The week before last, writer C. Robert Cargill noted a curious pop cultural phenomenon. Acknowledging the 40th anniversary of the summer of 1982, one of the great blockbuster seasons, Cargill conceded that this summer is “a stark reminder of Gen X’s weird insistence that our movies and music aren’t old or classic.”

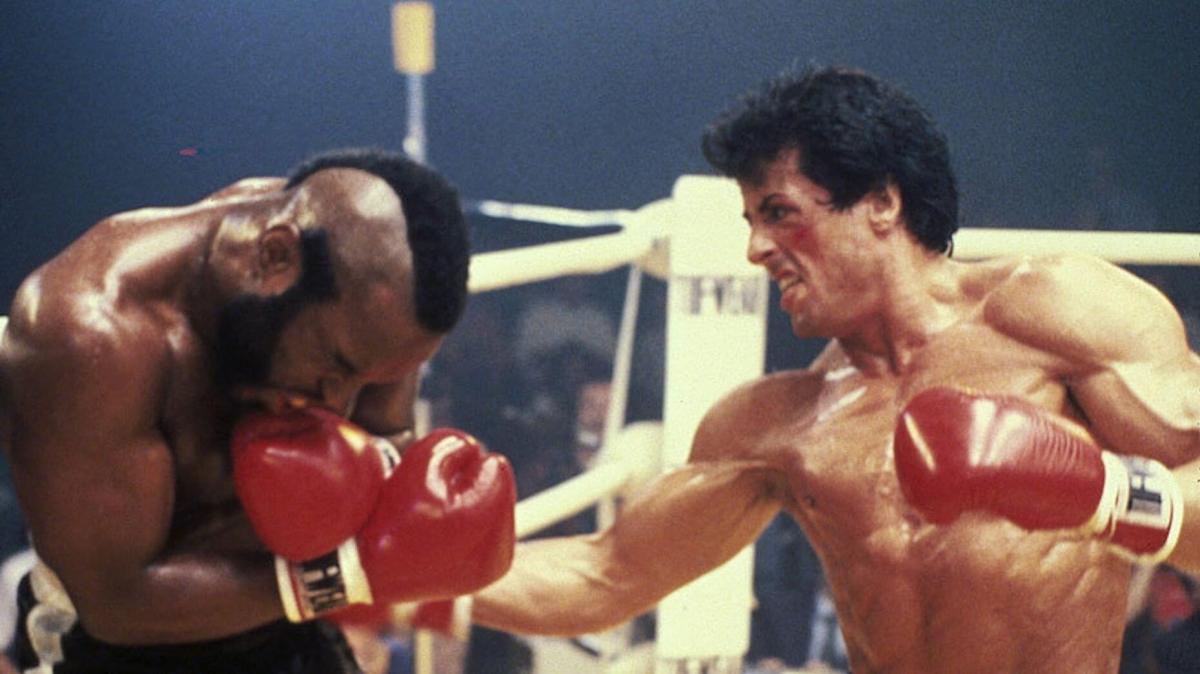

The summer of 1982 featured any number of classic movies in the U.S.: Conan the Barbarian, Rocky III, Poltergeist, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Blade Runner, The Thing, Tron, Mad Max II: The Road Warrior, The Beastmaster, An Officer and a Gentleman, and The Secret of NIMH. Even outside of the summer months, 1982 was a stacked year for movies, with late-in-year releases for movies like Halloween III: Season of the Witch, The Verdict, 48 Hrs., and The Dark Crystal.

However, most of those movies still feel oddly present. Few feel like “classics.” Cargill points out that watching something like Blade Runner or The Thing today should be equivalent to watching Casablanca, To Be or Not to Be, or The Magnificent Ambersons in 1982, but it doesn’t feel like it. The Godfather turns 50 years old this year, but it feels immeasurably closer to the present day than it does to something like Nosferatu made 50 years earlier.

There are likely several reasons for this. Most obviously, the gulf between black-and-white and color cinematography, along with the gap between silent films and talkies, likely makes the gap between something like An Officer and a Gentleman and Casablanca or The Godfather and Nosferatu seem bigger than it is. The film grain and the sound mix on something like The Verdict or Cabaret might betray its age, but they still look and sound enough like modern movies.

More than that, the emergence of home media during the 1970s and 1980s did a lot to ensure that the movies of the era were allowed to feel continuously “present” for younger audiences. Kids who loved Casablanca had to wait for a theatrical revival or maybe catch a radio adaptation. Kids who loved The Beastmaster could buy a video cassette copy and replay it continuously at their own leisure. Several of the classics of 1982, like The Thing, only became beloved in home media release.

There may also be cosmetic factors involved, particularly with more recent movies. Critics argue that American aesthetics have largely remained frozen in place since the 1990s. “The past is a foreign country, but the recent past—the 00s, the 90s, even a lot of the 80s—looks almost identical to the present,” Kurt Andersen noted in 2011. It remains true a decade later. Swap out the computers and cell phones and movies like Enemy of the State or Independence Day could be set today.

However, there is something else at play here. It was an emerging trend that was obvious even during 1982 but that would become even more obvious in the years that followed. Movies like Casablanca or Mrs. Miniver are largely allowed to stand as monuments to their time. They can become classics, snapshots of a given moment captured in celluloid. In contrast, the past half-century has seen Hollywood becoming increasingly reluctant to let any successful movie do that.

