This discussion and review contains spoilers for House of the Dragon episode 6, “The Princess and the Queen,” on HBO.

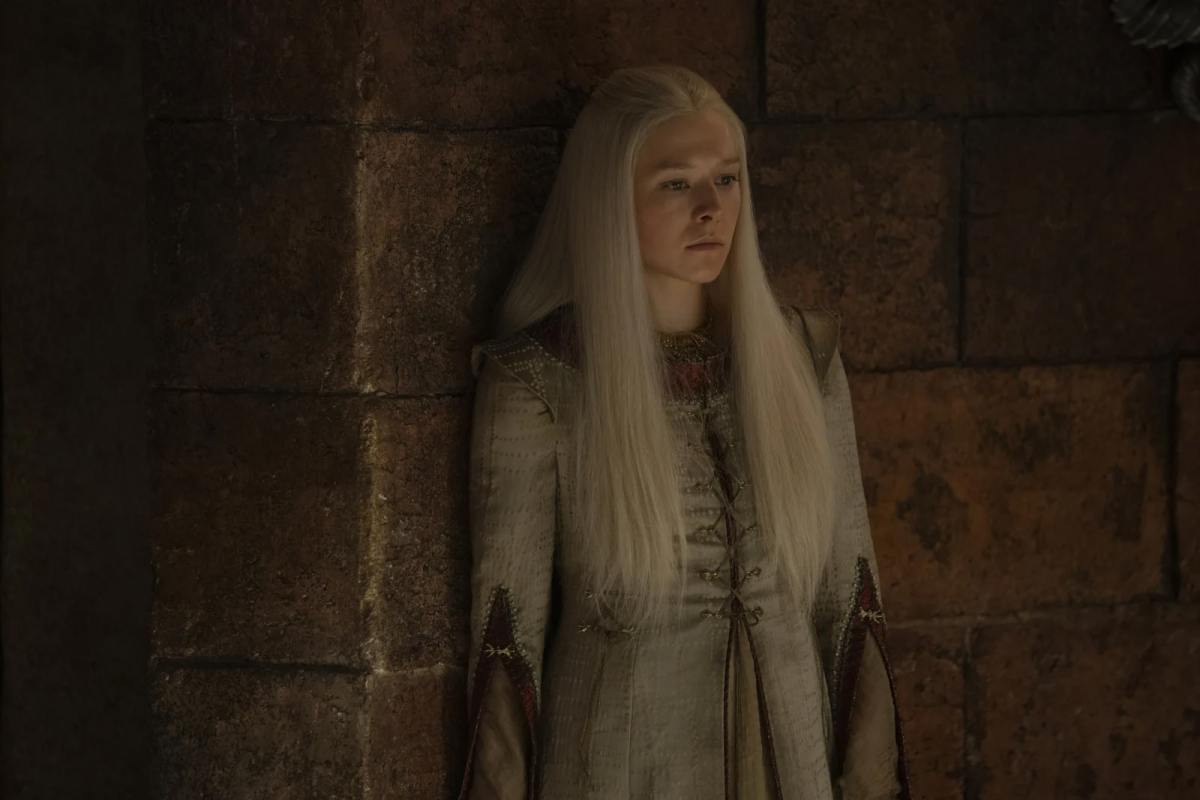

It’s interesting that it has taken House of the Dragon so long to introduce its nominal leads, Emma D’Arcy and Olivia Cooke.

Both D’Arcy and Cooke were part of early casting announcements with Matt Smith. Paddy Considine had been announced a few months earlier, but it would take the production several months to round out its primary cast with actors like Rhys Ifans, Eve Best, Steve Toussaint, and Sonoya Mizuno. Milly Alcock and Emily Carey would be among the last names added to the show’s core ensemble. D’Arcy and Cooke have been the faces of the show, despite not appearing in the first five episodes.

According to D’Arcy, co-showrunners Ryan Condal and Miguel Sapochnik were explicit in approaching House of the Dragon as a story “structured around two women.” Given that the general consensus is that House of the Dragon will run “only three or four seasons,” it is a bold choice to hide the most high-profile actors playing those women until midway through the first season. It effectively renders the first five episodes of the show as an extended prologue to what will follow.

“The Princess and the Queen” jumps roughly 10 years forward in time from Rhaenyra’s (D’Arcy) wedding in “We Light the Way.” While it seems likely that there will be future multi-year time jumps between episodes, just as there were earlier in the season, it is still rather bracing. It is a remarkable statement of intent and a show of confidence from a television series in its first season. It’s also a structural choice that forcefully distinguishes House of the Dragon from Game of Thrones, which refused such time jumps.

However, these time jumps are more than just an aesthetic choice that help to differentiate House of the Dragon from Game of Thrones. They are also an important thematic device. These extended gaps between episodes establish House of the Dragon as a generational saga. After all, Game of Thrones was about a very particular and compressed moment in Westeros’ history, from the end of the reign of Robert Baratheon (Mark Addy) to the destruction of the Iron Throne.

In contrast, House of the Dragon is about history itself. The show unfolds more than a century after the Targaryen conquest of Westeros. Given the premise of Game of Thrones, it spoils nothing to reveal that the reign of House Targaryen will endure beyond the succession crisis presented in the show. It might be weakened and corrupted, but it will survive. This is not a transitional moment in Westerosi history. These characters are all caretakers of an institution much larger than they are.

House of the Dragon reinforces this idea in a number of ways. The time jumps within the narrative are one example, reassuring the viewer that events have not yet built to such a critical mass that every decision and every moment matters. The way in which the show is haunted by Game of Thrones is another. The prophecy of “the Song of Ice and Fire” reminds audiences that these families and this throne will continue on for centuries beyond the events unfolding.

