With morality systems, DNA-spliced animals, and chili-filled pizzas promised at launch, Let’s Build a Zoo has set itself up as much more than a standard zoo builder. However, even with a PC release set to arrive before the year is out, there’s plenty of work left to do. We sat down for a chat with the founder of developer Springloaded, James Barnard, to find out exactly what makes Let’s Build a Zoo stand apart not only from other zoo-building games but other games in general.

The Escapist: Tell us about who you are and where the idea for Let’s Build a Zoo came from.

James Barnard: I’m the founder of Springloaded. I used to work in AAA… I worked on things like Star Wars: The Force Unleashed. Corporate life had really driven me into the ground, so I left that and went on holiday for a bit, which was my experiment in trying to build indie games. I assumed it was just going to be eight weeks or something until I had to get another job, but it’s been eight years. Somehow, I’ve managed to survive all that time.

I was a lead designer at Lucasarts, and before that, I was a producer, and then before that, I was an artist and a musician for all that time as well. I had done a little bit of programming, but then when I left LucasArts, I guess I became a full-time programmer. Now, I’m more a programmer than anything else. I made a bunch of games on my own, and then I employed some folks, and we actually became like a real company. I’m based in Singapore. I moved here – I’m from the UK, originally – because I went to some career fair and LucasArts was there, and they said, “You seem like the kind of guy we want. You should get a job in America!” And I explained to them that I have no degree, and I’m far too “un-green-card-able.” So, they said, “You should go to Singapore then! It’s easier!” Which, it’s not anymore, but it was back then. So, yeah, I didn’t really expect to have to move to Asia. It wasn’t really ever a plan, but here I am, nonetheless.

When I was a kid, I played Theme Park and loved it. As I got older, I kept checking in with the genre, and I just really didn’t like it anymore. I remember being really excited about Cities: Skylines and trying to play it, but the interface and the way it felt… I just couldn’t get into it. It was complicated and slow, and it lacked any humor. It was just so dry, and I kind of thought back to how ridiculous games used to be in that genre. (Then) I went back and I played Theme Park again as I started thinking more about it, and when I played it, it was even harder to play than Cities: Skylines! Just as a kid, I guess I was more determined to punch through and play that thing.

So, we really kind of focused in on … not making the game feel like a job. We have this really interesting kind of difference (as a team) where I’m really into sick jokes and things being really dark and evil. Then we have two girls that draw most of the art, two local Singaporeans. They get dark stuff, but they also love cute stuff. So there’s always this little bit of conflict between us, and it brings out these really great things where stuff goes super, super cute and super happy and joyful, and then I’m always trying to underpin it in some level of darkness. … So it made total sense to do this morality system where it can go either way. If you want to be the most evil, horrific, messed up player in the universe, you can be, or the nicest player and make your zoo nirvana, you can be. That’s kind of the genesis of the game.

Can you describe the core gameplay loop of Let’s Build a Zoo?

