This article contains spoilers for The Outer Wilds and Genesis Noir.

In recent years there’s been a growing number of TV shows, movies, and video games dedicated to exploring the meaning of life and death. The genius and popularity of NBC’s The Good Place seemingly kicked off a wave of deep dives on the subject like Disney Pixar’s Soul, and, on the games side of things, The Outer Wilds, Spiritfarer, and most recently Genesis Noir. Genesis Noir in particular is set before creation and tells a story encompassing the heat death of the universe.

All of these titles conceive an afterlife or a pre-life, where eons of time are spent by their characters trying to make sense of what happens on Earth. And while religion and philosophy have led the way on such heavy topics since the beginning of civilization, I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that games are carrying on the torch and doing the work to help the masses make sense of a chaotic existence.

In The Outer Wilds you play a character stuck in a time loop that lasts just under a half hour. Of course, you’re not aware that the day you head out on your first space voyage is the last day that will ever exist, and since everything resets with your memories intact, you assume it means you must find a way to save the solar system. It’s a natural conclusion for the player to draw as we’re often the center of the universe in a game’s world, but the ending doesn’t have you save everything; it instead has you break the loop after learning enough about a previous civilization’s arrival and eventual extinction in your solar system.

Once you learn the full story of their journey, you can feel content with the end of your own. The solar system was always going to burn out and die. There was never anything you could do to stop it; those attempts were futile. But in those final moments, as I sat around a campfire with other space explorers I’d met and learned from on the journey, I didn’t feel cheated out of a victory — I felt at ease.

In a direct way, The Outer Wilds made me cherish the time I spent exploring as what was important rather than the end itself, which was my obsession at the start. The overall meaning was not based around an event I had no control over and couldn’t stop.

The idea that it’s about “the journey, not the destination” is not new by any means; philosophers have dubbed this idea existentialism, which can be defined as “the nature of human existence as determined by the individual’s freely made choices.” The ability to choose what is and isn’t meaningful in your own life is what’s important, and this is why games are so uniquely capable of simulating a narrative with existential stakes.

Pixar’s Soul does a fantastic job of telling a story where the characters learn that their lives don’t have to be defined by a singular meaningful purpose. Instead they can find meaning in the gift of being alive in the first place — the simple things like standing in the sun, feeling the breeze, or spending time with loved ones. But as a movie, it’s a sort of secondhand self-actualization. You watch it happen to somebody else; it may inspire you, but it’s not your own.

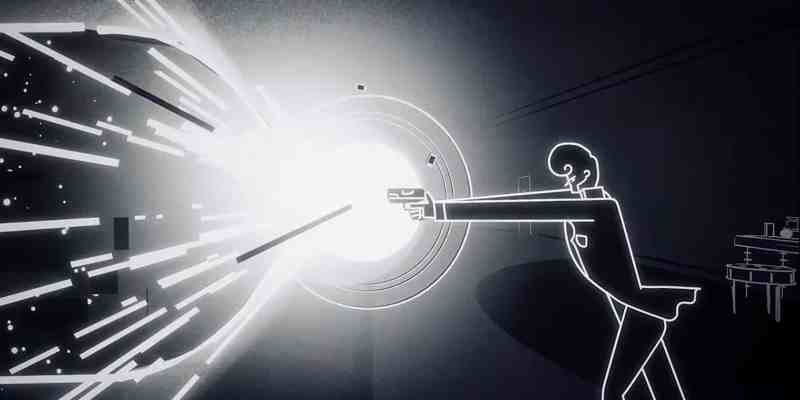

Genesis Noir puts you in the shoes of time itself represented by the main character of its game, No Man, who resembles a shady 1940s detective. No Man gets involved with a stunning lounge singer named Miss Mass, which spells the end of her relationship with the famous saxophone player Golden Boy. In a jealous rage Golden Boy fires a gun at Miss Mass, which in the game’s story is the actual Big Bang that marks the beginning of our known reality. In trying to save Miss Mass, No Man watches and studies the entire timeline of human history, from the primordial soup of single-celled organisms to a spacefaring humanity desperately trying to learn how to avoid the end of its own faltering star system.

The game’s interactions connect you directly with humanity by having you plant seeds of light that grow into flora and fauna. You create jazz music and experience how the random can be fun and exciting without following a given rhythm. You solve puzzles based on the Japanese art kintsugi where you repair broken pottery with gold or silver lining, highlighting the imperfect and giving it its own new value. You brood over solving a complex problem with a scientist and ultimately help advance humanity to their next stage.

In all these interactions in Genesis Noir, you as No Man start to fall in love with humanity and are given a choice of whether to stop the Big Bang to save Miss Mass and erase all of human history in the process. It isn’t a decision made easily. What Genesis Noir gives the player is an actual connection to that big moment of self-actualization. In an entirely different way, it arrives at the same profound conclusion that The Outer Wilds did.

In recent years the world has had a lot of death to mull over. Hundreds of lives lost to gun violence and police brutality, thousands lost to wars, millions to a global pandemic. Entertainment media and video games specifically can be powerful tools of escapism, ways to disconnect from the horrors of everyday life across a planet that’s dying faster by the day. Yet when done right, they can be one of the best possible methods of helping you cope with reality rather than escaping it. Genesis Noir in particular showed me that humanity is worthy of saving. Humans are capable of creating discourse that can calm a troubled mind and art that can fill a weary heart. After all, humans made Genesis Noir, and that game did those things for me.