With the release of Knock at the Cabin last weekend, it seems like a good opportunity to talk about M. Night Shyamalan films and their relationship with faith. Be warned, this article contains spoilers for many of Shyamalan’s films.

It is perhaps an understatement to argue that M. Night Shyamalan’s movies are fascinated by faith. It might be more accurate to say that they are terrified by the prospect.

Shyamalan does not believe in any particular religion. “I’m not religious at all,” he told The New York Times in the lead-up to the release of Glass. “I have my issues with the specificity of organized religion and the tribalism that that conjures, but I am somebody who really believes in whatever you want to call it, the universe and our place in it.” However, despite his lack of religious belief, Shaymalan was raised in two different religious belief systems.

“My parents are Indian, I was raised Hindu,” Shyamalan has explained. “You know, if I went to my grandmother’s house in India, there would be a chicken head nailed to the tree right outside. And I’d ask her what that was and she would answer, ‘To keep away the ghosts.’ [Laughs] It was like, ‘Oh, alright.’” However, Shyamalan moved to Philadelphia as a child, where he was — by his own account — the “only Hindu in Catholic School.”

Shyamalan has acknowledged that this informs a lot of his work, even if he doesn’t believe in either. “It gave me a kind of a perspective on both religions, Hinduism and Catholicism(,) and that made me think a lot about spirituality in general,” he stated. “So I think if I had gone to a public school or if my parents hadn’t been religious then maybe those questions wouldn’t constantly emerge in what I sit down to write.” These themes play through his filmography.

Shyamalan is quite candid about the influence of these beliefs on his films. “I guess I’ve grown up in both Catholic and Hindu religions, where water is so critical,” Shyamalan explained of the water imagery that occurs in movies like Unbreakable and The Lady in the Water. “It could purify you and be a symbol of rebirth and renewal and starting over, or it’s so powerful it could just eradicate you.” In Knock at the Cabin, the first sign of a looming apocalypse is a massive tidal wave.

Most of Shyamalan’s films could be classified as horror or thriller, suspense-driven narratives in which the director is constantly escalating the tension. Shyamalan often ratchets up suspense by introducing a character (or a group) with a set of irrational beliefs, building narrative tension around the lengths to which these people will go in service of their faith and the possibility that these seemingly illogical ideas may ultimately be correct.

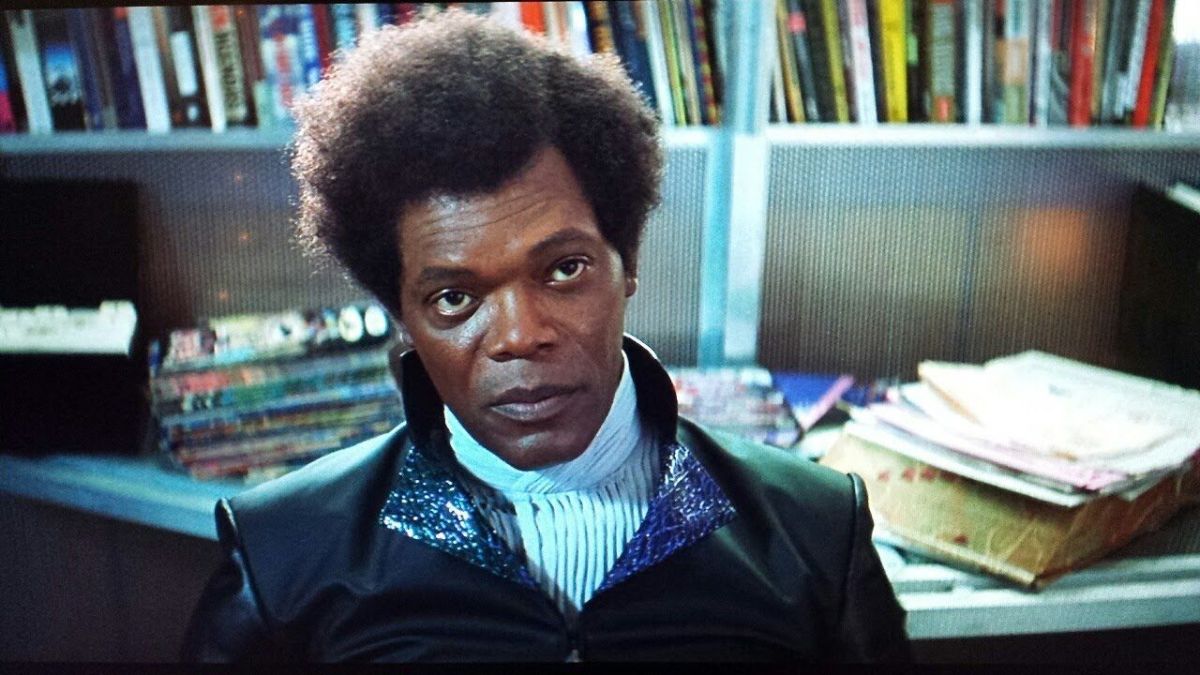

This faith isn’t always religious in nature. In Unbreakable, David Dunn (Bruce Willis) lives through a horrific train crash. Looking to find some explanation for his miraculous survival, David comes into contact with a comic book obsessive named Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson), who is convinced that superheroes really exist. David is initially skeptical but finds himself gradually convinced by Price’s unwavering certainty.

However, David eventually discovers that Price is so devoted to his belief in the existence of superheroes that he engineered a number of mass tragedies — including the train crash — to prove his theory correct. Price is ultimately confined to a psychiatric institution for his crimes and is declared criminally insane. However, there is a lingering and unsettling implication that he was ultimately correct in his beliefs: David is a superhero, and Price did find him.