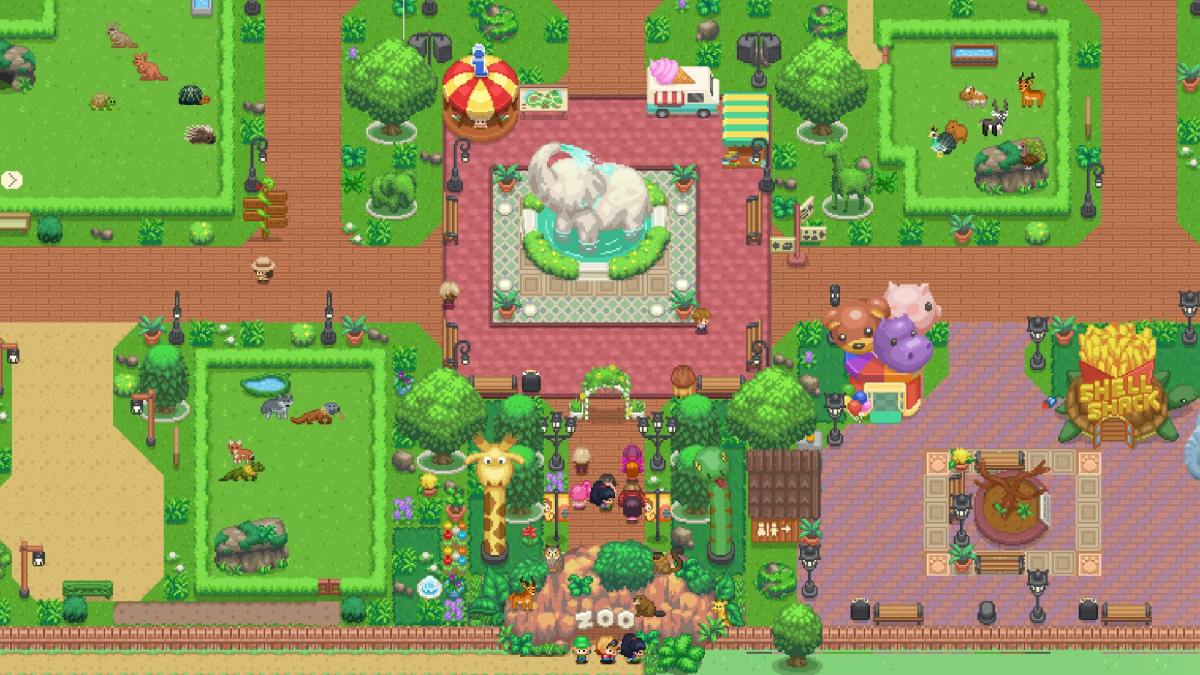

James Barnard: The fascinating thing about the game is that we’ve got millions and millions of ideas that all easily slot into the core gameplay loop. … If the game does well, we’re going to carry on working on it for years to come. We’ll make it massive. So, to describe the gameplay loop, currently there’s a sort of world map, and at the very beginning of the game, you have one zoo that you can build. Depending on how well you do with that, you earn money to unlock other places in the world map. Currently, there’s only one other place, but we will add more and more places as we continue to develop the game. After launch, we’ll be building more islands and locations and things.

Once you start your zoo, you get a loan and a small plot of land. You can go to the other zoos on the world map and trade with them, and you essentially get animals from the world map; you breed them in as many ways as possible to collect all the different variants. As you get more animals and rarer animals, more people come to the zoo, and it’s up to you whether or not you decide to screw them over by ripping them off, or whether or not you decide to be nice to them and make them have a lovely experience, but you can make money in both directions. Right now it’s probably slightly easier to be evil in the game and make more money, but that’s kind of like real life, isn’t it? In the long term, it probably balances out. There’s a lot of payoff if you go the good route toward the end of the game – not that there really is an end.

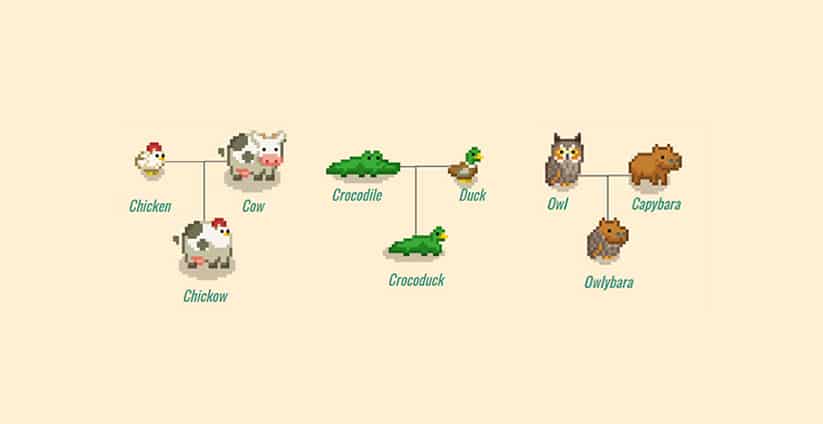

You continue to build more and more popularity with your zoo, and once you’ve bred all types of animals, you’ll have mapped its genome. Once you’ve mapped an animal’s genome, you can start crossbreeding it with other animals, which is obviously one of the most delightful things in the game. We have an insane volume of crossbreeds, so we don’t expect anyone to ever even breed all of the animals.

