period blockbusters in 2012 and 2013, earning their directors’ highest box offices to date.

This trust in directors extended to a broader sense of ambition around these big-budget films even when they didn’t come from directors with an established authorial aesthetic. The rebooted Planet of the Apes trilogy from Rupert Wyatt and Matt Reeves stands among the most striking and confident franchises of the decade, in large part because it was willing to grapple with big ideas.

In the middle of the decade, a shift occurred. There were a number of high-profile controversies with directors attempting to impose their own distinctive visions on established properties. Despite his critical and commercial success directing The Avengers in 2012, Joss Whedon became embroiled in a bitter battle with Marvel Studios over the final cut of Age of Ultron. It was underwhelming.

In 2013, Zack Snyder offered his own take on Superman in Man of Steel. He followed it with Batman v Superman in 2016. The extreme response to two polarizing blockbusters led the studio to aggressively meddle in the production of Justice League, going so far as hiring Joss Whedon in an uncredited capacity. Even Whedon couldn’t get what he wanted from the studio. The results were disastrous.

Josh Trank seemed to implode during the production of a reboot of Fantastic Four, perhaps leading him to lose a gig directing a Boba Fett solo movie. Gareth Edwards directed Rogue One, only to have the final act heavily reshot by Tony Gilroy. Phil Lord and Christopher Miller were hired to direct Solo, only to get fired during post-production and have the majority of the movie reshot by Ron Howard.

At the same time, Marvel turned towards television directors. Patty Jenkins departed Thor: The Dark World to be replaced by Game of Thrones director Alan Taylor. He would later helm Terminator: Genisys. When the Russo Brothers directed Captain America: The Winter Soldier, they were best known for their work on Community. They ended up driving the shared universe.

There were many worrying press stories in the second half of the decade. Lucrecia Martel was told that if she agreed to direct Black Widow, she would not be directing the action sequences. Warner Bros. pushed back against the notion that they were in the business of director-driven blockbusters. Danny Boyle departed No Time to Die, arguably because his creative vision was too strong.

Of course, this may be alarmist. The second half of the decade included a few blockbusters with strong authorial vision. Wonder Woman is undoubtedly the work of Patty Jenkins. Rian Johnson crafted The Last Jedi as a delightfully idiosyncratic blockbuster, albeit one that broke the internet and perhaps even fandom. Still, these feel like exceptions where they were once the rule.

If these sorts of blockbusters are to become a rarity, that would be an immeasurable disappointment. After all, Mad Max: Fury Road has been a fixture of various end-of-decade polls, named as the best film of the 2010s by sites as diverse as Pajiba, World of Reel, and The A.V. Club. It is a triumph of blockbuster cinema, of a director given complete freedom and autonomy.

Although Fury Road is positioned almost perfectly in the middle of the decade, it is disheartening that a film like that seemed more likely at the beginning of the decade than it does at the end of it.