This coming week marks the fifth anniversary of Solo: A Star Wars Story.

The film was a commercial disappointment. It was also critically a step down from the previous three Star Wars movies: Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, and Star Wars: The Last Jedi. While both The Force Awakens and Rogue One had endured troubled productions, Solo was a notoriously difficult film to make. Lucasfilm had hired directors Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, only to part ways with them late in the production process. As a result, about 70% of the film had to be reshot by Ron Howard.

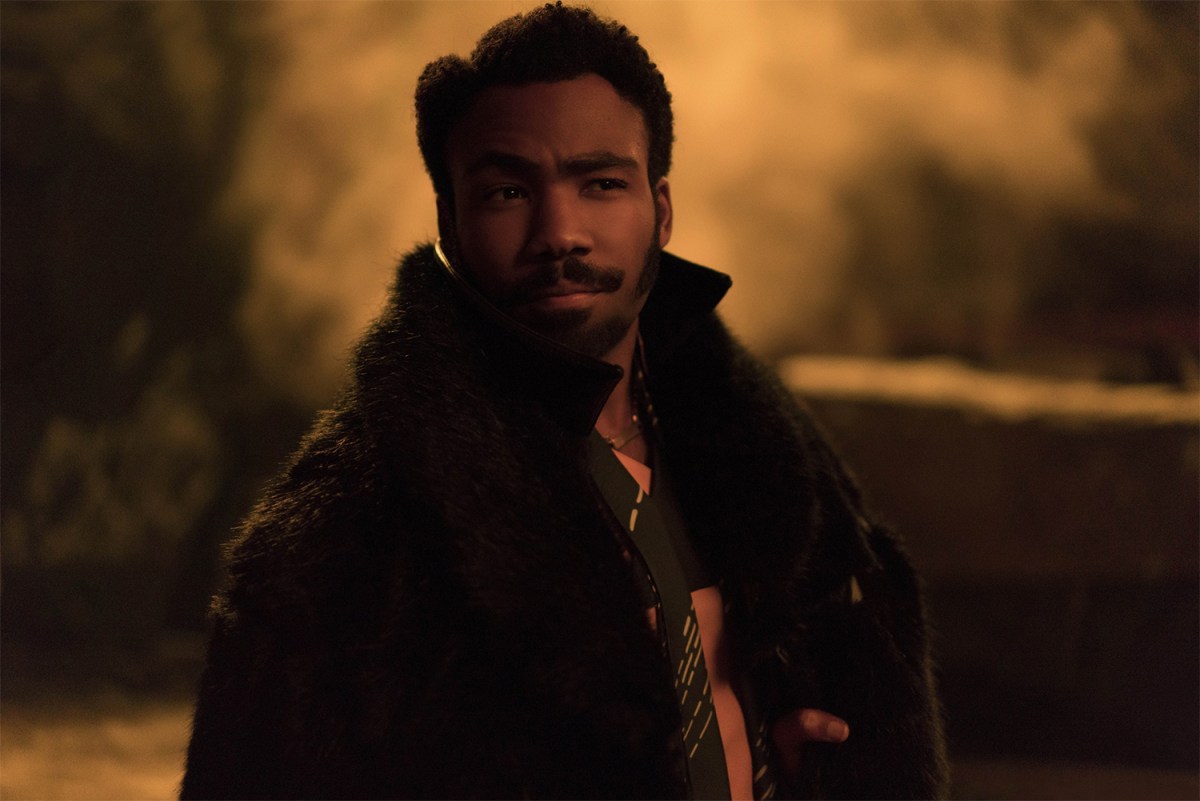

In some ways, Solo is a narrative dead end for the larger Star Wars franchise. It seems like actor Alden Ehrenreich will never be called upon to fulfill his three-film contract. Despite Kathleen Kennedy’s promise the “next” Star Wars priority would be a Lando Calrissian spinoff starring Donald Glover, it remains the subject of idle speculation. By Kennedy’s account, Solo’s failure was a “learning moment” that taught the studio what not to do. It made them wary of recasting these iconic roles.

That said, watching Solo with a little bit of distance, it feels like a strangely influential piece of franchise filmmaking. It is worth putting Solo in its context. 2017 had been an impressive year for the major franchises. After a somewhat rocky start with 2016’s Batman v Superman and Suicide Squad, 2017’s Wonder Woman had been a massive critical and commercial success for Warner Bros. Marvel Studios released both Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 and Thor: Ragnarok, two of its more distinctive films.

As much as nostalgia had come to dominate popular culture, 2017 saw ambitious filmmakers given the freedom to use established characters and concepts in interesting ways. James Mangold’s Logan placed Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine in a superheroic riff on Shane or Unforgiven. Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 offered a thoughtful and timely deconstruction of epic “chosen one” narratives. Rian Johnson’s Star Wars: The Last Jedi was the highest-grossing film of the year and one of its most timely.

Heading into 2018, there was a sense these established intellectual properties could serve as vehicles for filmmakers to construct resonant stories that spoke both to the deeper meanings of the source material and to the world outside of it. These weren’t just good franchise films; they were good films that happened to enrich their franchises. Of course, there were plenty of underwhelming and hollow blockbusters, like the remake of Beauty and the Beast, but there was also a lot of really good stuff.

Solo represents a speed bump in Hollywood’s approach to intellectual property. It’s a film that doesn’t just lack a strong creative viewpoint, but one that exists largely in opposition to the very idea of there being a strong creative viewpoint. The film doesn’t exist because Ron Howard has a particularly strong take on the character of Han Solo. It exists because Lucasfilm wanted a Han Solo film, one without the strong take offered by Lord and Miller.