Morality takes you down different paths. I can start making “evil” choices. For example, the hot dogs, you can put prime meat in them, or you can just put tails and eyeballs in them. If you set the ingredients to be really, really terrible, people will happily buy, but they may start throwing up. You’ll make more money, so it’s OK, but your morality will go down. There’s also a research grid, and some of those things, you can’t use unless you’re evil enough. The same thing goes for the “good” path. If you decide to go good, you can unlock things like farming, and you can unlock energy generators like wind turbines and stuff like that because you’re going to have to start paying your utility bills. You can actually start giving back electricity to the grid. So, there’s a whole kind of ecological objective there.

In the end, the objective, if you go good, is to become completely self-sufficient and not have to buy anything from anyone and not put carbon dioxide into the air. You can even feed your animals without killing anything, by growing lab meat and stuff like that. But if you go evil, then you can’t actually use things like wind turbines, so you have to commit to the destruction of the planet, pretty much. You can just build giant factory zones. In fact, one of the things I really love about the game is that, if you want to, you don’t really have to play a zoo game. (laughs) You can just make a farming game, or you can play a factory game if you want to. It’s up to you how you do it.

Interestingly, we’re trying to make sure that, in the game, you can swing easily from good to bad if you want to. In the space of 30 game days you can just say, “I’m going to be bad now,” and then you can just give up all your good stuff and become terrible.

A lot of games tend to trap and lock you into a set path once you’re heading in that direction, so I love that there’s that freedom to switch if you want to.

James Barnard: It just feels so disrespectful of your time, you know? (In some games) you play through this long story, and you make a few choices, and really it all comes down to some big ending (cutscene). And then what? You’re supposed to go back and play the whole 40-hour game again to see the different ending? I‘ve always found that really horrible. And in this day and age, what does it result in? Everyone just goes and watches it on YouTube. No one’s actually going to play it twice, right? Unless you love it.

I was influenced by Forager. I love the way Forager is just this giant, massive thing that you kind of explore and build and mess around in. I kind of always wanted to make something like that, where you have this huge sandbox in which you just do what you want, and you’re not locked by your choices. I didn’t want people to have to pause the game and quit and start again.

How important is the story in Let’s Build a Zoo? Is the narrative going to be really deep? Or is there even a story at all?

James Barnard: I really enjoy writing little narratives and little characters, not sprawling epics. But I like to give interesting perspectives on characters. Most of the time, it’s just silly things, like comedy. We have little jabs at people like Jeff Bezos in the game and things like that, but it’s not supposed to be political. We make fun of things in all different directions. I would hate it to come across as political or preachy. There is an intended narrative, but it’s not supposed to be heavy; it’s very light. The focus of the game is building stuff, and from knowing how people play games, I imagine 50% of the people won’t read a single word I wrote. (laughs) … And that’s cool! I don’t want to stop people from playing it the way they want to play it.

DNA splicing is one of Let’s Build a Zoo’s key features. What are some of the other ways that the team will keep the game interesting throughout each player’s experience?