Even beyond this, House of the Dragon is a generational saga in the most literal manner imaginable. House of the Dragon is a story about how the Targaryen line will continue. It is about who will follow King Viserys (Considine) on the Iron Throne. Whether it is his daughter Rhaenyra, his brother Daemon (Smith), or his son Aegon (Tom Glynn-Carney), a Targaryen will sit upon the Iron Throne. For all that House of the Dragon draws upon the real-world history of “the Anarchy,” order will prevail.

There is an interesting existential anxiety that pervades House of the Dragon. Much of the core cast seems actively frustrated by the relative stability of the realm. In “The Heirs of the Dragon,” Rhaenys (Best) mused at all the pent up frustration from decades of peace, spilling over into violence and bloodshed at the first opportunity. The men of House of the Dragon seem anxious to be living in times of peace and prosperity.

Laenor (John Macmillan) is excited by the prospect of a distant war in the Stepstones. “War is afoot again in the Stepstones, Rhaenyra,” he boasts. “The Triarchy takes new life from its alliance with Dorne.” He plans to run off to fight in the conflict. “After all this time, this is just what I need. A little adventure. A good honest battle to enliven my blood again.” War is a distraction, one that might provide an escape from the comfortable and privileged life that Laenor enjoys.

Similarly, Daemon is living a comfortable life in exile but also feels the intoxicating pull to a foreign war. When the Prince of Pentos (TBD) asks Daemon to involve himself in the fight against the Triarchy, Daemon is tempted. “A simple transaction: we have dragons, they have gold,” he explains to his wife, Laena (Nanna Blondell). The lack of stakes draws Daemon to the idea. “We are without responsibility. Political scheming, the endless shifting of loyalty and succession — none of ours.”

House of the Dragon explores the sense of what it means to be passengers of history, rather than its driving forces. It is debatable how much agency the characters exert from within the narrative. Laena and Daemon are “eternally guests” of Pentos, but it is questionable how much more power they would hold in King’s Landing. The healthy functioning and perpetuation of the state reduces all its players to pawns. For men, this leads to boredom. For women, it is much worse.

House of the Dragon places an emphasis on birth, and the show’s portrayal of the ordeal and the suffering of women resonates with the current political climate. Although the first season was written and filmed before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Sapochnik acknowledges that the forced birth scene in “The Heirs of the Dragon” felt “more timely and impactful than ever.” Birth becomes an act of violence, as a woman’s body is rendered subject to the needs of the state.

House of the Dragon is about the women who shoulder the burden of maintaining this generational dynasty and the march of history, often against their own will and with minimal agency. “The Princess and the Queen” establishes that the forced birth sequence in “The Heirs of the Dragon” was more than just a shocking set piece. It was a statement of purpose. After all, “The Princess and the Queen” is itself bookended with two more brutal birth sequences, establishing pregnancy as one of the season’s central preoccupations.

Pointedly, “The Princess and the Queen” opens with Rhaenyra’s third birth. This establishes a very pointed parallel with her mother, Aemma (Sian Brooke), who died during her third birth in “The Heirs of the Dragon.” Rhaenyra survives, but it is by no means a pleasant experience. The sequence in which Laenor accompanies his wife to meet Queen Alicent (Cooke) plays as pitch black comedy, as he tries to awkwardly express sympathy for the ordeal that Rhaenyra has just endured.

“Was it terribly painful?” he asks. He tries to relate to her suffering, “I took a lance through the shoulder once.” The two bicker briefly over the naming of the child. “He’s our child, is he not?” Laenor asks. Rhaenyra pointedly responds, “Only one of us is bleeding.” To Laenor’s credit, that at least seems to settle the argument. Indeed, Laenor’s most insightful statement is perhaps his most simple, as he concedes, “I am glad I am not a woman.”

Of course, the saddest aspect of all of this is that Joffrey’s birth is presented as something of an ideal. Both mother and child survive. Although she is in agony, Rhaenyra is able to at least heed Alicent’s summoning. It’s brutal and horrific, but this appears to be the best-case scenario. It is certainly preferable to the ordeal experienced by Laenor’s sister Laena, who endures a birth so agonizing that she decides to be burnt alive by her dragon rather than suffer further.

“The Princess and the Queen” makes a rather barbed and pointed parallel here. Birth is horrific and violent, but the show also seems wary of progeneration in general. In a very real way, children are often the deaths of their parents. The women who die in childbirth are just the most literal example of this, but all children are essentially created as replacements for their parents. They are reminders of mortality. They are the embodiment of their parents’ obsolescence.

Laena’s death by fire following a botched birth is neatly echoed with the murder of Lyonel Strong (Gavin Spokes) as Harrenhal burns down. Like Laena, this is a fire that consumes both parent and child. Lyonel burns alongside his eldest son Harwin (Ryan Corr). However, there is a much darker irony at foot here, as the fire was masterminded by his younger son, Larys (Matthew Needham). In House of the Dragon, procreation is an act of horror.

“What are children but a weakness, a folly, a futility?” Larys muses through voiceover. “Through them, you imagine that you cheat the great darkness of its victory. You will persist forever in some form or another, as if they will keep you from the dust. But for them you surrender what you should not. You may know what is the right thing to be done, but love stays the hand. Love is a downfall. Best to make your way through life unencumbered, if you ask me.”

Here, again, there are echoes of Game of Thrones. “Winter Is Coming,” the first episode of Game of Thrones, ends with Jaime Lannister (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau) ironically declaring, “The things I do for love,” before pushing Bran Stark (Isaac Hempstead Wright) out of a tower window. House of the Dragon suggests that the real horror is what the people we love might do to us.