Batman has one of the finest and deepest rogues’ galleries in comics. It’s difficult to imagine Sinestro or Black Manta carrying a billion-dollar hit like Joker. These foes are rich and complex, providing a fractured mirror to the Dark Knight. With the release of the teaser for Matt Reeves’ The Batman, it looks like the Riddler might be getting a shot at the spotlight.

The Riddler is one of Batman’s most compelling antagonists, both because of what he represents within the narrative framework of Batman’s universe and because of what he embodies outside of it. The Riddler is one of the most recognizable Batman villains, but he has been entirely absent for extended periods of Batman’s history. As a result, the Riddler feels contradictory, essential to the Batman mythos while often struggling to find a place within it. He is a puzzle piece that doesn’t fit.

Unlike classic characters like the Joker or the Penguin, the Riddler was not a consistent fixture of the Caped Crusader’s early years. In fact, the Riddler would only appear twice during the Golden Age of Comic Books. He appeared in two issues of Detective Comics in October and December 1948 and then vanished. He might have remained lost, if not for a one-shot appearance in an issue of Batman in May 1965 during Batman’s so-called “New Look” era of the early Silver Age.

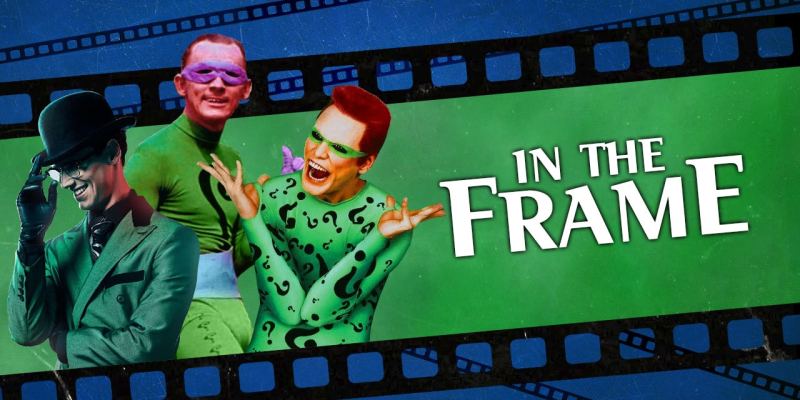

“Remarkable Ruse of the Riddler!” was not a particularly notable story in itself, but it was hugely influential, serving as the basis for the pilot of the live-action Batman series that would launch in January 1966. The show would launch with a loose two-part adaptation of the story in “Hi Diddle Riddle” / “Smack in the Middle,” casting impressionist and comedian Frank Gorshin in the role of the Prince of Puzzlers.

The Riddler would become perhaps the biggest breakout hit from Batman. Gorshin would earn a Primetime Emmy nomination for his appearance in the pilot. Although the producers reportedly always kept a script ready for Burgess Meredith whenever he was available to play the Penguin, Gorshin would become the most frequently recurring villain in the show’s first season. He appeared in eight of the season’s 34 episodes. Gorshin also gave him a kick-ass theme song.

Gorshin’s performance was revelatory. It remains one of the best supervillain performances in the history of the genre. He played the Riddler in a style very much in keeping with the camp aesthetic of the show around him, but with a layer of menace simmering beneath the megalomania. Gorshin played the role at extremes. The Riddler often vacillated between screaming and growling, balanced on a knife edge between exploding and imploding.

In the 1966 film, the Riddler is portrayed as unstable to the point that he seems to genuinely worry his villainous collaborators. The Joker (Cesar Romero) of all people declares, “You’re mad, Riddler.” Still, even in that camp setting, the character exudes a strange pathos. When the Joker points out that leaving Batman clues will inevitably lead to their defeat, the Riddler admits he cannot help it: “Oh, outwitting Batman is my sole delight, my joy, my heaven on Earth, my very paradise!”

In hindsight, the success of Gorshin’s characterization of the Riddler would be a mixed blessing for the character. Gorshin’s performance ended up profoundly affecting how later stories would approach many of Batman’s other villains. In the decades that followed, more and more of the Caped Crusader’s antagonists would be portrayed as volatile and pathological – figures at once trapped by their compulsions and prone to dramatic mood swings.

This is perhaps most obvious with the later characterization of the Joker. Cesar Romero played a surprisingly gentle version of the Clown Prince of Crime, keeping with the character’s portrayal in the contemporary comics. In the movie, the Joker actively comforts the Riddler. In contrast, the mad cackling and demented intensity of Jack Nicholson and Mark Hamill’s Jokers is closer to Gorshin’s Riddler. Even Heath Ledger’s Joker alternates between loud and quiet to similar effect.

