In recent years, the Final Fantasy franchise has become known as the RPG series that constantly reinvents itself. This is most obvious in Final Fantasy XV and XVI, the former of which is an action RPG and the latter of which might not be an RPG at all. The series feels even more ambitious when juxtaposed with its cousin at Square Enix, the Dragon Quest franchise, which nostalgically still uses some of the same sound effects that the original 1986 game blared out of mono-speaker CRT TVs. However, calling Final Fantasy a series that has always been committed to reinvention is an exaggeration at best and a myth at worst. The fact that Square Enix has bought into this myth could be giving the franchise a self-imposed identity crisis.

During the press tour for Final Fantasy XVI, producer Naoki Yoshida was asked more than once about what it is that defines a Final Fantasy game. On one occasion, he gave this answer: “a deep story, top-notch graphics, and moving music that ties it all together. Then you need a deep and complex battle system, and on top of that, you need a ton of content. And when you have all that – as long as you also have Moogles and Chocobos – all is well.”

Yoshida then went a step further and revealed what Final Fantasy series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi had told him when Yoshida asked Sakaguchi the same question: “(W)hat he said to me is that Final Fantasy is basically whatever the person making it at the time thinks is best for the series. There are no rules(;) you have the freedom to create what you want.”

Ostensibly, there is nothing wrong with any of those answers, especially Sakaguchi’s open-minded insight. It is how those answers have been applied to the franchise in recent times that causes some problems.

Related: Ranking Final Fantasy Games

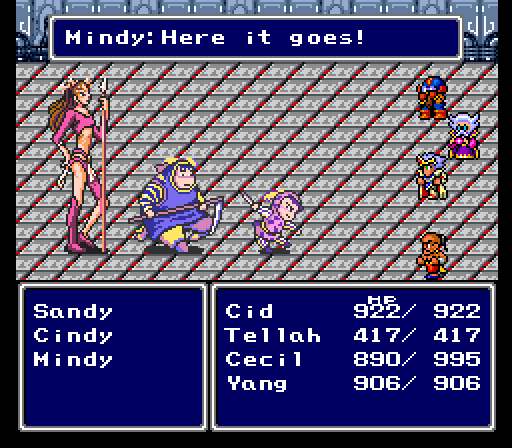

For starters, while Final Fantasy has always done its best to create striking visuals — it was brilliant to enlist Yoshitaka Amano to do illustrations for an NES game — “top-notch graphics” did not become a true concern until Final Fantasy VII in 1997. Rather, the first six games in the franchise were spit out on an almost annual basis beginning in 1987, with the graphics improving only marginally from one game to the next until Final Fantasy VI juiced things up a little. Final Fantasy IV on SNES / Super Famicom even reused some sprites from III on Famicom.

However, the point isn’t to nitpick. The point is to illustrate that Square had an Ubisoft mentality of “more games = more money” back then, and even Final Fantasy VIII through XI would release on an annual basis between 1999 and 2002. But the fans liked that. There was a familiarity and a continuity of visuals and audio from one game to the next. The menu design alone was enough for an enthusiast to recognize a Final Fantasy game.

Of course, things did change and evolve from one Final Fantasy game to the next, but describing that common iterative process as “reinvention” would be a step too far. For instance, every mainline entry had a brand new story in a new world, which was commendable, but until Final Fantasy VI, the games looked so similar that the new world and story didn’t really affect the game development timeline. In other words, creating a new world for those games didn’t cost much more than not creating a new world. It ultimately just made savvy business sense to give each game its own unique world, so any player could hop in without ever being beholden to existing lore.

And when Square became more ambitious with its visuals and it genuinely did cost much more to dream up the worlds of Final Fantasy VII and beyond, the games still maintained gameplay continuity. Final Fantasy IV through IX all used slight variations of the Active Time Battle system, meaning someone who played any SNES entry could comfortably work out any PlayStation 1 entry, with slight caveats. Even Final Fantasy X, which returned to a strictly turn-based battle system and featured a more linear world, retained enough visual continuity and similarities in its combat to be easily understood by series players.

