To paraphrase Zoolander, the multiverse is so hot right now.

The biggest movie of 2021 was Spider-Man: No Way Home, a story about three versions of the title character (Tom Holland, Andrew Garfield, Tobey Maguire) crossing over from three universes. One of the biggest movies of 2022 will be Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, in which the title character (Benedict Cumberbatch) is thrown across multiple universes. Two sequels to Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, Across the Spider-Verse and Beyond the Spider-Verse, are on the way.

However, the multiverse is not simply a preoccupation of contemporary superhero movies. Other genres in other mediums are also leaning into this thematic preoccupation. Streaming on Apple TV+, Shining Girls puts a novel twist on the classic serial killer narrative as it focuses on a survivor (Elisabeth Moss) whose reality seems to be constantly and dramatically shifting in the wake of her trauma. What was once a conceit of Star Trek and comic books is now a fixture of populist entertainment.

Everything Everywhere All at Once is proof of this. It is an indie film, shot on a meager budget of $25M. (For point of comparison, Robert Eggers’ gonzo blockbuster The Northman cost $90M while even Michael Bay’s relatively contained Ambulance cost $40M.) However, the film has become a genuine word-of-mouth sensation, grossing nearly $50M in a market increasingly hostile to low-budget films and even topping the box office just days before Multiverse of Madness came out.

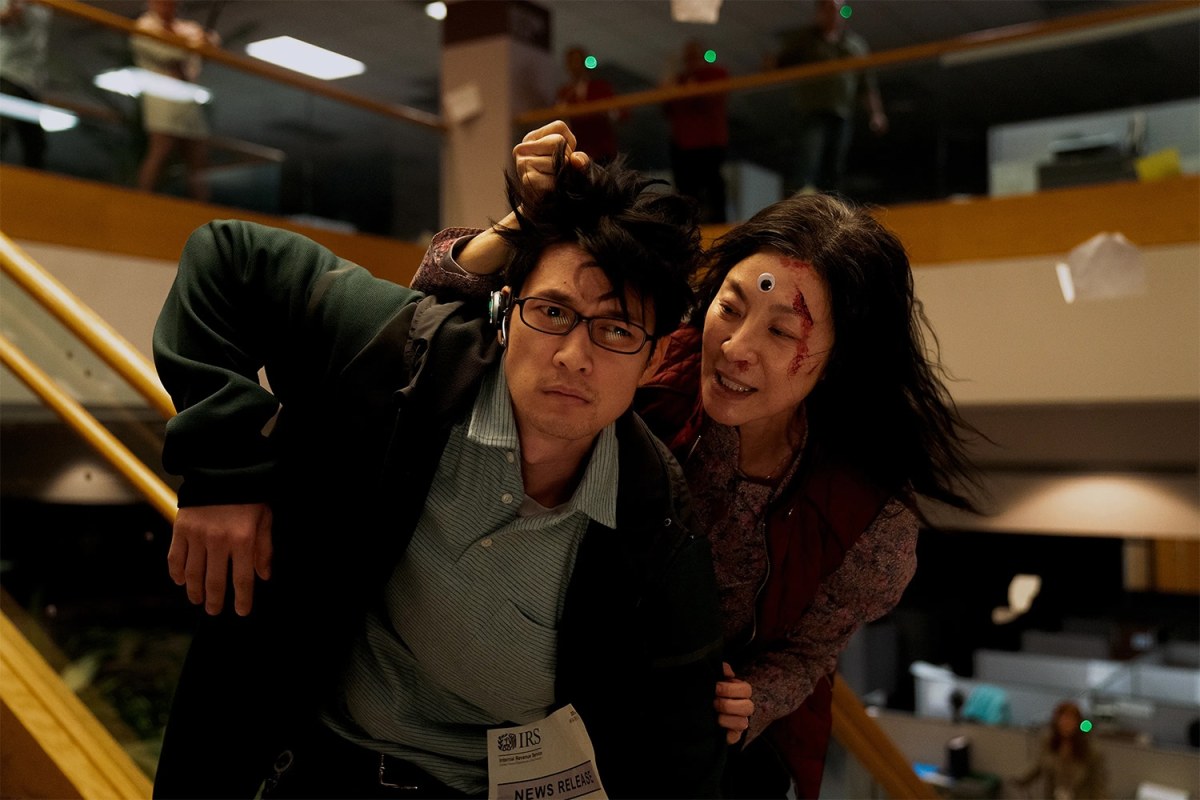

Everything Everywhere All at Once is a high-concept movie. It is part family drama, part martial arts movie, part absurdist comedy, part existential meditation. However, it is all built around the idea of the multiverse. It tells the story of Evelyn Wang (Michelle Yeoh), a Chinese immigrant who left her father (James Hong) to travel to America with her husband Waymond (Ke Huy Quan) and ended up managing a local laundromat that is being audited by the IRS.

Just as Evelyn finds herself contemplating all the choices that she made, she finds herself confronted by an alternate version of Waymond who warns her that a monstrous evil is spreading across the multiverse and that this failed version of Evelyn might be all that stands against complete destruction of everything everywhere. Evelyn’s response to this epic call to action sets the tone of the movie: “Very busy today. No time to help you.”

