This article contains some spoilers for Cocaine Bear in its discussion of what cult film is and how the nature of sharing movies has changed.

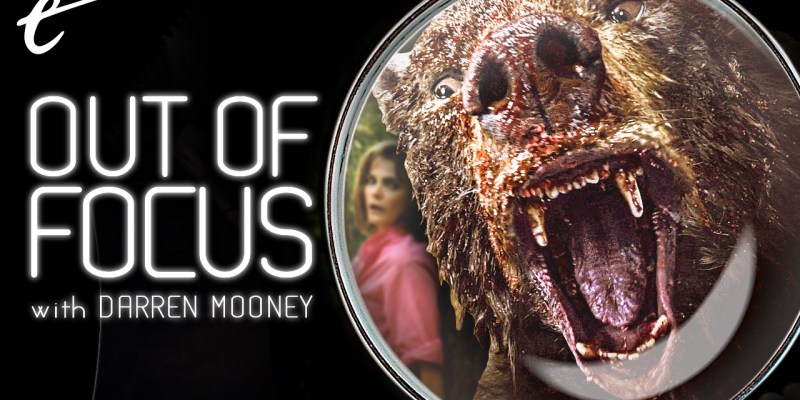

Cocaine Bear knows exactly what it is.

To be fair, the movie benefits from a very succinct and efficient title. It’s built around a (literal) high concept that actor Alden Ehrenreich has enough time to explain in the trailer. Twice. “The bear, it fucking did cocaine,” he explains almost directly to the camera. Then a few seconds later, in case the audience failed to pick up on the subtle nuances of that plot summary, he repeats, “A bear did cocaine.” For better and worse, that is all that the audience needs to know going into Cocaine Bear.

Reviews latched onto the idea of the movie as a pre-packaged cult film. K. Austin Collins opined that Cocaine Bear felt like “a cult-classic fetish object in the making since the release of its first trailer.” Clarisse Loughrey described it as “the kind of cult horror movie you’d find on a dusty VHS tape somewhere in a stoner’s basement.” Bilge Ebiri observed that director Elizabeth Banks and her team appeared to have “set out to make a cult movie on purpose.”

There are complications. As Donald Clarke pointed out, “you can’t manufacture a cult.” A cult film happens by accident and over time, rather than resulting from a predetermined process. This is a lesson Hollywood should have learned with Snakes on a Plane, a comparable attempt to create a cult creature feature that should also have served as a cautionary tale about the dangers of studios listening to loud shouty people on the internet.

That said, there is some value in Cocaine Bear’s efforts to chase the memory (if not the reality) of the classic cult film. After all, so many of the traditional paths to cult movie status no longer exist. Loughrey’s invocation of “a dusty VHS tape” is telling here. The explosion of cult movies was tied to the emergence of home video as a medium, in which there were physical objects that could be held and discovered — passed down and shared around.

There is a reason so many great directors to emerge during the 1990s worked in video stores, with Tom Roston’s oral history I Lost It at the Video Store serving as a spiritual successor to Pauline Kael’s film criticism classic I Lost It at the Movies. For fans of a certain generation, the availability of home media (and reserves of institutional knowledge from the staff working in the sector) made it easy to discover oddities and eccentricities.

VHS tapes were easy to circulate. They could be passed from elder siblings or classmates at school. Box art was often evocative, sometimes even better than the film. A catchy title, especially one written in a cool font, was alluring. At the same time, there was also something unique about it. A tape was often given or loaned. Whether renting from a store or borrowing from a friend, there was an expectation it would be watched — often promptly.

This explains the nostalgia for video stores, which even extends to the streaming services that have largely driven them out of business. There’s a grim irony to Netflix commissioning a sitcom called Blockbuster, set at a rental store, and then canceling it after a season. With the loss of the video store came a loss of curation. There are great curated streaming services like Criterion, MUBI, and even Shudder, but most are just bottomless pits of content.

Of course, there were other ways for movies to work their way up to cult status. Many film fans will recall the experience of flicking through the channels late at night, only to stumble across something strange and surreal that they would never have actively sought out. Again, that’s the power of curation, suggesting that there is something to be said for the old-fashioned linear television model as a way for an audience to discover things they’d never know to look for in the first place.

It is impossible to overstate the way in which both television and home media shaped public tastes. These afterlives were just as important to films as the initial theatrical release. It’s a Wonderful Life became a Christmas classic through television broadcasts. The Shawshank Redemption succeeded largely through its home media and television releases. The Princess Bride took “years” to go into profit. These are big movies. Imagine how important television and home media were to cult films.

To be fair, it is seemingly still possible for smaller movies to find audiences through streaming, although it seems much harder than it used to be. David Prior’s The Empty Man bombed in theaters before seeming to find an afterlife on streaming as a cult hit. Mark Mylod’s The Menu did not make a particularly big splash in cinemas, but it seems to have found an audience on HBO Max. Still, it’s easy to understand why Cocaine Bear would attempt to arrive with its cult status predetermined.

