Keith Thomas’ Firestarter really wishes that it were a John Carpenter movie.

The film marks the second attempt to adapt Stephen King’s novel as a theatrical feature, following a largely forgotten 1984 adaptation from Mark Lester. The story has been updated for modern times; Charlie McGee (Ryan Kiera Armstrong) is told that students no longer need to dissect frogs, her father Andy (Zac Efron) calls himself a “life coach,” and farmer Irv Manders (John Beasley) watches Netflix documentaries. However, despite these tweaks, the film still feels rooted in the 1980s.

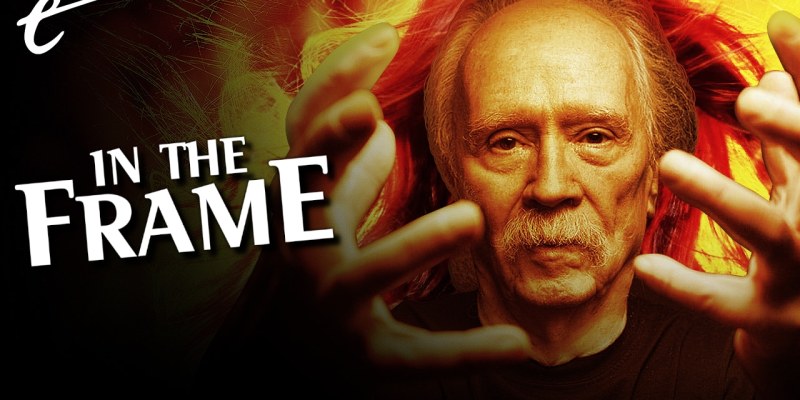

This throwback aesthetic is obvious in a number of ways. It casts classic ’80s movie heavy Kurtwood Smith in a small but pivotal role. However, it directly evokes a particular director. The movie features a score from John Carpenter, which Thomas describes as “his first score not directly tied to something that he had done.” Even the opening credits recall the old-fashioned openings to Carpenter’s movies like Escape from New York, The Thing, or Christine.

There is a wry in-joke here for horror film fans. Carpenter had originally been tapped to direct the 1984 adaptation of Firestarter, before Universal got cold feet following the critical and commercial disappointment of The Thing. Carpenter actually directed the underrated 1983 adaptation of King’s novel Christine, which Priscilla Page summarized as “Grease in hell.” When Thomas hired Carpenter to score Firestarter, he even directed him to mimic his soundtrack to Christine.

Of course, this isn’t just a sly reference to a mid-1980s horror cinema counterfactual. There is a reason why Thomas, working with Blumhouse and Universal, would choose to cite Carpenter as a reference for a film like this. It isn’t just that Carpenter has been re-evaluated in recent years as a genuine artist, to the point of receiving the Golden Coach Award at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival. Carpenter has become quite an industry for Universal and Blumhouse.

Blumhouse established a reputation off the back of the Paranormal Activity franchise, with its early success largely rooted in horror movies with budgets so low that they could not fail to turn a profit. However, the company entered the big leagues with two seismic Carpenter-inflected hits. In 2017, Jordan Peele’s Get Out, a social horror that the director acknowledged was indebted to Carpenter, earned $255M worldwide and scored four Oscar nominations including Best Picture.

The studio made a more overt homage to Carpenter the following year, with the release of David Gordon Green’s “requel” Halloween. The film’s budget is subject to some debate, but reports suggest it was the most expensive movie Blumhouse had produced to that point. The gambit paid off, with the movie earning $255M worldwide. It also gave the studio a viable high-profile franchise, spawning two sequels. Get Out and Halloween remain Blumhouse’s two most successful movies.

To be fair, Carpenter is at least profiting from the exploitation of his earlier work, and he is candid about how much he enjoys getting paid. “I’m mostly extremely excited, especially when they have to pay me money,” Carpenter remarked of the trend of remaking his movies. “I made my films and the remakes are the remakes, so (it’s) fine with me.” It is a mercenary attitude, but it is hard to object. Carpenter’s version of The Fog is a classic, but at least somebody benefits from the awful remake.

“If everybody else is making remakes and they want to pay me money to make a remake of an old movie of mine, why not?” he openly mused in interviews. By his own admission, he is “up for almost anything that involves money.” On the recent Halloween movies, he collects a double salary as executive producer and composer. Even Firestarter, which isn’t even directly adapting one of his films, is paying him for his work on the soundtrack. This is a much better deal than many comic book writers and artists get for billion-dollar adaptations of their work.