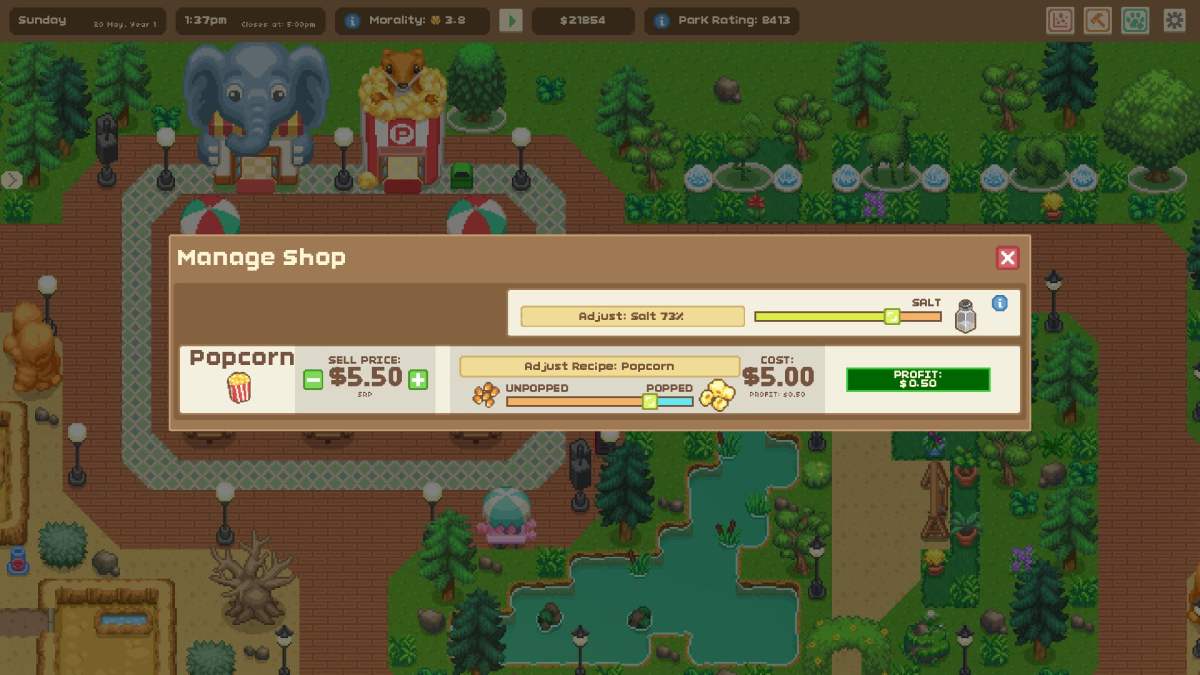

James Barnard: Well, obviously there’s the depth of all the different shops and the systems and the food that you have, and you can adjust those recipes. But the interesting thing is also how you source the food for those shops. In the beta, the shops just auto-restocked, and they still do auto-restock, but you can supply them by doing underhanded things or by having your farm and stuff like that.

There are also things that can happen in the game to impact the way you manage your zoo. Certain events will happen, and you’ll have choices to make that will impact base modifiers on certain things happening in your zoo. So, hopefully, those things will be surprises, and you’ll be entertained. As for how it changes, the sheer scope of it is the thing that’s so different, I think, when compared to a lot of games — it’s just massive.

How far can we push those mechanics like DNA splicing? Are there any crazy combinations you can think of as particularly fun examples?

James Barnard: The artists have to go through all 300,000 animals. I wrote some code, and we slice the heads off and their bodies and then align them, roughly, in code. And then the artists went through all 300,000 and realigned them because they wanted them to look perfect, which is mental. I mean, that’s months of work. So, there were so many times where there would be a surprise, and they would post a picture in WhatsApp. Like, a snake plus a rhino just looks really hilarious. Some things we’d just laugh our asses off at it because it’s so good. If you merge a chicken with anything, it looks fantastic. Putting flamingo bodies on things is just really silly.

The delight comes when we say, “Imagine what’s going to happen when we add more animals? Imagine how more ridiculous it’s going to get?” I wish I could talk about all the plans we have, but that would suck because then if we don’t do them that would be awful. But the stuff we have planned for the future of the game has got all of us really excited. We want to do more stuff in the sky. We have the helicopters flying in, and we have a couple of other things flying around. That’s a whole area that we want to explore more and do stuff up there so it becomes more of a vertical game as well.

Let’s Build a Zoo sounds like it’s evolving in so many ways. Is there discussion among developers about how we can do more with the zoos? How can we interact with guests, and what are some more of those ideas you might have?

James Barnard: I guess they’re mostly passive, right? You observe what they do and then try to react to it. There are people who turn up to your zoo who are VIPs, and they do certain things like inspect the animal welfare, or they’re streamers or food reviewers. Those people you can interact with and bribe or do other things to, to make them try to improve your business. Customers generally act as a thing for you to respond to. They’re like an announcement system for what you’re doing wrong. Each person who comes to the zoo has a different set of desires and a different set of tolerances. Chili, for example. You could stuff a bunch of chili onto a pizza. I think there’s around a one-in-five chance of the person loving chili, so it’s not a guaranteed response that they’ll all be like, “Oh, god,” and then run around and need to buy a drink.

