Hide and go seek is a classic kids game because it thrills everyone involved. Hide and you get the fun of trying to figure out the safest and sneakiest place to be, relishing when your friends walk right by you. Seek and you get to strike fear in your targets as you heedlessly stomp around leaving no door unopened. If you’re now too big, or at least too dignified, to wedge yourself under a kitchen sink just to prove you’re clever, you can still get some of that joy through hidden movement board games.

Pandasaurus Games’ Nyctophobia tries to embody the horror of slasher films, casting one player as a murderer and the other two to four as hapless genre archetypes trying to escape. The catch is that the potential victims all wear dark glasses so they can’t see the board, forcing them to find safety using just their wits and spatial memory.

Catherine Stippell’s blind uncle inspired her to make Nyctophobia since it’s a game he could play without any modifications. Only the hunter needs to see, setting up the board according to a set of prescribed maps in the rulebook. They then literally take players by the hand and guide them to their piece on the board. Players then feel around their piece to determine if they’re surrounded by trees or at the edge of the board before exploring more. The goal is to form a mental map of where you’ve been, communicating with other players in hopes of finding the piece representing the car — your ultimate survival goal — that’s parked somewhere on the grid. Every time you encounter the hunter you take a point of damage and you only have two health. When any player loses all their health, the hunter wins the game. That doesn’t really fit the horror genre, but it does prevent players from being stuck waiting around after they’ve been eliminated.

The hunted have a much harder time playing than the hunter. It’s hard to avoid accidentally cheating by feeling out more than the spaces you’re allowed to at any given time. Keeping mental track of where you’ve been is also hard, as my friend discovered after repeatedly running into the same forest walls. But avoiding the hunter is the most difficult part of the game. Whoever’s slasher has a full view of the board and a hand of cards they can play to make the players’ lives even more miserable. There are two antagonist types: the axe murderer, whose cards mostly let them chop through trees to make a beeline to their victims, and the mage who has the ability to move pieces around including rotating the entire board. The axe murderer is certainly a horror trope but I’m not sure how Stippel decided on a wizard for the other primary antagonist. The fact that players don’t really know what’s going on and can only feel that they’re not where they were or hear that things are moving makes that version particularly diabolical. Players do have their own abilities based on their roles — the cheerleader can give someone else an action while the forest guide gets to explore more of their surroundings — but none of them were strong enough to really stand up to the hunter’s options.

The rules encourage the hunter to play suboptimally by making moves that will give the players more time even when they could move in and attack. That’s something I absolutely hate to see in a game. I love running games like Pathfinder and Dungeons & Dragons where the goal is to challenge your players without killing their characters, but the enjoyment I take there is in building an encounter that’s tailored to that task. When the game is already built for me I feel like the balancing should be done well enough that I don’t need to hold back. Other one-vs- many hidden movement games like Fantasy Flight’s Letters from Whitechapel or Fury of Dracula have managed that balancing act so I feel like Nyctophobia should too. Pulling punches wasn’t fun for me and my friends were similarly discouraged when I told them I could have killed them if I wanted to. Eventually I stopped letting them wander around helplessly and closed in for the kill.

One weird side effect of the glasses is that the players have to be focused entirely on the game since you can’t easily grab snacks or check your phone between turns without risking seeing the board and ruining everything. The hunter is encouraged to mess with their blinded friends by making noises or even jostling them. I didn’t do that; my pets did it for me. One player said the highlight of the game for her was randomly being brushed up against by my cat and dog and trying to appropriately pet them without being able to see what she was reaching for. Not exactly a glowing endorsement of Nyctophobia’s gameplay, but entertaining nonetheless.

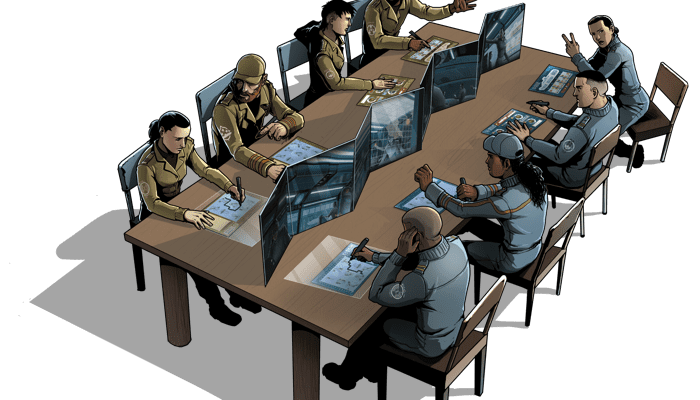

If you prefer more straightforward competition to making one friend the bad guy, you might want to try Asmodee’s Captain Sonar, which has two teams of players acting as both hunter and hunted as they pilot rival submarines. This is my friends’ go-to game any time we have eight people gathered because that’s usually too many to play anything but a party game. Each player takes on a role on the sub. The captain says what direction the sub will go in and is the one that gets to shout “Fire torpedos” when they think they’ve got their opponent in their crosshairs. The radio operator listens to what the other team is saying across the table and uses a map to try to figure out where the enemy sub is. The first mate is a go between for the other positions, making sure systems like sonar and weapons are ready when the captain needs them, which involves a lot of talking with the engineer.

Engineer is my favorite. It involves tracking the breakdowns that happen every time the sub moves and a lot of shouting, “I’m giving her all she’s got, Captain!” The sub can’t just rush off in one direction for too long or it will lose access to critical systems and eventually take damage. While it’s submerged, all the engineer can do is try to mitigate the damage done by advising course changes and prioritizing what systems to take offline. Repairs can be done on the surface, but that requires declaring exactly where you are on the map. While the opposing team starts beelining to your position and readying torpedoes, your team has to pass along an image of the sub and trace each section with a dry-erase marker as fast as possible. You then pass your work to the other team, who judges whether your tracing was neat enough for the repairs to be considered successful. The fact that they’ll need to eventually do their own repairs keeps teams from being jerks, but there have been times where it was obvious we needed to take a second agonizing pass. Also sometimes one team reacts to the other sub surfacing with pure relief since both groups get a breather to make repairs before resuming their hunt.

The whole thing is chaotic and delightful. The shouting is only broken up by periods where one sub activates their stealth drive, letting them move four spaces without any indication where they’re going, communicating with your team using hand signals hidden by the divider that sits between the two groups. Things are only further complicated by specific rules for each scenario which are meant to add replayability value. It’s hardly needed because it’s so hard to wrangle eight people together that it always feels fun and novel when we actually get to play.

Most competitive games have an aspect of hidden information, whether it’s what cards you’re holding or some secret objective you need to complete. But making the very location of your opponent unknown provides a different kind of excitement. These two games will deliver the thrill of the hunt and the fear of the hunted, no crouching required.