Halloween is fast approaching, so it seems like as good a time as any to talk about that most maligned of movie monsters: the Mummy.

The Mummy has been part of every major wave of Gothic monster movies. It followed Dracula and Frankenstein as the third of the major Universal Classic Monsters of the 1930s. It was the third of director Terence Fisher’s updates of classic movie monsters for Hammer Horror in the 1950s, behind The Curse of Frankenstein and Horror of Dracula. It arrived late to the party started by Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in the 1990s. It killed “the Dark Universe” in 2017.

The Mummy is interesting because it’s consistently the outlier in these cycles — sometimes for good, sometimes for ill, sometimes just for strangeness. The Mummy films always stand apart from the general tone of the monster movies around them, as if the production team has no real idea about what it is supposed to be doing with the core concept, and so adopt a “throw everything at the wall and see what sticks” approach that is curiously compelling.

By now, casual audiences understand the basic hook into each of the other classic monsters. Dracula represents threatening sexuality, what Stephen King called “the ultimate zipless fuck.” Frankenstein and his monster are about the horror of technology run amok and reproductive monstrosity. The Wolfman is about the animal trapped inside each human being, struggling to break free. The Invisible Man is about the fears of what a person might do if nobody else was watching.

So, what exactly does the Mummy represent? There are some big ideas tied to the monster. Notably, the original version of The Mummy was released in December 1932, just a month over a decade from the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb. Even into the 1930s, pop culture was fascinated with Ancient Egypt, particularly (largely apocryphal) stories about curses striking down those explorers who had violated the sanctity of these resting places.

The Mummy was just one piece of art reflecting this fascination with Egypt. The Art Deco aesthetic of the 1920s took cues from Egyptian culture. (Many 1920s movie houses would have been adorned with extravagant Egyptian décor.) Two years after The Mummy, Belgian cartoonist Hergé would publish the complete Cigars of the Pharaoh. That same year, Cecil B. DeMille would release his epic Cleopatra. This fascination might be seen as an extension of the “Egyptomania” of the late 19th century.

The Mummy is often read as an expression of “late imperial anxiety.” Like Dracula, the Mummy story is about a creature from a foreign land preying upon western protagonists. Unlike Dracula, the Mummy films are tied up in colonial exploitation; typically, an archaeologist has disturbed a sacred site of a foreign culture and provoked a monstrous response. Horror is built around transgression and punishment. In the Mummy films the transgression is intrusion into a foreign culture.

The films built around the Mummy have often struggled to articulate these core fears as clearly as those built around the other iconic monsters. Perhaps there are obvious reasons for this; the Mummy seems like a creature specifically aligned with particularly British postcolonial anxieties in the early- to mid-20th century than to any fears recognizable to a United States that was still emerging as a global power and still largely politically isolationist at the time.

This might explain why the Mummy often seems out of place in the context of the other 1930s classic movie monsters. Compared to Dracula or Frankenstein, rewatching The Mummy is a very strange experience. Most obviously, while the other films codified the appearance of their monsters for decades, the creature in The Mummy only briefly appears in its iconic wrapped-in-bandages form, which itself feels like a metaphor for the gulf between the perception and the reality of the monster.

