Everyone agrees that Thief: The Dark Project was important. It helped to establish stealth games and immersive sims, demonstrated new ways to integrate world-building and narrative, and was one of several titles that showed that first-person games didn’t have to fit the mold of Doom or Ultima. What not everyone might realize is that Thief was also at the forefront of a new genre of speculative fiction: what’s come to be known as the New Weird.

The New Weird emerged in the 1990s, pioneered by writers working at the intersection of science fiction, fantasy, horror, and other literary movements, and under influences as diverse as H. P. Lovecraft, Mervyn Peake, Ursula Le Guin, and Philip K. Dick. The watershed moment was arguably the publication of China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station in 2000 and Jeff VanderMeer’s City of Saints and Madmen in 2001, but the moniker “the New Weird” did not appear until 2002. By the 2010s the New Weird had found more mainstream success, with adaptations of Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, China Miéville’s The City & the City, and last year’s release of Control.

There is an argument that the New Weird is less a coherent genre and more a banding together of writers who reject the traditional tropes of speculative fiction — wise wizards, mysterious elves, utopian technology, space travel, etc. — in favor of unusual forms and narrative elements. However, if we follow Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s anthologies The Weird and The New Weird and look at some of the themes that recur most often in New Weird mainstays, like the aforementioned Perdido Street Station and City of Saints and Madmen, we can identify a few relative commonalities.

First, the setting is often urban and early industrial, typically a large city or similar. Second, the stories are usually about the interplay of the personal with the social or the political: anguish, madness, obsession, ambition, conspiracy, exploitation, marginalization, and so on. When creating the metropolis of New Crobuzon, Miéville said that he wanted to deliberately subvert the pre-industrial heroic tropes of fantasy fiction and supplant them with something more akin to our messy and complex reality. Third, and by extension, the tone is dark and unsettling. Deviations from this are typically of degree, rather than type.

For anyone who knows Thief, I think the affinities should be obvious. It takes place somewhere simply called The City, a sprawling metropolis that seems to be trapped between medieval and industrial ages. There are steam engines alongside swords and arrows, electric cables alongside candles and torches, machine worshippers alongside pagans, and crime syndicates alongside secretive scribes with supernatural powers. It has been described as steampunk, but it has too much of the medieval to fit comfortably into that bracket (and in any case, there is no hard line separating the New Weird from steampunk) and too much modern technology to fit into traditional medieval fantasy.

The story follows Garrett, a master thief, who is hired by a strange couple, Viktoria and Constantine, to steal a mysterious artefact. As events unfold, it becomes apparent that Garrett’s contract is deeply intertwined with the religions, customs, and politics of The City and affects all of its main factions. It also becomes clear that Viktoria and Constantine are hiding something. Their secret is revealed through a stylized, part-drawn, part-rotoscoped cutscene that builds a feeling of dread with its art, dialogue, and soundtrack, a mix of ambience and industrial synths that is a far cry from the orchestral scores associated with traditional fantasy.

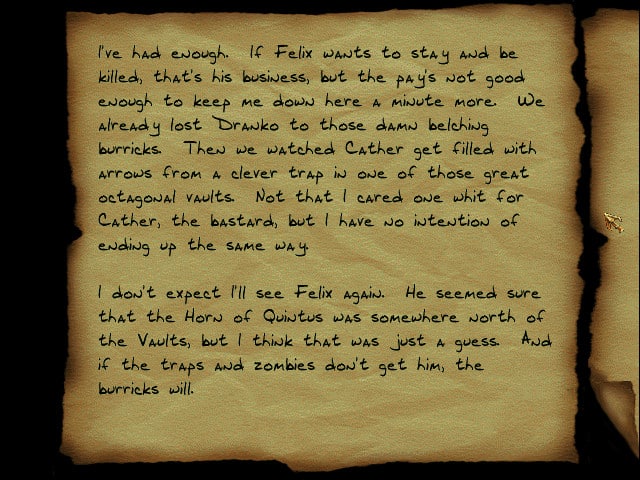

And then there is Thief’s general tone and ambience. The game is dark in the literal sense — every level and cutscene takes place at night — but the muted palette underscores a more general sense of oppression. The architecture seems to crowd in on the player. The streets are sometimes suffused with the industrial hiss and clang of The City, but at other times they are eerily quiet, disturbed by the odd whistle or a curse in a local dialect. The characters, not least Stephen Russell’s sly, misanthropic portrayal of Garrett, are by and large either simpletons or cynically self-interested. There are no heroes or valiant nobles, and Garrett’s eventual role as the savior of The City is necessitated by his own errors.

In short, Thief’s setting, characters, and tone do not fit comfortably into any traditional genre of speculative fiction. Looking back, perhaps this was to be expected. To my knowledge the writing team has not cited the influence of weird fiction. However, behind-the-scenes features show that at one point the game was penned as a deliberate subversion of Arthurian legend — the original medieval fantasy. So from early in its development cycle — even before the final setting, characters, and narrative were settled — Thief shared its goals with the New Weird: to subvert the tropes of traditional fantasy with something dark and unexpected.

Thief entered development in early 1996, four years before the New Weird hit the “big time” and six years before the genre got its label. The Dark Project was a contemporary of Miéville’s and VanderMeer’s earliest stories, as well as of many other writers unable or unwilling to make their work conform to norms (including Marc Laidlaw, who would later come to write Half-Life). That puts it squarely at the forefront of the New Weird — not merely as something influenced by the genre, but a constitutive element of its first wave.

It also suggests that Thief’s influence on the video game medium extends beyond its considerable innovations in gameplay design. Thief’s New Weird sensibilities are perhaps most obvious in the Dishonored series (which even borrowed Stephen Russell’s voice for the second installment). Although Dishonored’s Dunwall and Karnaca — with their use of electricity, mechanized weapons, and gunpowder — are more straightforwardly steampunk than The City, they are also under the influence of a deity known as The Outsider and his dark and mysterious magic, which keeps the settings uncanny. Thief’s New Weird DNA is also found in BioShock, BioShock 2, and BioShock: Infinite, which put their strange urban settings, bizarre biotechnology, and unconventional storytelling front and center (unsurprising, given that Ken Levine worked on both Thief and BioShock).

There are less obvious instances of Thief’s New Weird influence too. For example, there is a clear family resemblance between Thief and The Elder Scrolls series, and I would not be the first to argue that Morrowind is another instance of the New Weird genre. There is a hint of Thief’s City in the alternate history of Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate, more than a hint in Seven: The Days Long Gone, and even in something as singular and original as Pathologic, which is set somewhere simply called The Town. (In fact, Pathologic is originally written in Russian, and the Russian word for “town” may also be translated as “city.”)

The point is that, however strict or liberal we want to be with what we countenance as influence, Thief has influenced not just how games are designed from a systems perspective, but how dark, strange, and experimental games can be in their choice of characters, setting, and tone. The fact that Thief arrived in 1998 means that it was one of the first to do so, way before it was cool.