There’s a curious lack of wonder and majesty to Warner Bros.’ “MonsterVerse” franchise.

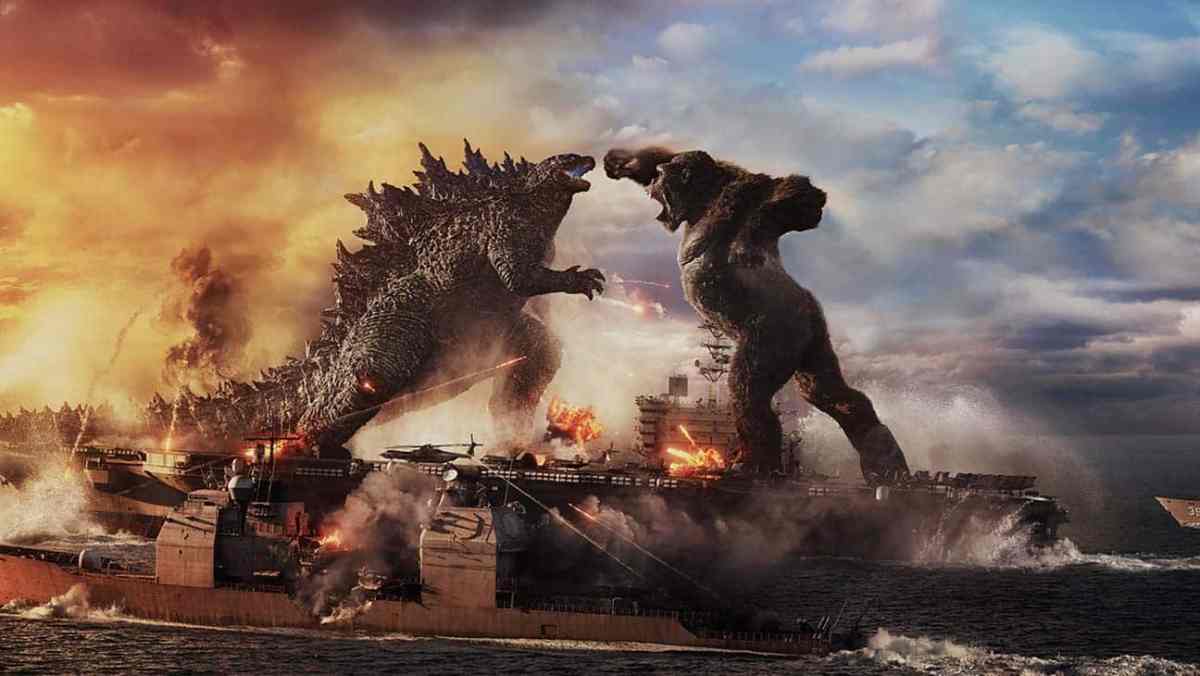

Godzilla vs. Kong certainly delivers on scale and spectacle, as the eponymous monsters level cities and demolish fleets. However, the action carries little weight. It never feels material or tangible. Instead, it plays as abstract. Unlike the very best monster movies, there’s never any real sense in Godzilla vs. Kong of what it feels like for humanity to suddenly find themselves in a world where everything that they thought they understood has been upended.

Some might argue that this weightlessness is just part of the transition from practical effects to computer-generated imagery, but that is not convincing. Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park was one of the first movies to digitally render its monsters, with four minutes of effects taking a full year to render, but even those comparatively primitive effects are still part of one of the most iconic and wondrous moments in cinematic history. No matter how many times one watches it, it’s magical.

Gareth Edwards drew heavily from Spielberg’s playbook when launching the MonsterVerse with Godzilla (2014). The structure of Godzilla is basically Spielbergian, focusing on the damaged relationship between Ford (Aaron Taylor Johnson) and his father Joe (Bryan Cranston), with the film becoming the story of Ford’s efforts to get home to his own family amid a global crisis. It’s not too far removed from how Spielberg approached his version of War of the Worlds just under a decade earlier.