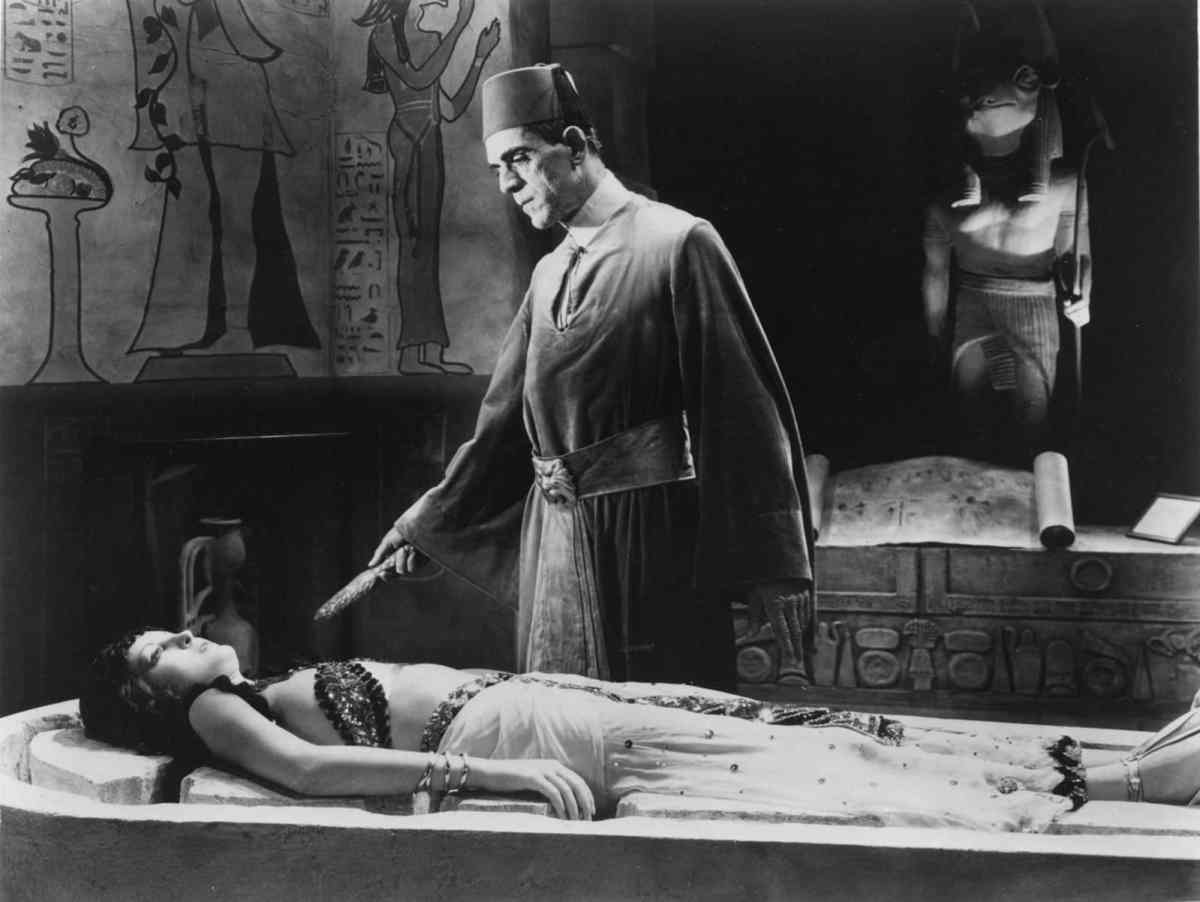

Instead, Karl Freund’s The Mummy feels like a retread of Tod Browning’s Dracula from the previous year, only starring Boris Karloff as the creepy foreign monster rather than Bela Lugosi. (Freund had worked as a cinematographer on Dracula and by some accounts co-directed it.) Universal had famously sold Dracula as a love story, and Lugosi became something of a sex symbol. However, there’s an appreciable difference in tone between Dracula and The Mummy.

A large part of this is down to the differences between Lugosi and Karloff as performers. Lugosi oozed raw and untamed sexuality, while Karloff suggested a more introspective tenderness and vulnerability. The Mummy is as much a weird timeless romance as a traditional horror. Under Freund’s direction, The Mummy leans more heavily into the aesthetic of German expressionism than Dracula or Frankenstein. The result is a movie that is somewhat undervalued by horror fans.

The Mummy was resurrected in the late 1950s as part of the Hammer Horror revival of Universal Classic Monsters. These films updated the monsters for ’50s audiences, with more violence and more explicit horror. However, there’s a sense of obligation to this adaptation, even reflected in the title. While Frankenstein and Dracula were boldly updated as The Curse of Frankenstein and Horror of Dracula, the British studio’s take on the shuffling Egyptian monster was simply titled The Mummy.

Terence Fisher’s 1959 adaptation is arguably more visually influential than the 1932 original, in that Christopher Lee spends far more of the movie lurching around in bandages. This take on the creature also taps explicitly into the colonial anxiety that powers the monster, which makes sense. Hammer Horror was a British production company, and it was making movies in the aftermath of the Second World War as the British Empire was being dismantled. That fear plays through.

The Mummy was clearly aimed at teenagers growing up amid the decline of the British Empire. The Mummy is focused on John Banning (Peter Cushing), the son of British explorer Stephen Banning (Felix Aylmer). The film is largely about John coming to terms with his father’s transgressions. It was Stephen who broke into the tomb and provoked the monster and who is committed to a “nursing home for the mentally disordered.” However, Hammer also struggled with The Mummy.

Like the earlier Universal film, it casts its lead against type. Peter Cushing was great as the creepy Victor von Frankenstein in The Curse of Frankenstein, the learned Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of the Baskervilles, and the wise Van Helsing in Horror of Dracula, but he doesn’t really work as a dynamic young lead. Similarly, the movie drags with extended flashbacks that kill momentum and seem to exist to stretch the runtime and get Christopher Lee out of makeup. Again, it’s an odd film.

The Mummy was next revived in the context of the more artisanal and auteur-driven monster movies that emerged in the 1990s. R-rated films like Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Mike Nichols’ Wolf, Paul Verhoeven’s Hollow Man, and even Stephen Frears’ Mary Reilly all consciously amped up the psychosexuality of their updates to classic movie monsters. Again, Stephen Sommers’ take on The Mummy stood apart from the crowd.

Sommers’ version of The Mummy was a PG-13 crowd-pleasing blockbuster with no aspirations beyond being a family-friendly pulpy throwback. The film is notable for its action set pieces and for the screwball comedy chemistry that exists between actors Brendan Fraser and Rachel Weisz. In this sense, the 1999 version of The Mummy is perhaps the only adaptation of the classic monster that has aged appreciably better than many of the self-serious monster movies around it, at least in the popular memory.

And then there is the most recent adaptation of The Mummy, directed by Alex Kurtzman and starring Tom Cruise. Although it arguably followed earlier updates like 2010’s The Wolfman and 2014’s Dracula Untold, Universal positioned The Mummy as the launching pad of a proposed “Dark Universe” that would fashion its monster properties into a cohesive shared universe. The movie failed so spectacularly that the universe was stillborn.

This failure allowed for a more intimate and contemporary approach to these established properties with Leigh Whannell’s reinvention of The Invisible Man. Even when The Mummy gets to go first and is pushed to the front of the lineup, it is still the odd monster out. There is something fascinating and compelling in this, even beyond the tacit understanding that most monster movie producers have no idea what to do with the concept.

Even almost 90 years after its theatrical debut, the Mummy is still a freak among freaks. There’s something almost heartening in that.