Cocaine Bear is certainly self-aware. The film includes a number of wry in-jokes that draw attention to its manufactured cult credentials. Set in 1985, the film goes out of its way to stage a reunion for three stars of the beloved prestige ‘80s-set television drama, The Americans, giving major roles to Keri Russell and Margo Martindale, while featuring Matthew Rhys in an early cameo. The movie’s villain is played by the late Ray Liotta, whose performance in Goodfellas made him an avatar of cocaine.

To its credit, Cocaine Bear had a good opening weekend. It earned $23M domestic and $28M global, an impressive haul for a film with a budget “in the $30M range.” It is another in the recent wave of genre films from Universal produced in the hopes of making a comparatively sizable return on a modest budget: M3GAN, Knock at the Cabin, Renfield. However, it also feels like Cocaine Bear’s theatrical release was just the first act.

For many modern movies, a theatrical release is a promotion for the film’s arrival on streaming. Encanto had a “subdued” and “disappointing” opening in late 2021, but it became the most streamed movie of 2022. Universal understands this. Despite an underwhelming performance in theaters, the video-on-demand release of The Northman was “a win” for the studio. Even this week, the streaming performance of M3GAN demonstrated that this logic was still in effect.

Cocaine Bear seems engineered for streaming success in a manner not too dissimilar from how those early cult movies organically found their audiences on tape or television. Most obviously, Cocaine Bear understands that its target demographic is technically prohibited from seeing it in theaters. The movie received an “R” rating from the MPAA in the United States, a 15 certificate from the British Board of Film Classification, and an 18 certificate from the Irish Film Classification Office.

However, Cocaine Bear is a movie that is very squarely aimed at teenagers who are too young to see it in cinemas. Banks leans into this. Cocaine Bear is technically an ensemble film populated by criminals and law enforcement officials, but the movie’s driving emotional narrative follows young kids Dee Dee (Brooklynn Prince) and Henry (Christian Convery), who skip school and end up crossing paths with the eponymous cocained caniform.

In form, Cocaine Bear is a kids’ adventure film. It is a gory and bloodier cousin of recent releases like The Adam Project, Stranger Things, or We Have a Ghost, affectionate throwbacks to the kid-centric pop culture of the era in which it is set. Banks understands that there is a certain transgressive appeal to this. There’s a scene where Dee Dee and Henry find a package of cocaine and try to take some. There’s a goofy subversion in adorable young Henry’s description of the bear: “It was fucked!”

However, it’s to the credit of Cocaine Bear that the film is internally consistent. It isn’t structured around transgression as an end unto itself. Childhood and parenting are surprisingly serious thematic concerns for this schlocky B-movie. Reflecting the anxieties of the era, both Sari (Keri Russell) and Eddie (Alden Ehrenreich) are single parents who are struggling both to get by and to protect their children from a seemingly hostile world. Eddie has his own issues with his father, Sid (Ray Liotta).

This theme of parenthood permeates Cocaine Bear. Two Scandinavian hikers (Kristofer Hivju and Hannah Hoekstra) are introduced discussing potential baby names. Bob (Isiah Whitlock, Jr.), a veteran detective, spends a lot of the movie navigating his complicated relationship with Rosette, an adorable dog that isn’t everything he hoped. Even the climax of the film reveals that the eponymous bear is a mother herself. Notably, she doesn’t kill Dee Dee but takes her back to her own cubs.

It may be too much to suggest that Cocaine Bear contains biting social commentary, but the film engages with the irony of the way that “the War on Drugs” offloaded responsibility from an older generation onto a younger demographic that had been largely left to fend for itself. Cocaine Bear replays Nancy Reagan’s famous “Just Say No” PSA, which made children responsible for preventing drug abuse, at the same time that the CIA was allegedly funneling cocaine into the United States.

As a story about two kids who are left to wander into the wilderness alone, menaced by a monstrous mammal, Cocaine Bear doesn’t feel too far removed from ‘80s coming-of-age classics like The Goonies or Stand by Me. Cocaine Bear just features more blood splatter and severed limbs, which makes it all the more enticing to younger teenage viewers. That target demographic might struggle to legally see it in theaters, but they’ll be waiting for it on streaming. They won’t “discover” it — they know it’s coming — but they will watch it.

Cocaine Bear is not an example of the sort of cult movie that it ostensibly aspires to be. It never could be. It lacks the organic surprise of an actual cult hit. Part of this comes from the movie’s intentionality and self-awareness, its attempts to manufacture something that can only happen organically. Part of this is rooted in the fact that the cult movies it is emulating simply do not (and cannot) exist today. As such, the deliberate invocation of that sort of filmmaking is as much an example of the film’s nostalgia as Sari’s bright pink jumpsuit.

Still, there is something very charming in all of this. Cocaine Bear plays as something of a hybrid, a film that evokes the thrill of a kind of schlocky B-movie that thrived in a secondary market that no longer exists while also understanding the logic of the emerging streaming economy. It also has a bear in it, a bear that did cocaine. What more could one ask for?