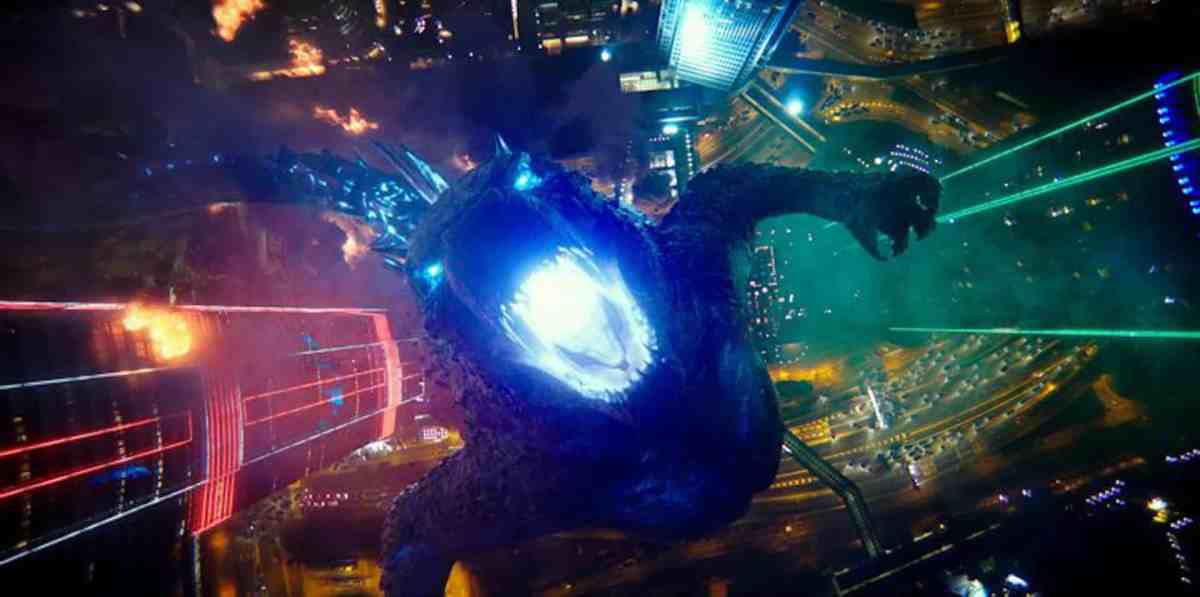

Edwards’ Godzilla probably comes closer than Michael Dougherty’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters or Adam Wingard’s Godzilla vs. Kong to creating that sense of majesty and awe. Repeatedly through the film, the action is glimpsed from ground level. The monsters are seen looming in the distance, the audience’s view obscured by closing shelter doors or glimpsed through shaking goggles. There is a tangible sense of the eponymous monster as something “too big” to take in its entirety.

Even the soundtrack to Godzilla is striking. One of the film’s most visually striking sequences — a HALO jump with red flares — is scored to the music of György Ligeti, the Hungarian-Austrian composer whose work was regularly featured in the films of Stanley Kubrick, especially 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Shining. Appropriately enough, it sounds quite similar to Krzysztof Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. The effect is haunting and nightmarish, making the creature monstrous.

Vivienne Graham (Sally Hawkins) describes the monster as “a god for all intents and purposes.” Godzilla is part of what might be called “the nouveau pop biblical epic” of the early 2010s, which included actual biblical epics like Exodus: Gods and Kings and Noah alongside blockbusters like Man of Steel and Prometheus. Like Godzilla, these were films that suggested that, if God existed, they were at best indifferent and at worst actively hostile to mankind’s continued existence.

In this sense, perhaps Edwards is one of the defining directors of the past decade. His three feature films — Monsters, Godzilla, and Rogue One — are all stories about human beings caught up in the catastrophic and apocalyptic events over which they hold little control. It is certainly, as the kids say, “a mood.” It feels poetic that Edwards arguably became one of his own protagonists during the production of Rogue One, with the film yanked away from him by forces outside of his control.

However, even allowing for Edwards’ sensibility, Godzilla tempers its awe and wonder with familiarity. Even before the first big action beat, the audience is introduced to Graham and Ishirō Serizawa (Ken Watanabe), essentially experts in Godzilla. When a freak accident at a mine in the Philippines uncovers a nest of monsters, Graham even asks, “Is it possible? Is it him?” Serizawa can confidently reassure her that it is not Godzilla. To Serizawa, Godzilla is knowable.

Over the course of the film, characters adapt to the existence of Godzilla and other monsters with surprising ease. Rear Admiral William Stenz (David Strathairn) handily identifies the other monster as a “M.U.T.O.: Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organism,” even though it is “no longer terrestrial; it is airborne.” Characters handily use the name “Godzilla” to refer to the giant monster, avoiding abstract nouns like “the creature” or “the incident.” It all seems very business-as-usual.

Of course, Godzilla is not business-as-usual. The monster is a representation of atomic era anxieties about mankind’s capacity for previously unimaginable destruction, with Godzilla directly alluding to the creature’s origin as a metaphor for the atomic bomb by having Serizawa carry around his father’s stopwatch that stopped ticking at Hiroshima. Edwards positions the creature as a metaphor for a more American tragedy, specifically 9/11 — most obviously in shots of firemen surveying the rubble.

