At its core, Barry is a show about whether an individual can ever truly escape their past and what redemption might actually look like.

Creators Bill Hader and Alec Berg had been put in contact by their mutual agent, with Hader wanting to build a show around the anxiety that he felt working on Saturday Night Live as “a prisoner of his own talent.” Those early meetings were fruitless. Hader recalls latching onto the show’s premise in a moment of desperation, “At the end of two months we said, ‘This idea is terrible, let’s not do this.’ And out of frustration I said, ‘What if I was a hitman?’”

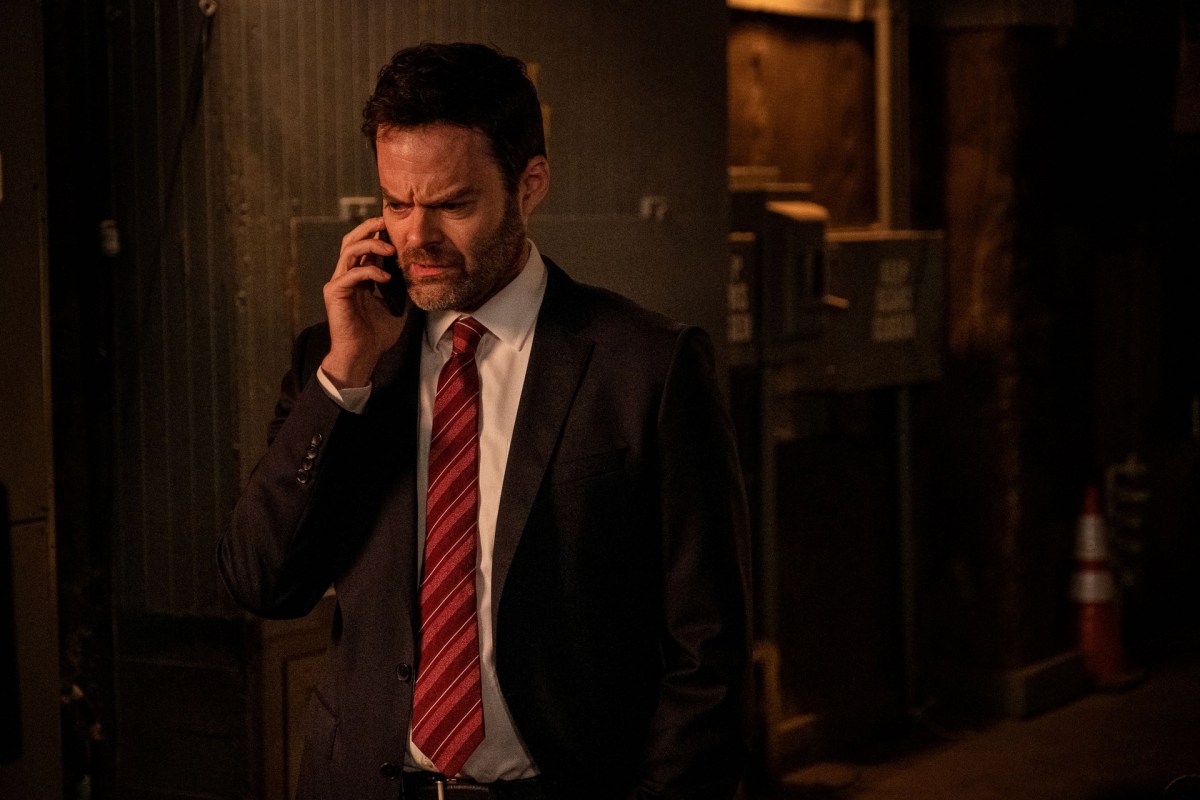

Berg was reluctant, finding the idea hackneyed. “I hated that idea,” he admitted. “There are more hitmen on TV and in movies than I think there are in real life, probably.” Still, that was the key. Barry became the story of Barry Berkman (Hader), an assassin trying to reinvent himself as an actor in Los Angeles. There’s a tension that feels very specific to Los Angeles — the juxtaposition of the city’s twin obsessions: gritty crime story and celebrity fairy tale.

Hader was inspired by a set visit to Better Call Saul, and Barry feels like a companion piece to that epitaph for the archetypal television antihero. Certainly, Barry’s career as a murderer for hire places him in the larger context of television’s “difficult men,” from Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) to Vic Mackey (Michael Chiklis) to Walter White (Bryan Cranston). He is not too far removed from Los Angeles fixer Ray Donovan (Liev Schreiber).

