Early in Jurassic Park, there is a small moment that serves to put the rest of the film in context. Paleontologist Alan Grant (Sam Neill) has volunteered to take a trip to an island theme park operated by eccentric entrepreneur John Hammond (Richard Attenborough). As the helicopter lands, it experiences some turbulence. Hammond instructs the other passengers to put on their seat belts, only for Grant to realize that he doesn’t have both sides of his seat belt.

Grant has two buckles, but no tongue. However, he improvises. He wraps the two buckles around one another, fastening himself as the helicopter lands. It’s a short sequence, but it plays out the movie’s drama in microcosm. After all, the buckle is traditionally described as the “female” side of the seat belt. Grant tying two female ends together to fashion a functioning seat belt foreshadows how “life finds a way” to perpetuate itself on an island composed exclusively of female dinosaurs.

Much has been written about director Steven Spielberg’s fascination with fatherhood, a theme that plays across his filmography from classics like The Sugarland Express to modern films like Bridge of Spies. Interviewers like James Lipton argue that this theme, evident in films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind, may be rooted in the divorce of Spielberg’s parents. Spielberg’s father, Arnold, was absent from the director’s life for an extended period, and they eventually reconnected in the 1990s.

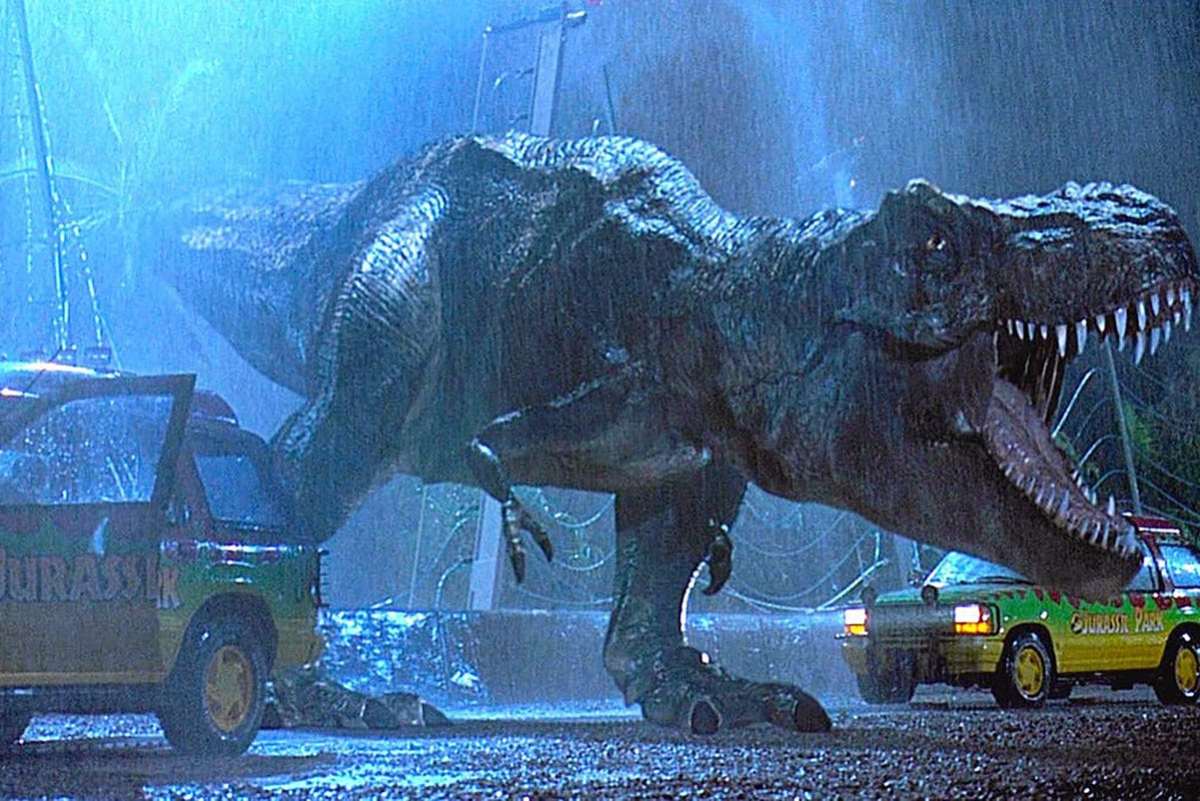

Jurassic Park remains a defining Spielberg film. It is Spielberg’s highest-grossing movie, unadjusted for inflation. Along with the currently dormant Jaws franchise and the fits-and-starts Indiana Jones series, it is one of the rare Spielberg movies to spawn a larger franchise. Indeed, Jurassic Park is the point of origin for one of the highest-grossing franchises in cinema history. It was also one of two movies that Spielberg released in 1993, the year he won his first Best Director Oscar for Schindler’s List.

Fittingly then, Jurassic Park is one of the movies most engaged with Spielberg’s preoccupation with fatherhood. The film is built around the theme, shaping and informing not only the character dynamics, but the plot itself. Jurassic Park is a movie about what it means to be a father. More than that, it is a film about how fatherhood extends beyond the simple biological imperative. After all, the film seems to argue, genetic breakthroughs might render male parents largely irrelevant.

There is an interesting gender dynamic at play in Jurassic Park, one not too dissimilar from that evident in The Thing. Most of the staff and visitors to Hammond’s Isla Nublar theme park are male. This is obvious looking at named characters like Robert Muldoon (Bob Peck), Ray Arnold (Samuel L. Jackson), Dennis Nedry (Wayne Knight), Henry Wu (B.D. Wong), and Donald Gennaro (Martin Ferrero). It is also evident watching the extras in various scenes, from lab technicians to serving staff.