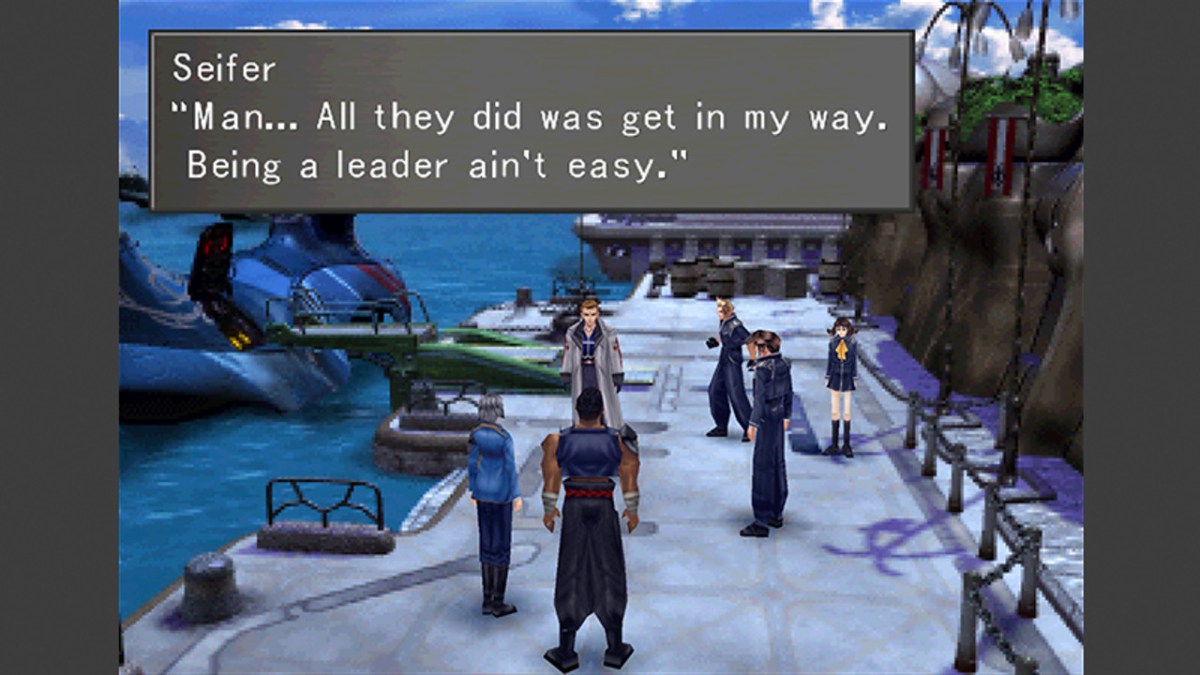

It’s striking that the two Final Fantasy games that genuinely did attempt reinvention during that period are the ones that have the most divisive reputation today. Final Fantasy II had a then-impressive narrative indebted to Star Wars (a recurring source of franchise inspiration), but its clunky battle system that removed experience altogether proved to be an evolutionary dead end (albeit revisited for SaGa). Final Fantasy VIII attempted to tell a love story using a plot device that felt too contrived even for fans used to contrived plot points, and many people despised its unusual battle system that often disincentivized fighting enemies at all.

Indeed, even Yoshida’s belief that Final Fantasy should have a “deep story” and a “deep and complex battle system” doesn’t hold water; you only really need one or the other. For instance, Final Fantasy V is arguably the most replayable game in the franchise with its outstanding “Job” system for battles, but its story feels lacking after what IV offered. Meanwhile, Final Fantasy VI and IX are two of the most beloved games by the hardcore fandom thanks to their outstanding narratives, but their battle systems are actually fairly simplistic compared to those of other franchise titles.