However, Barry is surprisingly disinterested in the title character’s violent profession. Of course, the show uses Barry’s profession as a framework for some of the best action sequences on television. However, Barry is just inherently good at what he does; he doesn’t seem to derive any joy from the act and is rarely in any true peril. In fact, Hader contends the show is about “the idea of being very gifted at something you derive no pleasure from.”

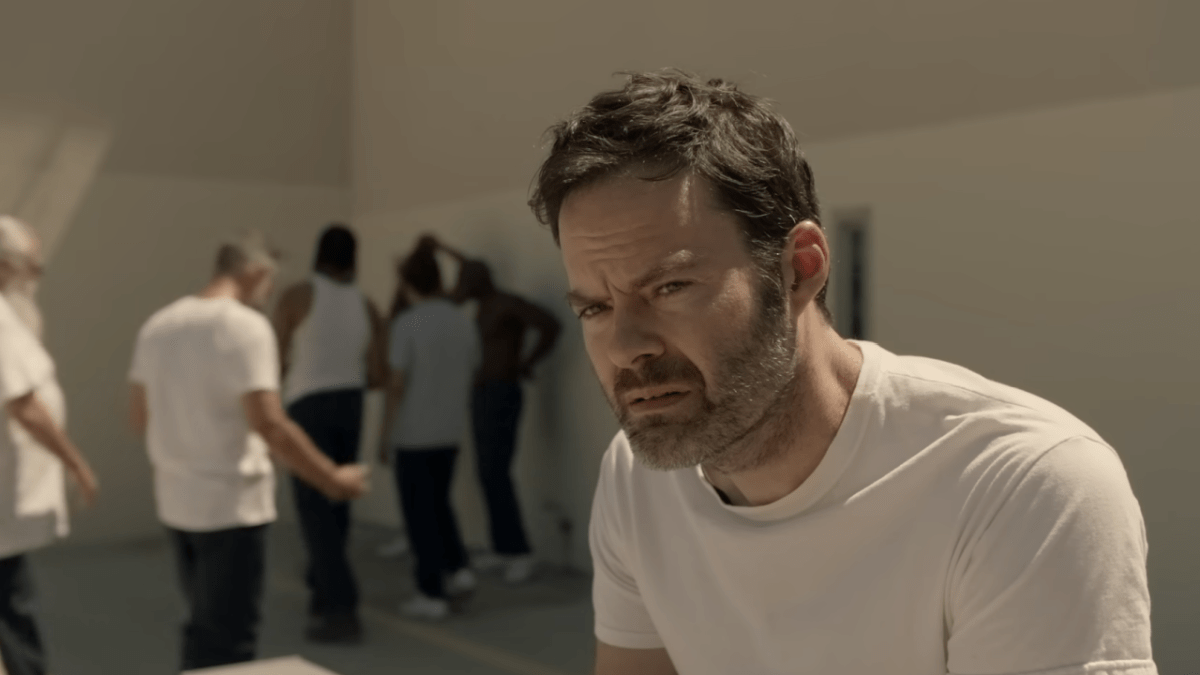

For Barry, the stakes aren’t rooted in the ongoing gang warfare subplot involving competing Chechen, Burmese, and Bolivian interests in the city’s heroin trade. Barry dispatches armies of henchmen without breaking a sweat. He’s ruthlessly efficient in dealing with any perceived threat. In the first season, he murders both fellow veteran Chris Lucado (Chris Marquette) and Detective Janice Moss (Paula Newsome) when they risk exposing him.

There is a sense that Barry’s day job could be anything. He is only a contract killer because he has skills that he honed in military service, and family friend Monroe Fuches (Stephen Root) recognized the opportunity to make money off the veteran’s uncanny abilities. There’s a sense that Barry really just wants to belong, to share a human connection. Throughout the show’s run, Fuches manipulates the young man by appealing to his sense of “purpose.”

During the second season, talking candidly about the first time he took a life, he describes it as “the best day” of his life not due to the act itself but because the celebrations of the troops around him gave him “a sense of purpose, a sense of community.” Barry finds that purpose and community in Los Angeles, when he is hired to kill aspiring actor Ryan Madison (Tyler Jacob Moore). Barry infiltrates Ryan’s acting class and almost immediately connects to it.