Each customer comes from a different place, like a different city. There are, like, five towns that they live in. And as you open up bus routes, they come from different towns, and people from different towns have different wealth. There’s a lot of subtlety going on.

Will Let’s Build a Zoo have a definitive ending where we see the credits roll? Or can we build on our zoos indefinitely?

James Barnard: You can build on your zoo indefinitely – 100 percent. Are there endings? There will be endings, for sure. Most definitely some ending moments. It will be like a lot of other games; when they end, you can carry on again after. Part of the point, in the game, is you can always go to one of your different zoos, and your previous zoo will still exist. So, if you unlock the second map, the first map still exists. It still sits there, so you can always go back and tinker with it. That’s something, long-term, we want to expand upon as well. (We want to make it so that) the zoos can work together when you build and things like that. It probably won’t work at launch, but it’s one of those things where you’re like, “I want to build a zoo empire and have them all interact!”

Springloaded has been transparent when it comes to how it’s changing Let’s Build a Zoo. How has fan feedback to the beta and the demo impacted development in the long term?

James Barnard: I think it’s multifaceted. The surprising thing is that people have been so positive. In some ways, it’s made it harder to find out what’s wrong, but it’s also made us really stressed. We’re used to people not caring about our games, so knowing that people actually care about one for once is like, “Oh no! We’ve got all this extra stress! We’ve got to make everyone happy! We don’t want to let people down!”

That’s probably why we’re taking a lot of things out of the game that we don’t think are perfect. Let me give you an example: When the beta launched, I just sat there watching Twitch for five days, just watching people play the game. Really fascinating, and it did change the game substantially. I think we were, at the time, trying to really focus on very deep systems and the evolutionary gameplay, where things would just sort of happen.

(But) I think the more we watched people play it, the more they weren’t necessarily connecting with the deeper things inside the game, and they were just having fun. They felt like what I felt when I was 15 or whatever, just playing a game and having fun, not caring. That did influence us back to taking out anything that wasn’t fun.

We had this system that was really complicated. Every animal eats different food, and all the food costs different amounts, and you use these sliders to get it the perfect nutrition — that’s still in the game. On top of that, there was a layer where you had to run the storeroom, and in the storeroom, you have to keep an eye on every single type of stock, every single type of thing that you want to buy, and every single thing that you want to buy has a different delivery day because it comes from a different place in the world. And then it all has a different shelf life. So, to manage all that stuff was really hard. … In the end, even though I really like it, we just took half of it out.

So, (beta feedback) definitely was an influence on us. Putting the fun front and center.

What platforms can we expect at launch?

James Barnard: As far as I know, our launch is on Steam and the Epic Games Store. Then, beyond that, the official line is, “We’re coming to everything.” I have all the dev kits in my house, so that’s a sign of what’s coming.

In the beginning, when we started building the game, we were 100% focusing on complete cross-platform. So, we made everything controller-friendly. As we closed in on launch for PC, I think we started really focusing on the PC as a platform and its strengths with things like mouseover. I think the user interface will change quite a bit (on consoles). There are things I’d love to say I want to put in console versions, but I think the publisher would tell me off. (laughs) I really love the direct control and things like that, but it will certainly not be stripped down from the PC version. That’s definitely the case.

Is there anything else you’d like to add about Let’s Build a Zoo, Springloaded, zoo-building games, or indie game development in general?

James Barnard: I think the big takeaway is that the game, at launch, is going to be a fun, not-feeling-like-work kind of game. In the beginning, it’s going to be a certain size of game, and it’s going to, hopefully, be what everyone wants. But I think over the years, we can turn this into something that just becomes so massive. That’s the hope, right? If we get some decent sales at launch, we don’t have any specific desire to stop working on it. I hope that works for people – building a community around a game. We want the game to morph over the years and become something almost unrecognizable from what it is today. I always find that really exciting when games do that.

Maybe in another six months, we’ll have another conversation, and I’ll tell you about something incredible. I think that the things we’ll do to the game in the future will really surprise people.

Let’s Build a Zoo is coming to PC via Steam and the Epic Games Store sometime later this year. Console versions are expected to arrive sometime next year.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.