The whole point of events like Hiroshima and 9/11 is that they fundamentally altered the way in which mankind viewed the world, with the two events even paralleled; there was no frame of reference for them. One of the strangest aspects of Edwards’ Godzilla is how quick it is to label everything that is happening, rather than to embrace the ambiguity and the horror of it. This trend only accelerates in the sequels, which increasingly treat this horror and spectacle as routine.

In Michael Dougherty’s King of the Monsters, the characters are confronted with numerous ideas that challenge any rational understanding of mankind’s place in the universe. There are dozens of other monsters. There is also a dominant self-regenerating monster named King Ghidorah, which is also an invasive species from another world. The planet is actually hollow. Washington D.C. is both flooding and burning simultaneous. Also, something resembling Atlantis exists.

That is a lot to process, even allowing for the events of Godzilla. However, none of the characters bat an eyelid at this, instead treating it as just another day at the office. At one point, Rick Stanton (Bradley Whitford) wanders into the room casually theorizing on how Godzilla can navigate the planet so quickly. “I’m telling you, Dr. Brooks was right,” Stanton states. “It’s a hollow Earth. That’s how he moves around so fast.” It’s like he’s discovered a new setting on the coffee machine.

If Edwards’ Godzilla is a very 2014 movie in the way that it recognizes the horror of an impossible force oblivious to the lives caught in its wake, then perhaps Dougherty’s King of the Monsters is a very 2019 movie in the way that it embraces the end of the world as something that people are just expected to roll with. There is perhaps something quite insightful in the numbness of these characters in the face of global extinction.

The problem is not that King of the Monsters embraces these big ideas; it’s that there’s never any chance for these ideas to breathe or to get a sense of how the characters react to them. What does any of this mean to any of the characters? What does any of this mean to the audience? What is the point of any of this? What are the stakes? What is the movie actually about, thematically or emotionally? The film is too busy delivering mythology and continuity — labelling and cataloging.

Characters in King of the Monsters bluntly state motivations and exposition. Mark Russell (Kyle Chandler) lost his son during the events of Godzilla and so doesn’t trust the monster. His ex-wife Emma (Vera Farmiga) is an environmental terrorist who plans to use the titans to reset the planet’s ecosphere. However, King of the Monsters never lets the characters sit with any of this, instead bouncing from one spectacular image to the next.

King of the Monsters’ trailer, composed of these genuinely striking images set to “Clair de lune,” might be the movie’s purest form. There’s more wonder in that trailer than there is in the finished film. Both King of the Monsters and Godzilla vs. Kong feature impressive human casts but fail to make any real use of them beyond exposition. Of course, the monsters are the prime attraction here, but good monster movies cannily use their talented human cast to better spotlight their creatures.

Human characters tell the audiences how they should react to what they are seeing. The most iconic moment in Godzilla isn’t anything involving the monster, but Serizawa saying, “Let them fight.” This is why reaction shots are important; an actor’s reaction to a shot can impact how an audience responds to the initial image. It’s an inversion of the classic Kuleshov effect. To bring it back to Jurassic Park, this is a trick Steven Spielberg has mastered, most obviously with “the Spielberg face.”

Characters in Godzilla vs. Kong don’t talk about the giant city-leveling monster as anything beyond human comprehension, but like an old family friend who has good and bad days. “Godzilla’s out there, and he’s hurting people, and we don’t know why,” Mark states early in the film. When Madison Russell (Millie Bobby Brown) sets out to figure out what has upset Godzilla, her friend Josh (Julian Dennison) asks, “Why do we have to help him?” Madison replies like she’s talking about a relative, “Because if we don’t, nobody else will.”

Godzilla vs. Kong has perhaps a single moment of wonder, but not one reserved for the human cast. In the middle of the film, Kong journeys to the center of the planet, to a strange realm where the laws of physics are suspended. Standing atop a mountain, Kong contemplates the weird gravity of this strange space, watching objects float, fly, and fall. There’s more wonder on Kong’s face in that sequence than in the rest of the film combined.

This is part of a larger issue with pop culture, as advances in special effects allow blockbuster climaxes to continually scale upwards. When audiences watch the earth face destruction in myriad ways week in and week out, it’s hard to be impressed by any of it anymore. More than that, as this sort of spectacle becomes commonplace, it becomes codified within the narratives. In the rebooted Mortal Kombat, Sub-Zero (Joe Taslim) isn’t a mystical paradigm shift, but simply a “superhuman.”

In the original King Kong, Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong) advertises the eponymous creature as “the Eighth Wonder of the World.” In modern iterations of these monster movies, the world could certainly use more wonder.