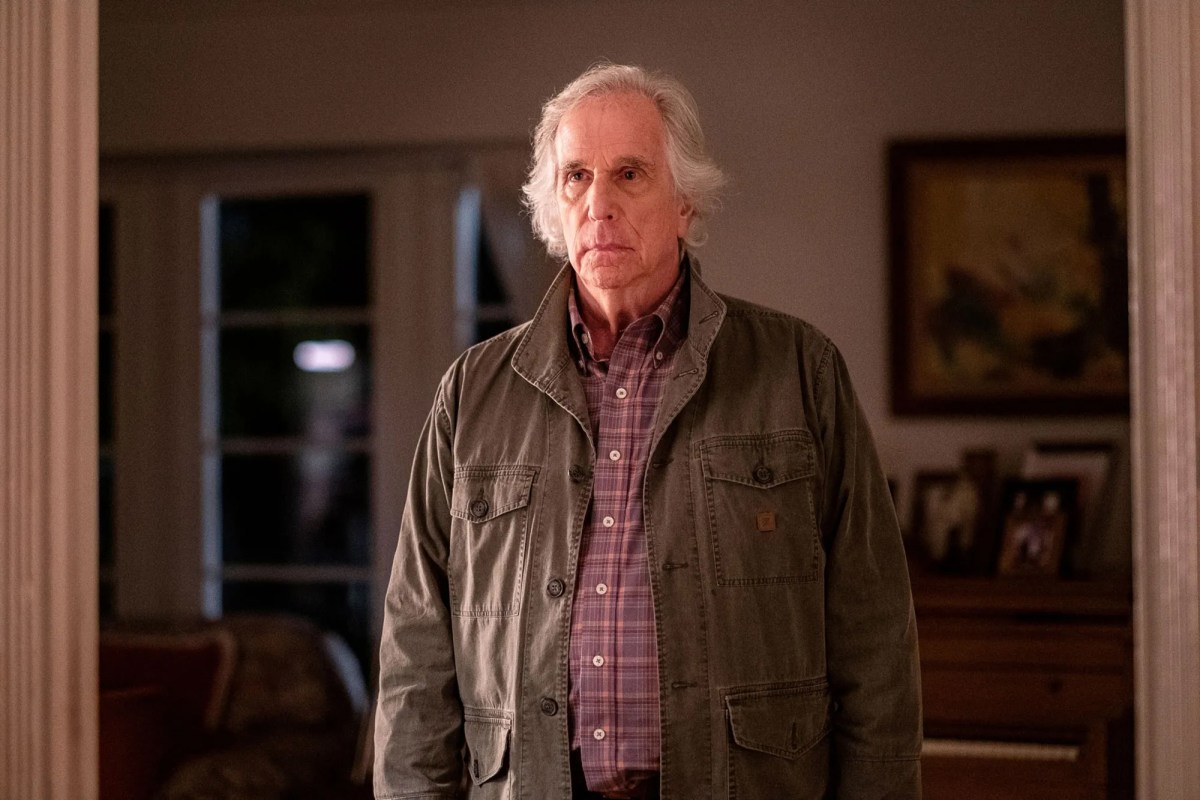

Throughout Barry, the greatest threats to the character derive from his pursuit of acting as a career — his attempt to reinvent himself as “Barry Block.” He finds a surrogate father figure in teacher Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler) and starts a relationship with his classmate Sally Reed (Sarah Goldberg). Berg noted the irony of this contrast between Barry’s twin realities, “The crime world has very, very high stakes but very low drama. While the drama world is very, very low stakes but very high drama.”

For Barry, acting is a fresh start. He internalizes this idea from Gene. “He said I can change my nature,” he tells Fuches. “That means that I can own all this stuff that we’ve been talking about. All these things that I don’t like about myself, that I can own them, and they don’t define me.” Barry doesn’t know who exactly he wants to be — early on, he buys an outfit because he “went to J.Crew, and (it) was on the mannequin” — simply that he doesn’t want to be himself.

This is a quintessential Los Angeles story. The central myth of the American West is one of reinvention and renewal. As Michiko Kakutani contended, “The prospect of reinventing oneself tabula rasa has always been one of America’s foundation myths.” On the frontier, there is no past. As Hans R. Guggisberg wrote, “In the West, American history had found a new beginning.” In some ways, Hollywood is the endpoint of this philosophy.

Barry is a show about a literal murderer, but it is somehow more cynical about show business. This plays out in subplots about the inner workings of the industry, of streaming metrics and algorithmic programming. However, it also plays out in a more fundamental way. Barry is wary of acting and storytelling as activities of themselves, arguing they can serve as barriers that prevent individuals from meaningfully confronting the consequences of their actions.

In the second season, Gene tries to reconnect with his estranged son, Leo (Andrew Leeds). Discussing their history, Gene hides behind the language of his trade. “I did what every great actor does — I improvised,” he admits. Leo replies, “You left.” Gene concedes, “Look, you want to leave them wanting more, not less.” It seems that Barry himself is drawn to acting because it allows him to pretend to be somebody other than who he knows himself to be.