It is also worth conceding that Carpenter appears to be enjoying his retirement, particularly his status as a grand old man of American cinema. He is eager to share his opinions on Halo Infinite with the world. He found the time to make a guest appearance in, and provide the theme for, the Foo Fighters’ horror homage Studio 666, simply because the band had treated his son well while on tour 15 years earlier. Carpenter doesn’t owe anybody anything.

However, there is a sense that Carpenter deserves more. In particular, the veteran horror director deserves the creative opportunities that should derive from genre-redefining successes like Halloween, Escape from New York, or The Thing and beloved cult hits like Big Trouble in Little China or They Live. The problem is that Carpenter’s success has arrived on a very long timeline and that the film industry has an unfortunately short memory.

Carpenter never got to enjoy the fruits of his labor while he was doing the work. Many of his films opened to poor reviews and underwhelming box office, which were poison for a director’s career. Carpenter didn’t get to direct Firestarter back in 1984 because The Thing underperformed, but The Thing has since been reassessed as one of the greatest horror movies ever made. Getting to do the soundtrack to the Firestarter remake feels like a disappointing consolation prize.

There is something slightly frustrating in watching a generation of horror directors doing their best impersonations of Carpenter, capitalizing on the goodwill that these movies have slowly cultivated in the decades after they landed with a thud. These filmmakers are profiting from Carpenter’s work in a way that he never got to. If Blumhouse wanted to imagine what John Carpenter’s version of Firestarter might look like, why didn’t they simply give John Carpenter the opportunity to make it?

Carpenter wants to return to making movies, under the right conditions. “It would be a project that I like that’s budgeted correctly,” he explained at Cannes in May 2019. “Nowadays they make these young directors do (a) movie for $2 million when the movie is written for $10 million. So you have to squeeze it all in there and I don’t want to do that anymore.” He has insisted that “the conditions have to be right. There has to be enough money, and there has to be enough time.”

Carpenter has talked about how hard he had to fight to get his earlier movies made. He worked as composer on many of them because he “couldn’t afford anything else.” He has talked about having “to fight tooth and nail” with studios over the final cuts of his movies. In particular, Carpenter points to battles with “the head of a studio who was an intentionally cruel human being” over Big Trouble in Little China as something that pushed him away from studio filmmaking.

At the age of 74, maybe John Carpenter shouldn’t have to fight any longer. Perhaps the filmmaker who gave Hollywood movies like Halloween and The Thing should be trusted. Carpenter has certainly put enough in the bank that he should finally be able to make a withdrawal. It’s hard to believe that a studio like Blumhouse — which owes so much to Carpenter, both directly and indirectly — cannot justify giving the director a $10M budget, a loose schedule, and complete creative control.

Then again, maybe this is just a microcosm of a much larger issue that extends beyond horror cinema and beyond the specific debt owed to John Carpenter. After all, so much of modern blockbuster cinema ties back to nostalgia for intensely auteur-driven projects, with major studios often strip-mining those weird and personal success stories for spare parts. What do film studios owe to the artists responsible for creating the works that they exploit to stoke childhood memories?

Spider-Man: No Way Home coasts on nostalgia for Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy, to the point that actor Tom Holland even argued that director Jon Watts would emulate the “Raimi cam,” but (no matter what anyone says in interviews) Raimi seems unlikely to get to make his personal Spider-Man 4. The Flash will bring back Michael Keaton as Batman, building on nostalgia for Tim Burton’s movies, but no superhero film will ever get to be as weird or horny as Tim Burton’s Batman movies.

This is perhaps the fear that accounts for why studios are willing to mimic past successes of directors like Carpenter, but unwilling to invest in the talent themselves. There’s a real sense that Carpenter might not want to make a movie like Halloween or The Thing, even though the market wants more movies like Halloween and The Thing. What executive will make an argument for something that might pay off decades down the line, when they can cash in on an imitation of something audiences already like?

Still, watching Firestarter offer a pale and unconvincing imitation of the director that John Carpenter was nearly four decades ago, one wonders why a studio like Blumhouse isn’t interested in putting its money where its mouth is and perhaps rekindling one of the greatest genre directors of the past half-century.