Gawking at the suffering of others is generally frowned on, unless they really, really deserve it. But in Days Gone, witnessing NPCs contend with the living dead does wonders for this zombie bike-em-up’s sprawling world.

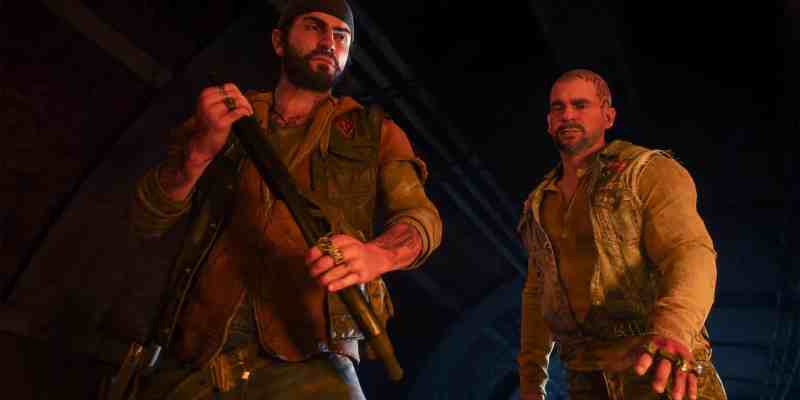

Sequel or no sequel (and the associated controversy is a whole other can of worms), there’s a lot to love about Days Gone. You get to play as Deacon “Christ on a Bike” St. John who, despite the game taking place during a zombie apocalypse, all but screams his “inner” monologue. Then there’s the sheer, ridiculous joy of firebombing a nest made of poo and twigs and hiding in a bin while the undead hunt high and low for the culprit. And outriding the dead only to turn a corner and find yourself face to face with a groaning, seething horde never gets old.

But what really elevates Days Gone is the aforementioned NPC behavior, which helps give the impression the world doesn’t revolve around you. MMORPGs aside, open-world games often resemble a video game version of The Truman Show; the world exists for your benefit and no one else’s. That may be the truth, but some games are better at hiding that fact than others.

Days Gone succeeds in this respect by introducing roaming non-player characters into its world who, for the most part, want nothing more than to survive. Sometimes you’ll see them wandering the world; other times you’ll turn up somewhere and they’ve beaten you to there. Sure, they’ll take a potshot at you if you get too close, but they’ve got more than enough problems of their own and, for them, you’re not the center of the universe.

The first time I ran into these roving NPCs, I’d parked up behind a tacky tourist lodge, ready to pick through the ruins for whatever crafting ingredients I could scavenge. Suddenly, through the broken window, I glimpsed some humanoid figures walking across the gas station forecourt. I whipped my binoculars out and — confirming they weren’t “Freakers,” Days Gone’s zombies — readied myself for a firefight.

A minute passed. Nothing. Another minute. Then a shot rang out, followed by an angry cry except, I quickly realized, they weren’t firing at me. They were shooting at the flesh-eating creatures that had caught sight of them. As I watched, they struggled to fend off the Freakers, succeeding at the cost of two of their number. I considered taking out the survivors, but reasoning that’d make me just as bad as the living dead, I rode off to let them mourn their departed.

You’ll run into multiple encounters in Days Gone, each entirely non-scripted, each with varying outcomes. It’s oddly heartening to see you’re not the only one getting into close scrapes; observing a horde, I watched a biker roar past, at which point half the horde broke off in pursuit. On rare occasions, however, you can witness something truly horrifying unfold. Seeing a small group fall prey to the undead is one thing, but I once saw a group of scavengers attract the attention of a whole horde, who fell on them like locusts.

But it’s not just the sheer spectacle of watching NPCs fight, of wondering who’ll come out on top in a humans vs. Freakers set-to – it humanizes them in a way that Days Gone’s core plot doesn’t. Watching each encounter unfold, I started wondering just who these people were, on occasion writing little mini-biographies in my head: How long had this woman known the rest of her group? What did she do before the fall of civilization? Was she on good terms with her fellow survivors? Or, having lost everyone she ever knew, had she cut herself off from all attachments? And having seen so many NPCs fighting to survive, I started asking myself one important question. How are they different from me? Aside from a heaping helping of plot armor, not an awful lot.

Are these encounters calculated to cast doubt on Deacon’s actions? Possibly. Days Gone does actively reward you for eliminating NPCs; anyone without a name is reduced to a handful of experience points. But intentional or not, it does reframe the wholesale murder you’re encouraged to participate in. It also made me notice the way Deacon’s quick to label the camps he stumbles across.

“Marauders! Those are the ones that have been making life hell for us!” he mutters, or words to that effect. Really, Deacon? Because the last time anyone ambushed us it was miles away from here. It’s as if, at heart, he knows he’s about to commit cold-blooded murder; he just needs to talk himself up to it. That, in turn, leaves things in your hands.

One key aspect of zombie fiction is that, once the dead walk and order crumbles, it’s people that drag things further down to hell. Walking into that camp, guns blazing, might net you a skill point or two, but to those NPCs, you’re the monster here. You’ve seen them or their fellow survivors fighting for their lives or narrowing eluding the dead. Are you really prepared to become the bogeyman just so you can level up quicker?

Days Gone’s roving NPCS may not have The Elder Scrolls: Oblivion’s Radiant AI, or names for that matter, but they bring the game to life in a different manner. Their struggles sell the illusion of a world where you’re not the only person struggling to remain amongst the living. In Days Gone, you’re only the most important thing in their lives if you choose to end them.