It would be reductive to argue that the success of Everything Everywhere All at Once is down to something as simple as the fact that “ticket buyers really love the concept of a multiverse,” even though some observers have tried to advance that argument to account for its over-performance. In our reality, it seems more likely that the film’s success — predicted on a sustained hold at the weekly box office — is rooted in the fact it is “an honest-to-goodness word-of-mouth sleeper hit sensation.”

Everything Everywhere All at Once is, to put it frankly, a miracle of filmmaking. It is in many ways a film that demonstrates the raw potential of cinema as a medium. It is the second theatrically released film from the creative team of Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, known collectively as “Daniels” or “the Daniels.” It is a joyride of a movie, shifting tone and style effortlessly. It is hilarious, heartbreaking, mesmerizing, ambitious, and assured. Audiences love it because it is just that good.

At the same time, it is interesting to contemplate why the multiverse has become such a strong recurring theme in contemporary pop culture. There are certain preoccupations that bubble through the various multiverse films, explaining why it might be a compelling hook for modern filmmakers even beyond the cynical opportunities that it presents for franchise brand management. There are aspects of the multiverse that resonate strongly in the current moment.

Interestingly, No Way Home, Multiverse of Madness, and Everything Everywhere All at Once are all immigration stories that use the multiverse to tie into that theme. No Way Home is a clumsy story about a bunch of inter-dimensional refugees that bungles any meaningful payoff. Multiverse of Madness is more consistent, particularly with the story of America Chavez (Xochitl Gomez), who finds herself separated from her parents and targeted because of her identity.

In Everything Everywhere All at Once, Evelyn finds herself wondering what might have happened if she never left home, confronted with an alternate life where she is a Hong Kong action star living out a version of Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love. The multiverse is a nice tool for this metaphor, which is understandably a big issue today. Not only does it render canon immigrants as literal immigrants, but leaving one’s home is one of the biggest “what if?” questions imaginable.

However, there is more to it than that. At a point in time when reality seems increasingly fractured, with significant segments of the population actively choosing to live in fantasy worlds with no connection to what is actually happening, the multiverse is an effective metaphor. It is a window that confronts characters with the lives they might have led and that tempts them with the siren song of infinite possibility. This is the most interesting aspect of Multiverse of Madness.

In Everything Everywhere All at Once, Evelyn finds herself tempted by the alternate life where she never left home, where she is rich and famous. She is drawn to it and actively seeks to escape into it, even though doing so threatens to destabilize the whole process. It is easier to live in an alternate world than it is to live in reality, particularly when reality can seem so depressing and even beyond repair. This is particularly true after a sustained period of global stress.

This more recent expression of this separation from reality is just an acceleration of trends that have been in motion for over a decade. The internet and social media have both overwhelmed users and provided them with the ability to rewrite their realities. Indeed, given that many of these multiverse projects were planned long before the pandemic and current political events, it seems more likely that they are extrapolated from those concerns about the internet’s warping effect on reality.

The Daniels have been quite candid that Everything Everywhere All at Once was inspired by their concerns about that fracturing of reality and the influx of information and media. “The internet had started to create these alternate universes,” explains Kwan. “I think this movie was us trying to grapple with that chaos.” It feels appropriate that the movie’s title mirrors comedian Bo Burnham’s description of the internet as “anything and everything all of the time.”

Everything Everywhere All at Once is about the idea of “too much,” the exhaustion that comes from being overwhelmed by an infinite array of possibilities. The movie’s antagonist is Jobu Tupaki, an alternate version of Evelyn’s daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu), who has experienced too many of the multiverse’s infinite possibilities and turned to a form of nihilism. Her father fears she is working on a weapon of mass destruction, a monstrosity created when she tried to put “everything on a bagel.”

However, Joy isn’t plotting to wipe out every reality. She has simply given up on her own existence. She plans to use the bagel in an act of self-negation. There is some grim logic to all of this. After all, Joy has seen everything and is still not happy. If everything is possible, then nothing matters. Evelyn finds herself wrestling with a similar nihilism as she makes her own journey through the multiple worlds. If she is just one of an infinite number of possible Evelyns, why does she matter?

At the heart of this high-concept story about multiple universes, the Daniels home in on some human anxieties: paralysis of choice when confronted with limitless possibilities and a sense of meaninglessness when confronted with a vast and overwhelming system. This is how the Daniels work. Their previous film, Swiss Army Man, was a movie about a farting corpse played by Daniel Radcliffe that was — like Everything Everywhere All at Once — a profound meditation on parenting.

Ultimately, both Evelyn and Joy find value in Waymond’s modest humanism, the idea that focusing on these big ideas and these massive struggles can blind people to the more modest happiness that they can find in connections to other people. Even before the movie begins, Evelyn is too wrapped up in her personal crises to connect with her husband. Evelyn and Joy don’t need an infinite number of universes; they just need to be present with each other and with Waymond.

It’s a simple idea, but it’s communicated beautifully. It is obvious even within the movie’s visual language. The bagel is a big recurring image in the movie’s first half: a thick black circle with a big white hole in the middle, a perpetual absence. However, that image can be reversed: a white void with a black circle at the center. These are the googly eyes that Waymond keeps at the laundromat and that Evelyn places as her third eye towards the movie’s climax.

This is the central premise of Everything Everywhere All at Once. Meaning is not something found in some abstract alternate world, but instead in being present in the moment. It is found in oneself and one’s connection to others. That is everything, everywhere and all — in one.