The only women who end up on the island arrive almost by accident. When Hammond invites Grant to visit, looking for his endorsement, he impulsively extends the invitation to Grant’s paleobotanist partner Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern). Lex Murphy (Ariana Richards) ends up on the island with her brother Tim (Joseph Mazzello) because their parents are going through a divorce, and their maternal grandfather Hammond has agreed to host them to give his daughter some space.

Of course, these aren’t the only females on the island. Early on, Hammond reveals that every single dinosaur on the island has been engineered to be female, as a precaution to prevent the creatures from reproducing in the wild. This recalls readings of The Thing that argue that the eponymous extraterrestrial organism might be the only female entity in the movie. As a result, both Jurassic Park and The Thing become stories about what Barbara Creed termed “the monstrous feminine.”

One of the recurring motifs of “the monstrous feminine” is the idea that reproduction is a biological function essentially controlled by women, with both horror and science fiction (and real life) fixated on the terror of men trying to assert control over that biological function. A male scientist trying to create life, with monstrous results, was one of the central themes of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which has been classified as the first science fiction novel. It is also evident in Jurassic Park.

Hammond seeks to control the dinosaurs’ ability to reproduce. “I insist on being here when they’re born,” he tells his guests as they visit the hatchery, allowing him to “imprint” on the infant dinosaurs in the way that their mother normally would. Explaining that all vertebrate embryos are female by default, rendered male by a specific hormone, Wu matter-of-factly states, “We simply deny them that.” Sattler, the only woman in the room, incredulously repeats Wu’s words, “Deny them that?”

Jurassic Park aggressively genders this attempt to assert control of the natural order. “What is so great about discovery?” asks mathematician Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum). “It is a violent, penetrative act that scars what it explores. What you call discovery, I call the rape of the natural world.” Naturally, everybody on the island pays for Hammond’s hubris. Tellingly, the inevitable disaster results from Nedry’s attempts to steal dinosaur embryos to sell them to Hammond’s competitors.

However, there is more to it than this. Jurassic Park suggests that the arrogance of such men trying to assert control of the reproductive process will ultimately render them irrelevant. As Malcolm summarizes the movie’s plot, “God creates dinosaurs; God destroys dinosaurs. God creates man; man destroys God. Man creates dinosaurs.” Sattler completes the thought for him, “Dinosaurs eat man. Woman inherits the earth.”

Malcolm turns out to be correct to call Hammond on his arrogance. While wandering through the park with Lex and Tim, Grant discovers that the dinosaurs have found a way to reproduce. The frog DNA that Hammond used to plug the gaps in the “dino DNA” gave the female dinosaurs the ability to switch genders to insure perpetuation of the species. Despite Hammond’s best efforts, the female dinosaurs have reclaimed their reproductive autonomy. In doing so, they rendered males irrelevant.

These broader themes are mirrored against smaller character arcs for both Hammond and Grant. Both Lex and Tim lack a father figure in their life. Early in the movie, Hammond is distracted by his daughter’s divorce, and the fact that both grandkids end up on the island suggests that they ended up in the custody of their mother rather than their father. The father is never mentioned or discussed, but he seems to hang over Tim’s fixation on Grant as a potential paternal surrogate.

The tension between Grant and Sattler lies in their differing attitudes towards children. Sattler wants children, but Grant does not. The film suggests that Grant may not have a say in the matter, as Malcolm starts flirting with Sattler, asserting that he both loves children and is “always on the lookout for a future ex-Mrs. Malcolm.” Spielberg’s sequel to Jurassic Park, The Lost World, focuses on Malcolm’s girlfriend (Julianne Moore) and another of his daughters (Vanessa Lee Chester).

Over the course of Jurassic Park, Grant learns how to become a father. During a T-Rex attack, Grant is separated from Sattler and Malcolm and winds up traveling through the park with Lex and Tim. Grant finds himself acting as a guardian to the two children, protecting and reassuring them. Repeatedly over the course of the film, Grant cradles the two. When he does so in the helicopter at the end of the film, Sattler looks on approvingly.

Early in the film, before embarking on his journey to Isla Nublar, Grant proposes a seemingly radical theory. He argues that maybe dinosaurs didn’t entirely die out. Maybe they simply evolved and have more in common with modern birds than with reptiles. The film’s closing moments reinforce this idea, with Grant looking out the window of the helicopter as they leave the theme park behind. He notices a flock of birds, suggesting that the dinosaurs are still with us in some way.

This is perhaps the central thematic argument of Jurassic Park, particularly as it relates to Spielberg’s recurring preoccupation with fatherhood. The film was released amid an ongoing debate about the shifting family unit, with same-sex and single-parent households becoming increasingly common. The father was no longer the patriarchal authority figure that he had once been, and there were debates about the role of male parents in this changing social order.

Jurassic Park presents two male responses to this changing social order. Hammond tries to usurp the means of reproduction, to take charge of the means of reproduction. The film argues that this is a folly. In contrast, Grant offers a more evolved and considered take on modern fatherhood, suggesting that being a father is about more than just fertilization and reproduction. Instead, it is an active choice that one makes in the circumstances, not the result of biological happenstance.

As such, Jurassic Park represents an interesting evolution in Spielberg’s understanding of fatherhood.