Last week, Joe Russo offered a haunting vision of the future. The director, one half of the sibling duo responsible for Avengers: Infinity War and Avengers: Endgame, imagined a world where an individual might come home from work and direct an artificial intelligence to cook up a romantic comedy starring their avatar alongside that of Marilyn Monroe. In this hypothetical scenario, Russo proposed that such a setup could readily produce “a very competent story” for a potential viewer.

Russo was doing promotion for Citadel, the new show that he produced for Amazon Prime Video. Now that the first two episodes have premiered, Russo’s prophecy feels like a strangely appropriate way to sell the streaming giant’s lavish spy series. Citadel seems to have been crafted according to an algorithm that strives to reach “competent.” It’s not so much a show as a collection of familiar spy story clichés thrown together into a blender and then portioned out across an inoffensive six-episode season.

Citadel follows Mason Kane (Richard Madden) and Nadia Sinh (Priyanka Chopra Jonas), two operatives who work for the eponymous organization. After an expensive-looking opening set piece on a train in Italy, both Kane and Sinh are left suffering from “retrograde amnesia,” like the eponymous operative (Matt Damon) from the Bourne franchise. The show’s first action set piece is a bathroom fight, recalling Casino Royale. The show’s visual language employs the split screens of 24.

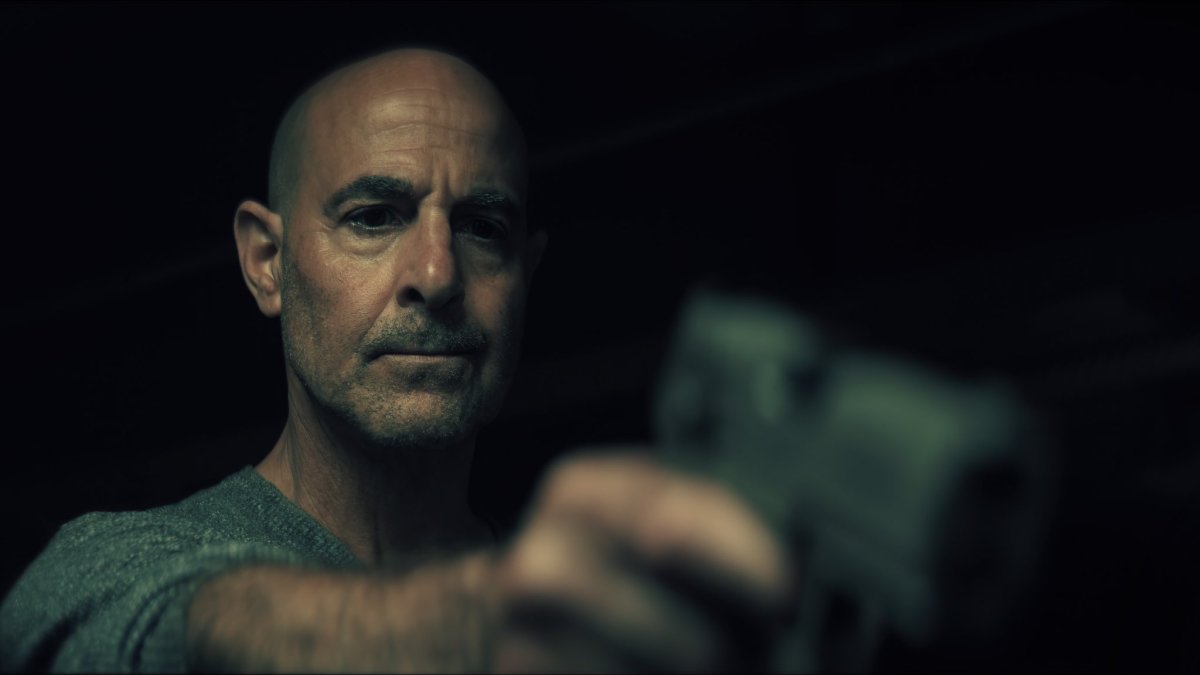

Citadel is a decidedly generic operation. As Bernard Orlick (Stanley Tucci) explains, Citadel is “a spy organization loyal to no man and to no nation. Loyal only to the safety and security of all people. You wouldn’t know we existed, but we helped shape every major event for good in the past 100 years.” Kane presses him, “We were the good guys?” Orlick replies, “The last line of defense for good in the world.” They are spies and they are good guys; that’s all there is to know. There are no specifics.

Even the show’s visual language feels ripped from other projects. The poster, a diagonal shot of gun-wielding Madden and Chopra Jonas with the title at 45° angle, recalls a one sheet for Christopher Nolan’s Tenet. While the series doesn’t really have a strong visual identity, its signature move is the 180° barrel roll, a shot favored by Nolan. As if the show had been designed by The Matrix itself, it opens on a barrel roll on Sinh walking through the train in an eye-catching red dress. As Ghosted director Dexter Fletcher recently noted, the opening has to grab the audience’s attention.

The plot itself is archetypal and broad. The first two episodes find Kane tasked with recovering “the Citadel X Case,” as generic a MacGuffin as possible, evoking both Alfred Hitchcock’s discussion of the utility of a generic plot to “to steal plans or documents, or discover a secret” and his specific example of “that package up there in the baggage rack” as a plot motivator. Of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with a generic MacGuffin, but the issue is that it’s indicative of Citadel as a whole.

