I’m not the first to remark upon the similarities between the just-released Conway: Disappearance at Dahlia View and Alfred Hitchcock’s classic thriller Rear Window. Indeed, the game invites the comparison in several ways, most overtly by sharing the premise of a protagonist confined to a wheelchair determined to solve a terrible crime by spying on his neighbors. Voyeurism is not the goal of these characters, but the very nature of their surveillance reduces the neighbors to objects of fascination. And in adopting the conventions of investigation games, Conway goes beyond voyeurism.

We tend not to think too hard about our invasions of privacy in games. RPGs often let us wander into people’s homes at any time of the day or night. Walking sims tend to invite us into lavishly designed environments that reflect their occupants. Other games like Life is Strange: True Colors or Dishonored 2 let us witness NPC secrets in more novel ways. In these cases, the freedom to intrude is a core function of the gameplay; we’re not supposed to question the morality of our actions. Conway: Disappearance at Dahlia View makes doing so unavoidable.

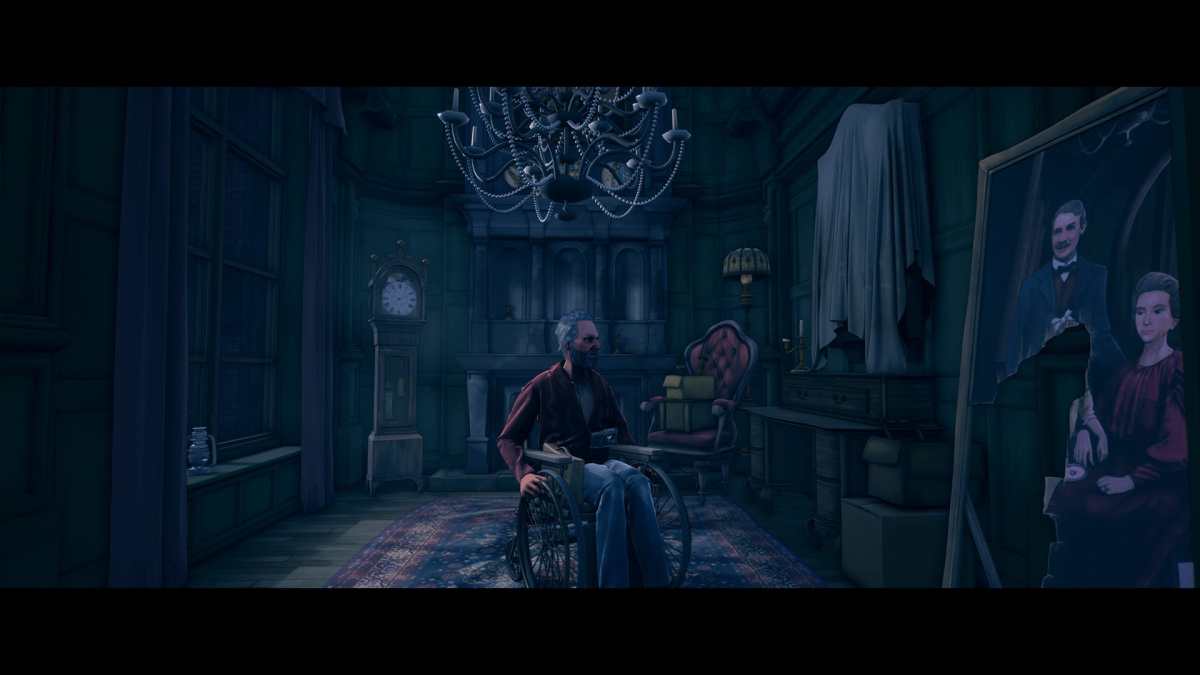

The game begins with Robert Conway waking in the middle of the night to a disturbance in the gated community of Dahlia View. One of the residents, Tony Morgan, has been attacked, and his eight-year-old daughter Charlotte May has been abducted. There’s a palpable sense of suspicion within the small community, with each resident raising concerns about at least one other. Despite a police presence, Robert takes it upon himself, as a now-retired private investigator, to crack the case.

The investigation is split into distinct sections, each canvassing a different neighbor and beginning with Robert’s surveillance. His observations are delivered from the window of his apartment as he gazes out at and takes photos of his neighbors. He remains in these moments the unobserved observer, tapping into the inherent pleasure of looking without being seen. In taking this as Robert’s starting point, the game reflects a defeminized view of Laura Mulvey’s assertion that the “determining… gaze projects its fantasy.”

Unlike Rear Window’s Jeff, who is fixated on the perpetrator, Robert is fixated on the victim. As such, everything he sees becomes a clue. Were Conway: Disappearance at Dahlia View a game like Umurangi Generation or New Pokémon Snap, that would be enough; Robert would give the police his opinions and let them deal with it. Instead, the game taps into another kind of pleasure, that of the armchair investigator, the sneaking suspicion that we might be able to solve a mystery if only we had a chance — as was so widely demonstrated following the real-life disappearance of Cleo Smith in Australia just last month. Robert unwittingly surrenders to these twinned pleasures and uses them to determine his reality: He can be a hero, if only his suspicions can be proven accurate.

This conviction gives him a sense of power that he uses to justify moving from observation to active investigation and interrogation. Likewise, Conway: Disappearance at Dahlia View shifts beyond voyeurism. Robert sets his camera aside and heads downstairs, visiting his neighbor’s apartments and questioning them. Nothing in this feels unfamiliar, except that Conway reflects the development team’s heritage of immersive sims more than most investigation games. Looking becomes touching, and the up-close-and-personal nature of the interactions makes that tangible. We enter into the homes and workplaces of the suspects, moving their belongings around, unlocking doors, examining objects in minute detail.

The voyeur’s gaze may be active and objectifying, but it ultimately remains passive in the sense that it always maintains distance. Conway turns the voyeur into something darker. The tactility adds dimension. The investigations feel invasive, especially with the knowledge that Robert is usually not welcome in his neighbors’ spaces.

The investigation process emphasizes the active role of the player, pushing the NPCs ever further into the role of object, of things to be examined rather than people to be considered. Ultimately, Robert’s fantasy blinds him to the possibility that his conclusions may be wrong, leading him to a further objectification, reducing his neighbors to the inanimate items he finds in their spaces — a curiously stained hammer, a cache of soporific chemicals, a damaged blunt object. Incriminating items, perhaps, but none the smoking gun Robert presumes.

And thanks to the participatory nature of gaming, we are complicit in all of this. The processes and conclusions are all on rails, which forces them to become our processes and our conclusions.

A common interpretation of Rear Window is that the film is a meta-commentary on the nature of the relationship between the cinematic screen and the audience. Jeff watches, as does the viewer, deriving pleasure through power of seeing what appears — thanks to the illusion of the cinematic apparatus — not meant to be seen.

If we regard Conway: Disappearance at Dahlia View as an homage and not-quite adaptation of Rear Window, the game must extend the metaphor. Robert enters the spaces that Jeff could only ever view. His entry to these spaces and his callous treatment of what he finds therein is scarcely short of violent. And if Rear Window highlights the illicit pleasure of watching, then Conway suggests a darker pleasure to be found in gaming — not just touching, but invading, controlling, defiling. It isn’t to make us question the morality of playing games, but rather the way we engage with games by following the rules they set out, rules that invite us to intrude into spaces that reality or society deems off-limits.

A grace is that Robert’s conclusions are often wrong; his actions are unjustified. Robert performs these actions in service of what he considers to be the greater good, just as we perform them in service of narrative or competition. If he can be wrong, mayhap that’s cause to pause and think about what we’re doing in the next game we play.