Throughout that season, Gene encourages his class to write and perform psychodramas drawn from their own history, “moments from (their) own lives that help shape and define (them).” This requires honesty from the performers. Gene urges Barry to tell a personal story from his service. Sally decides to tell the story of her decision to leave an abusive relationship with her ex-husband Sam (Joe Massingill). These are very raw and personal stories.

It quickly becomes clear that Barry and Sally cannot tell their stories. Sally commits to telling the sad story about how she sneaked away while Sam was passed out drunk, but then rewrites history to give herself an empowering moment of standing up to her abuser to make her story more triumphant and marketable. Barry contemplates telling a story about his murder of an innocent civilian during the Afghanistan War. Gene shuts the idea down, warning him, “You never tell that story again as long as you live.”

During that second season, both Barry and Sally are warned that “everyone’s a hero of their own story, right?” In both cases, that admonishment comes from an abuser, Barry’s exploitative manager Fuches or Sally’s ex-husband Sam. Still, there is truth to it. Unable and unwilling to confront the truth of their own pasts, fabricating self-serving mythologies for public consumption, both Sally and Barry find themselves unable to move forward.

When Janice tries to arrest Barry in the first season finale, he attempts to reason with her. “We want the same thing,” he tells her. “We want to be happy. We want love. We want a life. And we’re doing it, Janice. We’re the same.” It’s a comforting lie, but Janice sees through it. “But we’re not,” she explains. “We’re not the same, Barry. ‘Cause I’m a cop. And you’re a fucking murderer.” Barry murders Janice to preserve his life with Gene and Sally.

Hader argues the third season is about the idea that “forgiveness has to be earned.” Throughout the season, characters try to get past the things they’ve done. When Gene discovers Barry killed Janice, Barry tries to make it up to his teacher by resurrecting his career. When Gene feels guilty about his complicity, he tries to pay it forward by reviving the career of his ex-girlfriend Annie (Laura San Giacomo), whom he “blackballed” out of spite.

Gene is self-centered and arrogant, but he makes a more genuine effort at atonement than Barry. He even apologizes to a writer (Michael Lanahan) that he assaulted on Murder, She Wrote. Still, Annie doesn’t believe that Gene’s atonement is entirely selfless. “I don’t think that you’re really apologizing for us,” she explains. “You’re just saying that so you don’t have to feel bad anymore.” Gene is an actor; even his attempts at apology are a performance.

It makes sense that Barry engages with the challenge of reconciliation. Even within the entertainment industry wherein the show is set, there is an ongoing reckoning over decades of abuse. There are debates about how guilty parties can atone for past actions. The parallel is intentional; late in the season, Sally has to make her own celebrity apology. There’s also a larger cultural reckoning taking place in America concerning historical injustices.

Still, Barry pointedly rejects the idea of violent retribution as a satisfying resolution. When the wife (Annabeth Gish) of one of Barry’s early victims plans to murder him in retaliation, the gun accidentally goes off, shooting her son (Alexander MacNicoll). Twice in the third season, Fuches finds “a little slice of heaven” in a picturesque rural setting, only to give it up in his pursuit of vengeance against Barry for a perceived wrong. He’s trapped in a bitter cycle.

The third season of Barry moves in circles. The fourth episode replays the teaser to the show’s very first episode from a different perspective. The season opens with Barry supervising the digging of a grave in the shadow of a single tree in the desert, and he returns to that bleak setting in the season finale — “windswept desert, lonely Beckettian tree.” There’s a sense of grim tragedy and eternal recurrence to this. Barry cannot move forward. At the end of the season, Sally boards a plan for Joplin, the hometown she escaped.

Perhaps the only person in Barry who attains a state of grace is George Krempf (Michael Bofshever), the father of Ryan Madison, the actor Barry was hired to kill. George finds Barry, who has been poisoned by Chris’ wife, Sharon (Karen David). George considers letting Barry die. “I could leave you here, and you’ll rot,” he admits. “But I can’t. Why? I want to see my son again.” George drives Barry to a hospital. Having saved the man he blames for his son’s death, George takes his own life. It’s heartbreaking and grim.

In some ways, Barry feels like the culmination of decades of antihero shows from The Sopranos to Breaking Bad, albeit one more directly interested in the legacies of these violent and brutal actions than in the immediacy of the acts themselves. Barry suggests that redemption lies beyond human comprehension, while also suggesting that the inability to reconcile with the past will only cause violence to recur and self-perpetuate. Nobody can outrun the past; they can only reckon with it as best they can.

No amount of Hollywood make-believe can change that.