Looking at that list of great movies from 1982, many of them are already sequels: Rocky III, Star Trek II, Mad Max II, Halloween III. The year also saw the release of Amityville II: The Possession, Piranha II: The Spawning, Airplane II: The Sequel, and Friday the 13th Part III. Less than a decade earlier, Francis Ford Coppola had to be “seduced” to make a sequel to The Godfather, and Steven Spielberg dismissed a potential sequel to Jaws as “a cheap carny trick.”

There was a time when trying to franchise a successful film was seen as tawdry and vulgar. However, by the early 1980s, Hollywood understood it was just good business. Many of those blockbusters would spawn sequels and spin-offs. Some of them happened quickly. Conan the Barbarian would lead to Conan the Destroyer just two years later and eventually spawn a millennial reboot with long-simmering (or long Cimmerian) rumors that Schwarzenegger might return for a late sequel.

Even projects that bombed at the time would earn spin-offs in the decades that followed, with a prequel to The Thing in 2011 and a sequel to Blade Runner in 2017. Unsurprisingly, these attempts to franchise movies that failed to connect with audiences in 1982 also failed to connect with audiences decades later. Even movies from 1982 that don’t exactly cry out for follow-ups, such as An Officer and a Gentleman, reportedly have potential sequels in the works.

The only thing that could stop a successful movie from 1982 from spawning a franchise was a conscious choice. Steven Spielberg considered a sequel to E.T., even co-writing a treatment with Melissa Mathison, but decided against it. “Sequels can be very dangerous because they compromise your truth as an artist,” he explained. “I think a sequel to E.T. would do nothing but rob the original of its virginity. People only remember the latest episode, while the pilot tarnishes.”

To be fair, sequels were not an entirely new thing, even if Hollywood embraced them with renewed vigor in the late 1970s and 1980s. More than that, the industry did make a number of conscious efforts to franchise older classic movies. NBC tried to turn Casablanca into a television series in 1983. CBS broadcast Scarlett, a four-part miniseries sequel to Gone with the Wind, in 1994. However, these were exceptional cases, and when they failed to gain traction, Hollywood stopped.

Indeed, The Wizard of Oz might be the exception that proves the rule. Hollywood has been trying desperately to find a way to build a sustainable multimedia franchise out of the 1939 film for decades, moving in fits and starts. Disney tried to produce a loose sequel with Return to Oz in 1985. It also tried to produce a prequel with Oz the Great and Powerful in 2013. Neither proved strong enough to support a larger franchise. Universal is now adapting the musical Wicked in two parts.

There is a strange insistence to Hollywood’s desire to franchise, to the point that it seems to transcend even the logic of the market. These franchises perpetuate themselves against all reason. Despite the fact that Terminator Salvation was “a two-medium flop,” the franchise continued in Terminator: Genisys. When Genisys bombed, the franchise was placed “on hold indefinitely,” but Terminator: Dark Fate was released four years later. It also crashed at the box office.

This trend extends beyond films. Recent years have seen plenty of revivals of television shows from the 1980s through to the 2000s, often featuring the return of primary cast members: The X-Files, 24: Legacy, Fuller House, Heroes Reborn, Twin Peaks, Gilmore Girls, Star Trek: Picard, Wet Hot American Summer, Murphy Brown, Raven’s Home, Mad About You, Will & Grace, Dallas, and The Conners. There are no endings any longer; there is just the inevitable promise of more to come.

The result of all of this is that few pieces of pop culture are allowed to grow old and to become classic anymore. Instead, these characters and franchises are constantly dragged into the present. More than that, many of these movies often ask actors and characters to effectively restage or replay familiar iconography, making these sequels feel more like video game remakes than actual continuations or progressions of the source material.

There is a sense in which the recent Jurassic World movies are perhaps the perfect illustration of this reality, to the point that they serve as both a metaphor for the process and a cautionary tale about the dangers involved. The original Jurassic Park was a film about the arrogance of resurrecting something that died long ago, but the new Jurassic World movies often feel like they are trying to do to Jurassic Park what John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) was doing to dinosaurs.

There is an element of horror to all this. One of the most interesting aspects of the sorely underrated Scream 4 was the sense in which its villain, Jill Roberts (Emma Roberts), was essentially a Millennial stuck reliving the narrative of her Gen X aunt Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell). Jill tries to assert control of the narrative, to subvert it from the inside, only to discover that Sidney is unkillable, rising like Michael Myers in the hospital-set finale. Incidentally, Campbell is conducting public negotiations over her possible involvement in Scream 6.

This piece opened by referencing the summer of 1982, but the reality hews closer to one of the bestselling books of 1983, Stephen King’s Pet Sematary. Watching so many of these projects — from The Force Awakens to Ghostbusters: Afterlife to Jurassic World Dominion — it can feel like pop culture hasn’t just stagnated, but it has been unearthed and exhumed. Much like with those creatures buried at the eponymous graveyard in Pet Sematary, it can often feel like these beloved films came back wrong.

“The past is never dead,” argued William Faulker. “It’s not even past.” That seems particularly true of modern American popular culture, where the past is never allowed to remain in the past. It is never allowed to settle or take root but is always dragged into the present in the hopes that it can be harnessed and exploited. The result is a sort of dizzying pop cultural arrested development, a sense that the childhood wonder of 1982 has been stretched to sustain decades of blockbuster filmmaking.

It is perhaps wearing a little thin.