This is a fairly universal fear that permeates a lot of horror movies, the anxiety that the world may not be as rational — and therefore as predictable — as people would like to believe. In Split, Kevin Wendell Crumb (James McAvoy) manifests a disorder that might initially be classified medically as dissociative identity disorder. However, as the film progresses, it becomes clear that something very different is happening, something that cannot be explained by the laws of science or medicine.

In many of Shyamalan’s movies, these seemingly irrational beliefs are often explicitly religious in nature. In The Sixth Sense, social worker Malcolm Crowe (also Willis) finds himself working with a young child named Cole Sear (Haley Joel Osment), who claims to be able to see ghosts. Key scenes play out in a church. Signs is the story of Graham Hess (Mel Gibson), a former Episcopal minister who loses and subsequently finds his faith following the death of his wife (Patricia Kalember).

Unsurprisingly, these early films found some success with religious audiences. Signs was celebrated by religious publications like Christianity Today and Catholic Exchange. In contrast, A.O. Scott criticized the movie’s “fuzzy pop-spiritualism,” and David Edelstein dismissed Shyamalan as “a supernatural blend of huckster and believer.” However, what is interesting about Signs is that it’s the only movie in Shyamalan’s filmography that doesn’t treat these revelations as horrific.

Shyamalan followed Signs with The Village, which often feels like a direct response to the feel-good pop religion of Signs. The Village is the story of a group of people who make a conscious decision to cut themselves off from modernity, to build an isolated rural community in the style of a 19th century settlement. These adults consider modern cities to be “wicked places where wicked people live” and lie to their children to preserve the illusion of a sheltered and protected community.

Michael Atkinson read The Village as “a parable about fearful conservatism.” In hindsight, it feels like a cynical and stinging critique of a particular strand of religious thought, of the “parallel culture” that certain Evangelical communities had built to separate themselves from secular society. Although not explicitly religious, The Village plays as a parable about Evanglicals who had “retreated into fundamentalist enclaves to create a parallel culture through their churches and schools.”

The Village is very skeptical of this community. The elders work so hard to protect their children from outside threats that they are unprepared for the threats that come from within. The movie opens with August Nicholson (Brendan Gleeson) burying his son. Violence develops in the community through a young man named Noah Percy (Adrien Brody), who mutilates animals and eventually stabs his friend Lucius Hunt (Joaquin Phoenix).

“Who do you think will continue this place, this life?” Edward Walker (William Hurt) challenges his fellow elders. He argues for their children. “Do you plan to live forever? It is in them that our future lies.” Walker claims to have protected “innocence,” but the film is bookended by the deaths of two of the children — Daniel Nicholson and Noah Percy. When Walker and the other elders agree to preserve the lie, it is a deeply ambiguous moment. It’s unsettling rather than triumphant.

The idea of a higher power at work is a recurring fixation for Shyamalan. Sometimes, that power is divine in nature, as in The Sixth Sense or Signs. However, it occasionally seems like the planet itself is alive, in a horror movie twist on the Gaia Hypothesis. In The Happening, all the plants on Earth decide to wipe out humanity. In After Earth, the planet itself evolves to be hostile to human life. In Old, the beach seems almost intelligent, luring its prey in and then refusing to let them leave.

Across his career, observers have argued that Shyamalan’s movies reflect an overtly Christian worldview. In particular, The Happening was criticized for being “vaguely creationist” and “Hollywood’s first blockbuster to promote the anti-evolutionary theory of intelligent design.” These arguments would seem to somewhat overstate the case. After all, watching Shyamalan’s movies, one rarely gets the sense that the films are excited by the prospect of a higher power at work beyond human comprehension. They are instead terrified.

Shyamalan’s movies are deeply irrational, which is a frequent (and often deserved) source of criticism of the director’s work. However, there is a consistency to that irrationality. Shyamalan’s movies feel like the work of an agnostic or an atheist who has grown up surrounded by religious beliefs. On a logical and conscious level, those ideas can be rejected or dismissed. Shyamalan has described his movies as “all a little bit like therapy,” and fear is seldom rational.

This central anxiety bubbles to the surface in Knock at the Cabin, a movie in which four true believers attack a same-sex couple at the eponymous cabin. Leonard (David Bautista) is convinced that the world will end if one of three people, Eric (Jonathan Groff), Andrew (Ben Aldridge), or Wen (Kristen Cui), does not die by another’s hand. The tension is compounded when Andrew recognizes one of the devotees as the man who attacked him in a hate crime at a bar years earlier (Rupert Grint).

Leonard’s beliefs are, by any metric, insane. Andrew refuses to accept them. However, Knock at the Cabin repeatedly implies that Eric was — at some earlier point in his life — a believer. In a flashback to the Chinese orphanage where they adopted Wen, Andrew tells Eric that it is okay to pray, if it makes him feel better. There is a sense in which that belief never truly left Eric. It will always be part of him. Something inside of him will always respond to Leonard’s rhetoric, even when it is monstrous.

As with The Village, Knock at the Cabin has a deeply unsettling story hook, resonating with a time when a significant portion of the population have lost any tangible connection to reality, adrift in paranoid delusions and conspiracy theories. Like any good horror filmmaker, Shyamalan taps into a universal and relatable fear. While Leonard insists he did not know ahead of time, it is no coincidence that the victims of this attack are a same-sex couple with an adopted child from another country.

All of this makes sense. It adheres to a certain rationality. However, Shyamalan pushes the idea further, into the deeper and more irrational anxiety that resonates with a former believer like Eric and perhaps to many who grew up internalizing these beliefs. As Knock at the Cabin progresses, it becomes increasingly apparent that there is some substance to Leonard’s argument. For those who don’t believe, Leonard’s beliefs are monstrous if they are wrong, but they are perhaps even more terrifying if they are correct. That’s the real horror.