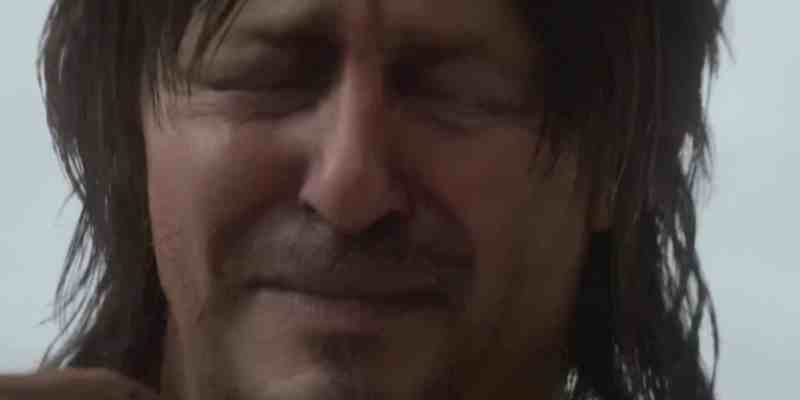

On Aug. 19, Hideo Kojima dropped a weird bombshell on gamers expecting substantive news about Death Stranding during Gamescom’s Opening Night Live. The gameplay infamously teased mechanics allowing you to relieve yourself at virtually any time. You can aim your stream of urine in an arc and shift it from left to right. Your barrage is measured in milliliters, and when you fully empty your bladder, Norman Reedus announces that there’s “nothing left in the tank.”

After the showcase, Kojima further elaborated the following:

- You won’t explicitly see Norman’s junk mid-flow.

- You can’t urinate near people.

- The pee is not only a weapon but a “key.”

- If multiple players shower the same spot, a mushroom will grow in its place and you will get “something good later on.”

At a time when Death Stranding’s core gameplay loop was ill-defined, Kojima painstakingly outlined the mechanics of urination, leaving us to wonder why it mattered and if perhaps he had finally jumped the shark. Such is the contradiction of Kojima as an auteur. He vacillates from sincere to pretentious, self-aware to tone-deaf. It can be difficult to engage with his more mature themes when you have to sift through seemingly juvenile quirks that appear to serve no key function in the gameplay or storytelling.

Kojima previously showed an obsession with bowel movements in the Metal Gear Solid series. Norman’s urination is just the natural evolution of Kojima’s obsession with detail and use of mundane biological functions to uniquely sell the believability of a game’s world.

Kojima’s depictions of bowel movements began as a way to provide comic relief in the frequently self-serious Metal Gear Solid, alleviating tension during dramatic moments. This facet of humor is primarily illustrated through the incompetent and incontinent Johnny Sasaki, a guard whose sole gimmick is his debilitating IBS. He’s first introduced when the soldier Meryl knocks him unconscious and steals his uniform, leaving him sprawled out on the ground half naked with his ass sticking out in the air. From then on, Johnny exists only to be foiled by the player or his own digestive tract.

When the player is captured and thrown into a prison cell, they might initially be distressed. They have no way out and are periodically removed from confinement to be tortured. Things look grim. However, the player character has the opportunity to escape when Johnny, now their prison guard, has to run for the bathroom to avoid soiling himself. From there, you can stage your death by smearing yourself in ketchup or fake your escape by hiding under your bed. When Johnny returns, he’ll run into your cell alarmed, only for you to knock him out again.

Johnny’s incompetence provides levity and empowers the player to feel confident about their abilities. Both Solid Snake and the genome soldiers he fights are the product of genetic experimentation. While the player is depicted as noble and stoic, their rank and file enemies are depicted without dignity. The trope of weak and hapless characters relieving themselves is used again with the anime-obsessed engineer Otacon, who pisses himself when confronted by a cyborg ninja. It all serves to highlight Snake’s bravery in the face of the absurd and make him even more endearing to the player.

Johnny Sasaki in all his half-naked, low-polygon glory.

Metal Gear Solid players can also weaponize and experiment with filth to their delight and benefit. In a somewhat obscure Easter egg in the first game, you can mask the scent of your cardboard box with wolf urine to sneak past a pack in their den. Kojima marries his lowbrow humor with more highbrow concepts to immerse the player in the gameplay and environment.