Solo is obviously not the first Star Wars prequel. George Lucas released an entire trilogy of Star Wars prequels. However, Lucas’ disjointed and uneven triptych is compelling because it is much more interested in appealing to Lucas’ own idiosyncratic instincts than in accounting for the particulars of the original Star Wars trilogy. Lucas famously deleted a scene explaining how Force ghosts came to be, relegating that crucial plot point to a single throwaway exchange at the end of the last film.

In contrast, shorn of any strong directorial perspective, Solo instead preoccupies itself with the business of explanation. The film is constantly structured around references to things that the audience already recognizes, but it also goes out of its way to explain their significance. Solo is not so much a story as a collection of footnotes for a Wookieepedia article. It is a set of answers to questions that no sane viewer had ever thought to ask, because they weren’t actually important.

In its most maligned sequence, Solo explains how Han (Ehrenreich) received his distinctive last name. He has no family, and so an Imperial officer (Andrew Woodall) decides that he must be “Solo.” It’s a staggeringly pointless sequence, one compounded by the fact that Solo is no more or less absurd a surname than “Skywalker,” “Organa,” “Porkins,” or “Amidala.” None of those names ever required explanation. That this is a priority suggests the hollowness of Solo.

Solo runs through a checklist of trivia about Han Solo from the original Star Wars trilogy: how he won the Millennium Falcon, how he met Chewbacca (Joonas Suotamo), how he met Lando Calrissian (Glover), where those dice on the Millennium Falcon came from, why the Millennium Falcon has that gap in its front, and why it really made sense for Han to boast about making “the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs” in the original Star Wars.

While it receives less attention than the scene in which Han receives his surname, there is a particularly egregious scene that explains the origin of Han’s nickname for Chewbacca, “Chewie.” After their first encounter, Han asks for Chewbacca’s name. On hearing his partner’s full name, he replies, “Alright, well, you’re going to need a nickname, because I ain’t saying that every time.” Solo is a movie that feels the need to explain the concept of affectionate nicknames to its audience.

The result is a movie that feels incurious. There are new characters in Solo, like Han’s mentor Tobias Beckett (Woody Harrelson) or Lando’s droid L3-37 (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), but those seem unlikely to inspire their own spinoffs or to entice viewers to imagine their other adventures. Any future story about Qi’ra (Emilia Clarke) on screen will inevitably center on returning character Darth Maul (Ray Park, Sam Witwer).

In contrast, The Force Awakens had introduced a host of new characters, with Rey (Daisy Ridley) and Kylo Ren (Adam Driver) inspiring a passionate and enduring fandom. Rogue One introduced Cassian Andor (Diego Luna), a new character compelling enough to anchor his own self-titled spinoff series, Andor, which ranks among the best things that Star Wars has ever done. Even The Last Jedi introduced major new characters like Rose Tico (Kelly Marie Tran) or even DJ (Benicio del Toro).

A large part of the appeal of these major franchises, from Star Trek to Star Wars and from DC to Marvel, was the sheer size of the fictional universe. These worlds seemed to be infinitely complex. The cantina sequence in the original Star Wars is so important because it suggests that anybody in that bar could hypothetically be the star of their own movie quite apart from what is happening to Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) and Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness).

These franchises could support multiple entries because there was always more to see. Star Trek could be a show about a dynamic adventurer like James T. Kirk (William Shatner), but it could also be a show about an introspective diplomat like Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart) or a traumatized veteran like Benjamin Sisko (Avery Brooks). It could be a show in tune with the psychedelic 1960s or the unipolar 1990s and everything in-between. There were always strange new worlds to explore.

Solo made Star Wars seem smaller. This was true in terms of its release, coming just months after The Last Jedi. Up to this point, Star Wars movies had been events. With Solo, they just became generic blockbusters. However, it is also true in terms of the movie’s storytelling. There is a clear line to be drawn between Solo’s frantic desire to tie everything in Han’s life to a simple origin story and the grim inevitability of “somehow, Palpatine returned” in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker.

When working on Return of the Jedi, George Lucas argued with director Richard Marquand about the decision to give Luke a new lightsaber. Lucas flippantly observed, “I don’t know if we even need to explain it. The worst thing about that is you get a letter in Starlog magazine. Big deal.” These days, that letter is a $275 million feature film. While Solo flopped at the box office, its spirit endures. So many modern franchise installments are much closer to Solo than to Rogue One or The Last Jedi.

It’s true within the Star Wars canon. In its second season, The Mandalorian turned into a cavalcade of continuity references. Obi-Wan Kenobi built to a collection of payoffs involving cameos and memes. It also extends to other franchises like Star Trek. The finale of the first season of Strange New Worlds is an extended justification for the iconic visual of Christopher Pike (Sean Kenney) in a wheelchair from November 1966. The third season of Star Trek: Picard insists upon its own nostalgia.

Since their departure from Solo, Lord and Miller have explained that the central conflict with the studio was over the belief that Solo should be more than “just fan service.” They lost that battle. Five years later, pop culture is dominated by empty (and often strangely warped) nostalgia, reduced to a delivery mechanism for “fan service methadone.” So much modern franchise media is bereft of any perspective that it’s easier to point to exceptions like James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3.

Solo was a box office failure. However, like Palpatine, it wouldn’t stay dead. It was a sign of things to come, a blueprint for the franchise-heavy future.