This year, Hollywood is in something of a decadent phase.

It’s obvious in a number of different ways. This year’s end-of-year releases tend towards bladder-testing runtimes: Blonde is 166 minutes, Tár is 158 minutes, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever is 161 minutes, Babylon is 189 minutes, Avatar: The Way of Water is 192 minutes. While claims that movies are getting longer tend to be exaggerations unsupported by the data, this year’s end-of-year releases do feel like they are luxuriating in themselves.

This indulgence is obvious in other ways. Following the success of Roma, there has been a huge business in auteur directors producing semi-autobiographical accounts of their own childhood, often celebrating their love of film as a medium. This year, however, has seen the semi-auteur-biographical picture become a mini-genre unto itself: Richard Linklater’s Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood, Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans, James Gray’s Armageddon Time, Sam Mendes’ Empire of Light.

The film industry is in a state of flux, and that instability informs a lot of recent high-profile releases. Andrew Dominik’s Blonde was a deconstruction of one of the great myths of Hollywood’s Golden Age, but it also felt like the apotheosis of a certain kind of indulgent streaming blockbuster. Damien Chazelle’s Babylon is a story about the end of the “wild west” silent era in Hollywood, but its apocalyptic vibes certainly resonate in similarly uncertain times for the medium.

There’s an obvious nostalgia in all this, in filmmakers mythologizing themselves and mythologizing Hollywood. However, as tends to be the case, that nostalgia is rooted in a fear of what the future might hold and that this might be the end of something. Top Gun: Maverick was a runaway success and a celebration of Tom Cruise’s movie star power, but it was also a movie built around accepting the reality that actors like Miles Teller and Glen Powell are never going to be able to replace Cruise.

It is a weird vibe, at once celebratory and mournful. It’s a wild party in which Hollywood is celebrating itself, as it is wont to do. However, everybody at that party is aware that the sun is coming up and that there’s going to be a huge mess to clean up. Warner Bros. could reportedly only afford to release two movies in the final stretch of the year. James Camron has admitted that The Way of Water needs to be “the third or fourth highest-grossing film in history” just to turn a profit.

There is a sense of abandon to all of this, as if filmmakers and studios are just buckling up and leaning into the spin. The proof of this can be found in Hollywood’s recent and renewed embrace of the water tank. Wakanda Forever and The Way of Water — two of the biggest movies of the year — are built around elaborate underwater set pieces. Ryan Coogler even learned how to swim to direct Wakanda Forever, while this was the second time James Cameron almost drowned Kate Winslet.

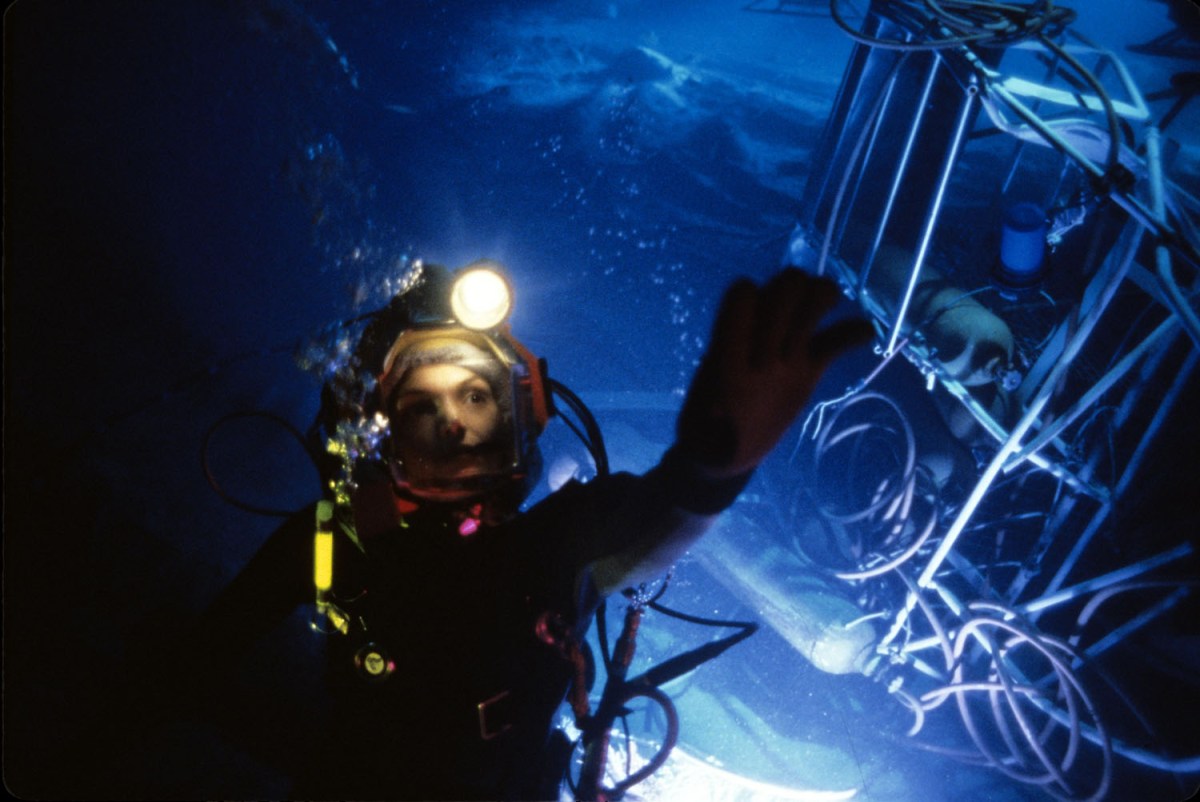

Water tanks are an incredibly dangerous, incredibly laborious, and incredibly expensive part of movie-making. Cameron knows this more than most. His directorial debut was Piranha II: The Spawning, even if he has consistently argued that he’d rather cite The Terminator as his first film. Cameron’s first real experience with big-budget water effects came on The Abyss, the film that he made directly following Aliens.