Through the simple use of the universal truth that everybody poops, Kojima can ground a fantastical setting with familiar details. The majority of Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty takes place on an offshore cleanup facility, a large hexagonal structure that runs the risk of appearing sterile or lifeless. However, the omnipresence of seagulls gives the environment personality. If you’re outside, looking up in an area full of seagulls in first-person may lead to them pooping on your screen. You must also take care to avoid the ground near the hand railings where seagulls lounge, lest you trip on their droppings. If you do, you’re treated to the squeaking sound of your boots on a wet surface before you fall flat on your back, foiled by these annoying pests.

This is one of many tricks the game uses to convince the player they’re in a living, breathing, reactive world. You can catch a guard on his bathroom break, relieving himself over a railing above you and potentially drenching you as you try your best not to attract attention. You can use a directional microphone to listen in on not one but two of Johnny’s bowel misadventures. (Yeah, he’s back.) But the most memorable examples of immersive toilet humor in this title come from the player’s own forays into restrooms — and the shocked reactions of the support team as they watch everything you do.

Every time you’re in the “facilities” you can radio your superiors, who will comment on their invasion of your privacy. Staring at a toilet or standing at a urinal during a call will prompt embarrassment from your commanding officer and girlfriend. Staring at a lewd poster in one of the stalls will elicit jealousy and disapproval. Call from the women’s restroom once and you’ll be mocked. Call a second time and you’ll be branded a pervert.

The myriad of responses you can get encourages you to experiment, testing the limits of the world’s awareness of your actions. The gameplay is not divorced from the story. Break too many taboos and your girlfriend will think you’re a bad person and refuse to save your game. It’s a tribute to the ways in which the game acknowledges creative thinking and consequences, and it’s all completely optional.

Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater continued the legacy of mixing profane subject matter into the thoughtful mechanics of the stealth genre. You can find soiled camouflage in a toilet stall with a stench so powerful it attracts a cloud of flies and overwhelms nearby guards. You can escape a prison cell by feeding your jailer rotten food, giving him some nasty indigestion and leaving you unattended. (He’s a relative of poor Johnny.)

But while bowel movements in MGS3 can be funny, immersive, or awkward, their true innovation is how they can highlight the vulnerability and frailty of its characters. During an interrogation in which Snake is violently beaten by Colonel Volgin, he involuntarily relieves himself. For once, this depiction of human waste isn’t a lighthearted moment, but an illustration of our hero’s defeat. It’s the only video game where I’ve seen the stoic, masculine protagonist wet his own pants during a moment of weakness.

And yet Snake isn’t meant to be a coward, a loser, or a punchline here because the intent isn’t to be juvenile but to use biological function as an extension of emotional storytelling. By subverting his own trope of the incontinent coward, Kojima demonstrates tonal control he’s often purported to lack. While Kojima’s fixation on poo and pee can certainly be childish, he’s not simply vulgar.

Even in the wild tonal extremes of Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots, there’s a clear rhetorical function for the toilet humor. By upgrading Johnny from running gag to supporting character, Kojima uses his legacy of incontinence to speak to larger themes of nostalgia. In a story repeatedly concerned with callbacks to the beginning of the series, it’s fitting that Johnny gets some dimension to his IBS (even if it is very strange). We learn that his condition is exacerbated by pretty girls, and eventually he overcomes it by confessing his love to Snake’s former love interest Meryl, the very woman who made an ass of Johnny in the first game. They wind up getting married.

If we learn anything from Metal Gear going into Death Stranding, it’s that that there can be beauty and purpose in the mundane. This needs to be even more true in Kojima’s version of a walking simulator. You have to be able to use your smaller moments to punctuate the big set pieces. While piss is a small tool in Sam’s arsenal, it contrasts nicely with your bola guns and ghost sensors because it reminds you that Sam is human. His shoes degrade, his body gets worn out, and sometimes he’s gotta take a massive leak.

Kojima’s depictions of digestion reflect an iconoclastic attention to detail. He isn’t afraid to risk ridicule in his expression of natural human experiences. In that light, there’s nothing weird about Death Stranding’s piss mechanics. They allow for a greater range of expression than is typical in a AAA title. At last, there’s a game that truly captures what it means to be alive and free. What a relief.