That brings us back to Sakaguchi’s belief — that Final Fantasy should have the freedom to become whatever its creators think it should be. It’s a refreshing position, and Square developers seem to have approached the franchise from this perspective since Sakaguchi left the company in 2003. The problem is that the mainline titles released since then have increasingly lacked the sense of continuity and familiarity that existed in the original 10 games.

Final Fantasy XII made the unusual decision to borrow parts of its world from Final Fantasy Tactics, and events played out across a semi-open world. While it certainly isn’t a bad game, its story and MMO-esque battle system proved as divisive as those of Final Fantasy VIII. Final Fantasy XIII then did a complete U-turn from XII, with its mutated take on Active Time Battle combat, a scoring system to go with that combat, and an extremely linear world that abruptly becomes open-world for the last third.

Related: Final Fantasy VII Rebirth’s Gold Saucer Is Going to Ruin Me

Final Fantasy XII and XIII are quirky games, to be sure, but they are still recognizably Final Fantasy. It’s really Final Fantasy XV, which began life as a Final Fantasy XIII action game spinoff, where the series identity started to become confused. Its story was infamously too unwieldy to fit in the game itself at launch, requiring DLC, a novel, a movie, an anime, and mobile games to finish. But more concerning than that, Final Fantasy XV feels like an imitation of Final Fantasy more than an actual Final Fantasy game.

There is a magic system because every Final Fantasy must have magic, but it is largely superfluous and forgettable. There is a world of ruin, just like in a beloved earlier franchise game. The soundtracks of old Final Fantasy games are available to play in the car that the heroes drive. There are even pixel-art representations of some of the characters. Decisions like these feel like a nostalgia play, an assurance to the fans that this is still Final Fantasy, but the results are mildly desperate and incestuous. Final Fantasy XV is not an open-world action RPG reinvention of the franchise. It is just a game with a long and troubled development cycle that happened to congeal into its current form before finally being kicked out the door.

Admittedly, Final Fantasy XVI feels much more like Sakaguchi’s expressed ideal. This game was developed with a palpable vision. It became an action game to convey the visceral story its developers wanted to tell, and frankly, the combat is quite good, if repetitive. Whether the story is actually satisfying is another matter, as it really leans on tired tropes later in the game. But that isn’t the biggest problem with Final Fantasy XVI.

The biggest problem with Final Fantasy XVI is that there will probably never be another mainline Final Fantasy game like Final Fantasy XVI.

Related: Final Fantasy XVI – Zero Punctuation

Final Fantasy is the franchise of reinvention now, according to Square Enix. It can be anything — even potentially a first-person shooter. Maybe XVI can get a direct sequel like X and XIII did, but it is the mainline, single-player, numbered games that define the franchise. And it is all but guaranteed that Final Fantasy XVII will look and play totally differently from XVI, just as XVI was completely different from XV, and XV was completely different from XIII.

That is a damaging thing because it means the familiarity in Final Fantasy is gone. The ability to iterate meaningfully and cultivate an identity for the overall Final Fantasy franchise is gone. Everything that grew beautifully or hideously among the first 10 (or even 13) games has been reduced to nostalgic iconography or discarded altogether. If Final Fantasy can be anything, then that means it is nothing but a hollow branding exercise. The presence of Chocobos and Moogles is irrelevant.

It’s no wonder that the Final Fantasy VII Remake trilogy exists. It’s a thing that people already know is supposed to be good because it’s using an excellent game as its skeleton. And ironically, it feels less like nostalgic pandering than Final Fantasy XV because Square Enix is using the trilogy to take Final Fantasy VII in noble new directions as an experience. Final Fantasy VII Remake isn’t a reinvention of Final Fantasy. It’s just a fun new take on something familiar, something that is distinctly Final Fantasy.

I hope that Final Fantasy can create a new familiarity for itself someday, but it won’t happen until it’s done trying to reinvent itself.