There was a larger wave of underwater movies during the 1980s, including the two final Jaws sequels, For Your Eyes Only, Never Say Never Again, DeepStar Six, and Leviathan. Hollywood had embraced blockbuster spectacle, and there was a push to ensure that each summer was bigger than the last even though disappointment eventually set in. Budgets soared. Studios chased trends in the hopes of luring moviegoers to theaters, including a miniature revival of 3D during the decade.

These underwater movies may have been part of that larger trend. The Abyss was perhaps the culmination of this push to shoot underwater. It was a famously difficult set. Lead actor Ed Harris accused Cameron of “physical torment,” while his co-star Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio stormed off set declaring that the cast were “not animals.” Cameron faced challenges when several of his set pieces were judged “too dangerous,” while Cameron himself almost drowned.

It is worth stressing here — and this will be a recurring trend — that audiences don’t seem especially enthusiastic about these underwater movies. DeepStar Six and Leviathan were two disappointments in an otherwise impressive summer. The Abyss is easily the lowest grossing of Cameron’s major studio releases. These sorts of elaborate underwater set pieces increase a film’s budget, but these increases don’t necessarily correlate to similar gains at the box office.

Hollywood would shy away from big-budget and high-profile underwater movies for a couple of years, but it would embrace that style of filmmaking towards the end of the 1990s. Once again, it was driven by a game of blockbuster brinkmanship, a sense of escalating scale. By 1997, journalists and analysts speculated that Hollywood was rushing towards disaster with overcrowded summers populated by increasingly expensive movies, threatening to cannibalize each other.

In this climate, it became common for high-profile movies that weren’t even set in aquatic environments to feature elaborate water-based set pieces. The climax of The Truman Show, a film that Paramount pushed out of the overcrowded 1997 blockbuster season in the following year, sends Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey) into stormy waters. Alien: Resurrection stayed in 1997 and featured an especially egregious underwater chase sequence for a movie set in outer space.

![]()

Many of these movies would turn out to be costly fiascos. Kevin Costner effectively ended his movie stardom with Waterworld, a movie that has become a cautionary tale in Hollywood. Even leaving aside the film’s commercial reception, its production was a reminder of the dangers of shooting on and in water. Stuntman Bill Hamilton was almost swept out to sea, while Costner’s stunt double, Norman Howell, suffered a near-fatal embolism while deep sea diving.

Speed succeeded because it was produced on a tight budget. However, director Jan de Bont took the sequel to sea, inspired by nothing more than his own dreams. Speed cost $30 million, with some reports placing Speed 2: Cruise Control’s budget at around $160 million. The sequel’s climax reportedly cost $25 million, or $83,000 per second of screentime. In contemporary interviews, de Bont himself lamented the escalating excesses of blockbuster filmmaking and that movies were becoming “unaffordable.”

This was 1997, the peak of this fixation on underwater filming. Cruise Control released the summer before James Cameron’s Titanic, which attracted headlines for surpassing Waterworld as the most expensive movie ever made. The movie’s production was beset with difficulties. As Fox executive Bill Mechanic confessed years later, “everybody thought the movie was nuts.” Fox was so uncertain about the movie’s viability that Paramount Pictures struck a good deal on its domestic distribution.

Of course, Titanic would defy all expectations. It became a critical and commercial success. It was the highest-grossing movie of all time. However, in the aftermath of the movie’s release, there was a sense of relief within Hollywood. As Mechanic described it, Titanic had “dodged the bullet” of box office failure of other big-budget aquatic epics like Waterworld and Cruise Control, and there was little desire to tempt fate. Rob Friedman at Paramount described it as “lightning in a bottle.”

![]()

It feels appropriate that the big-budget and high-profile water tank movie should make a return a quarter of a century after the release of Titanic. It’s particularly fascinating because this push seems to come from within Hollywood itself. It is not driven by market factors. With notable exceptions like Titanic or even Aquaman, audiences don’t seem to be clamoring for underwater movies. Even Wakanda Forever has underperformed, suggesting audiences aren’t thirsty for this aquatic action.

Of course, it is entirely possible that The Way of Water will be a massive box office success. Only a fool bets against James Cameron, after all. Still, it is interesting that this emphasis on underwater filmmaking seems to develop organically within these studios and among these directors, rather than existing as a trend supported by market data. It often seems like a cinematic Everest, an expensive and risky challenge to surmount largely because it is there.

It can be hard to make an argument for a general “mood” or “vibe” permeating popular culture. Movies are expensive and elaborate objects that are the work of dozens (if not hundreds) of artists developed across years. Richard Linklater, Steven Spielberg, James Gray, and Sam Mendes didn’t sit down together and decide to make semi-autobiographical movies focused on their childhoods to release this year. It just happened that their schedules and creative inclinations aligned.

Still, looking at the films releasing towards the end of the year, there is a palpable sense of indulgence and decadence, spectacle and awe. It is perhaps comparable to the explosion of live-action musicals last year: In the Heights, Dear Evan Hansen, Annette, Cyrano, Tick, Tick… BOOM!, and West Side Story. It’s a reminder of what movies can do. Those auteur biopics speak to the power of cinema on a personal level, but the bigger projects speak to the scale and scope of the medium.

Like those excessive lengths or the indulgent historical accounts of Hollywood’s lost older eras, this dive back into underwater filmmaking is a demonstration of what these films can accomplish at a time when their future seems more uncertain than ever. If Hollywood has that sinking feeling, maybe it makes sense for its directors to take to the water.