To be clear, the problem isn’t that Citadel is particularly bad. It’s quite watchable. The show works reasonably well when it gives space to older performers like Stanley Tucci or Lesley Manville who can add a certain camp charm to the vacuity around them. However, Citadel is never particularly good, either. There is never a moment when the series feels alive or engaged. Then again, maybe this is the point. It doesn’t matter if Citadel is good or bad; it only matters that it is.

The show originated half a decade ago, from a conversation between Jennifer Salke, the head of Amazon Studios, and the Russo Brothers. Salke’s pitch was commercial, rather than creative. She wasn’t imagining an individual show, but an entire franchise. She proposed “an American-made show then eventually expand into multiple other series, set and produced in other countries and filmed in other languages, all connected within the same storytelling universe on Prime Video.”

There is something inherently hubristic in this, an executive willing an entire franchise into being without any concern for the particulars of an individual project. Hollywood learned nothing from the folly of the Dark Universe, Universal’s plan to build an elaborate interconnected set of monster movies from its classic intellectual property that never seemed to progress any further than a famously cursed image of the assembled ensemble, many of whom never even made a single film.

Despite only running six episodes, Citadel is reportedly the second most expensive television series ever made. Most estimates place its budget just behind that of another Amazon show, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power. There are rumors that it cost up to $300M. While this figure was driven in part by a chaotic production that involved extensive reshoots, Citadel is undeniably lavish. The show shot on location in countries as diverse as England, Spain, the United States, Morocco, and Slovenia.

As such, the show’s generic sheen is deeply frustrating. Citadel is ostensibly a globe-trotting espionage adventure like the James Bond or Mission: Impossible franchises, but it simply lacks their style and taste. Those movies often feel like travelogues, transporting theatrical audiences to beautiful and exotic locations that create a real sense of place: think Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) on top of the Burj Khalifa or James Bond (Roger Moore) visiting the Pyramids at Giza.

Citadel opens on a train, a spy movie staple. However, spy movies often take place on trains because trains are means of transportation to these exotic locations. The train sequence in From Russia with Love, for example, follows Bond’s (Sean Connery) adventures in Istanbul. The train sequence in Spectre brings Bond (Daniel Craig) to some lavish location shooting at Gara Medouar. In contrast, the train journey at the start of Citadel isn’t going anywhere. It’s a train journey for its own sake, because those happen in spy stories.

There’s a hollowness to Citadel, a show that aspires to rote competence. It’s a brand exercise, the foundation stone of a franchise that Amazon has already mapped out. Its existence is seemingly enough. It makes sense for the Russo Brothers to attach themselves to such a project. Citadel is ultimately just a more expensive cousin to The Gray Man, the $200M generic spy feature that the pair directed for Netflix and that the streaming service hopes to turn into “a major spy franchise” with sequels and spinoffs.

Given that the Russo Brothers directed both Infinity War and Endgame, two of the highest-grossing movies of all time and the culmination of over a decade of storytelling within the Marvel Cinematic Universe, it makes sense that services like Amazon and Netflix have come to think of them as visionaries who can conjure entire franchises into being. However, given the reviews for both The Gray Man and Citadel, perhaps it would be better to focus on making good movies and television and letting the rest take care of itself.

There is no small irony that Netflix recently launched its own lower-key spy show to much greater success. The Night Agent has much stronger reviews than Citadel and was reportedly Netflix’s most popular new show since Wednesday. Netflix has already renewed The Night Agent for a second season based on this performance. While there’s no information about the Netflix show’s budget, it looks considerably cheaper than Citadel. It’s an argument for ensuring the quality of the product, first and foremost.

Then again, Citadel has the weight of brand expectations pushing down on it. It’s not a show; it’s the foundation of a larger franchise. It’s even tied to Amazon’s interests outside the streaming service. The company has a helpful tie-in story that invites the audience to “shop Nadia’s look.” The synergy is so strong that critic Mark Harris noted, “I paused one minute into the first episode and got immediate onscreen prompts inviting me to buy the star’s red dress or ‘shop the store.’”

Of course, product placement has always been a thing. There is also a long history of vertical integration. Given that many American studios are owned by larger corporations, products and services provided by those corporations tend to work their way into the films produced by their subsidiaries; Sony has a long history of prominently showcasing its electronics in its blockbusters, for example. However, there’s something particularly unsettling about how direct these connections have become.

In some ways, Citadel is just indicative of larger cultural trends. It’s a rather blatant delivery mechanism for Amazon-branded content, whether that content is more shows on the streaming service or goods shipped from the storefront. It is no better or worse than what Disney does with its own intellectual property, with movies serving as trailers for streaming shows and providing content for lucrative theme parks and cruise divisions.

Streaming services like Amazon and Netflix just don’t have as deep a bench of existing brands as competitors like Disney or Warner Bros., so they have to actively will them into being. In the past, this happened organically, but nobody has time for that anymore. Citadel arrives as a prepackaged franchise. It’s just a shame there’s nothing in that packaging.