While this undoubtedly made the Riddler less unique, Gorshin’s performance established the character’s place among Batman’s core villains, an impressive feat for a foe who had only made three comic book appearances before the show. The Riddler would appear six more times in the comics while Batman was on the air and once more a few months after it was canceled. After that, the character would disappear for a full seven years before returning in May 1975.

Writers often struggled with how best to handle the Riddler, with stories like The Long Halloween treating the character more as a curiosity than a threat. The character zigged and zagged in various directions over the years that followed; he deduced that Bruce Wayne was Batman in Hush, got bonked on the head and forgot it in Infinite Crisis, and reinvented himself as a private detective in Paul Dini’s underappreciated Detective Comics run.

Theoretically, the Riddler provides an intellectual foil to Batman. He sets challenges that the Dark Knight cannot overcome with brawn alone. Batman debuted in a series titled Detective Comics, and a lot of his brand is built around his persona as “the world’s greatest detective.” Of course, it’s highly debatable to what extent “Bat-deduction” is a true measure of the character’s detective prowess. Still, the Riddler presents an intellectual rather than a physical threat to Batman.

However, the Riddler often works best as an avatar of the Silver Age, as the villain who had most obviously thrived in the colorful surroundings of the 1960s series and most definitely struggled afterwards. In Secret Origins Special in 1989, Neil Gaiman and Bernie Mireault presented the Riddler as a weirdo living in a junkyard of oversized novelty props, lamenting, “It’s all different. It’s all changed. The Joker’s killing people, for God’s sake! Did I miss something?”

Some of the character’s best stories use the Riddler as an avatar of the Silver Age in a way that is deliberately unsettling. In Peter Milligan and Kieron Dwyer’s “Dark Knight, Dark City,” published at a time when comics were becoming “grim and gritty” after the success of Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, Batman confronts a series of uncharacteristically grotesque crimes orchestrated by the Riddler. “The Riddler’s changed,” Batman muses. “Become a psycho.” One of the Riddler’s goons suggests, “Maybe it’s mid-life crisis or sumthin’.” (It turns out to be demonic possession.)

That was a time when fandom was very insecure about the campiness of the Batman 1960s series and its legacy for the Caped Crusader. Perhaps the Riddler suffered from some of those associations, as he was more closely tied to the 1960s series than any other major Batman villain. Of course, it’s possible to overstate the extent of this backlash. Batman Returns was many things, including an update on the classic two-parter “Hizzoner the Penguin” / “Dizzoner the Penguin.”

Still, this association can carry with it some discomfort. In Batman Forever, Jim Carrey plays the Riddler as the embodiment of camp. He is a living cartoon character. In an interesting mirror of his work in The Cable Guy, Jim Carrey presents the Riddler as a jilted lover who is obsessed with Bruce Wayne (Val Kilmer). He sends Bruce enigmatic “love letters,” models his physical appearance on the billionaire bachelor, and even literally tries to get inside his opponent’s head.

Batman Forever is ultimately about asserting Bruce Wayne’s heterosexuality. Even in the movie’s cartoonish surroundings, the Riddler’s campiness is presented as a threat that needs to be vanquished so that Bruce can form something resembling a conventional family unit with Chase Meridian (Nicole Kidman) and Dick Grayson (Chris O’Donnell). Still, it is notable that the Riddler is the first true villain in the Burton/Schumacher films series who doesn’t die. He survives, defeated but not obliterated.

The Riddler is arguably more important as a symbol than a character. Following the Flashpoint reboot, writer Scott Snyder and artist Greg Capullo would establish the Riddler as one of the first supervillains to menace Gotham in their “Zero Year” arc. While the Joker occupies pride of place among Batman’s villains, it makes sense for the Riddler to serve as primary antagonist in Matt Reeves’ The Batman, as a story about “the origins of a lot of our Rogues Gallery characters.”

Much has been written about the perceived darkness of the live-action Batman movies, especially since Batman Begins brought new psychological complexity to the character. While such criticisms largely discount the brighter interpretations of the character in films like The Lego Batman Movie or shows like The Brave and the Bold, The Batman looks to be offering a particularly brutal and violent take on the character.

It seems appropriate that the Riddler should manifest as a foil to this version of the character, offering riddles that read like accusations. “If you are justice, please do not lie.” The Batman trailer suggests an interesting approach to the Riddler, with Paul Dano bringing all the intensity of the actors influenced by Gorshin back to the character while presenting him as an existential challenge to the Caped Crusader.

There is something strange in placing the avatar of the campy Silver Age in the middle of a trailer that takes its cues from David Fincher’s serial killer thriller Se7en. However, that dissonance gets to the heart of what makes the Riddler so compelling. Amid these contradictions, he asks the questions that haunt the Knight.