Horror games are a popular genre for new game developers. Jump scares and loud, startling music provoke a primal response in most people, allowing even the most basic projects to have a profound impact on the player. The remaining Flash sites are crammed full of games like this, wringing out a player’s startle reflex while offering little in the way of actual gameplay. At first glance Lucid Dream appears to be one such project, sporting a basic interface and standard horror tropes. As the (free) game progresses, however, a more sophisticated approach to frightening the player becomes apparent. Carefully paced creepy occurrences and thoughtful puzzle design create a tense, uneasy experience that is far more frightening than any shock-based slideshow.

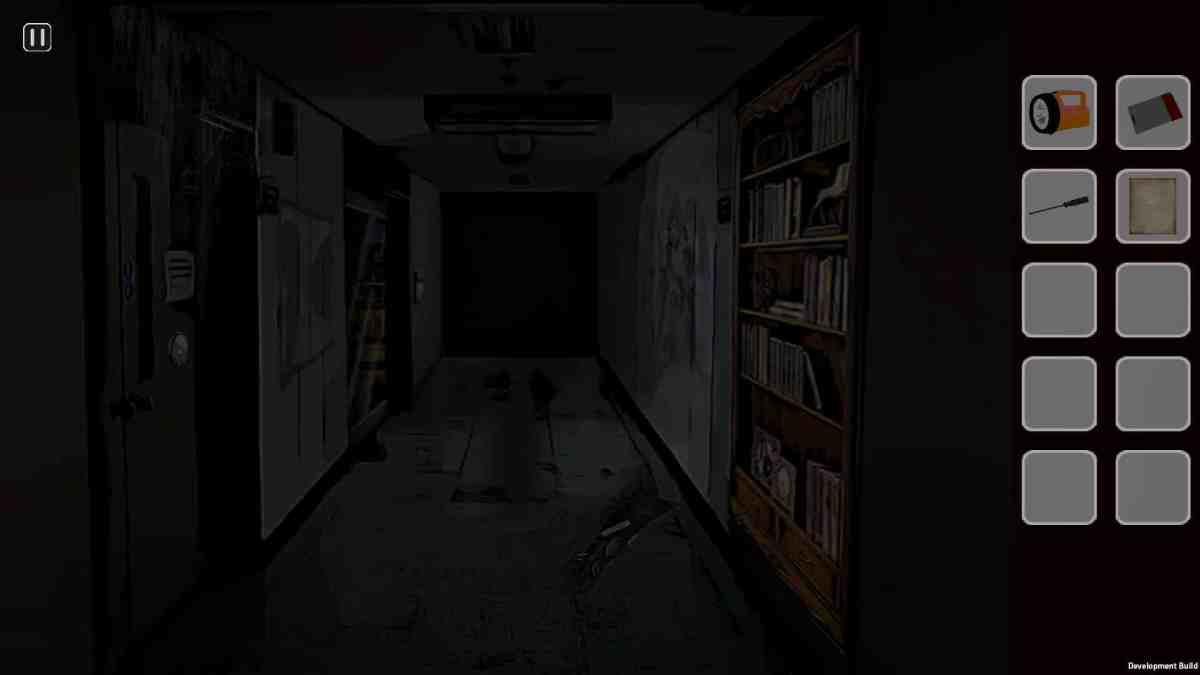

It was a night like any other. Ann had gone to bed as usual, arms wrapped around her favorite toy rabbit, but when she woke up the world around her had changed. Her cosy bedroom has been replaced with a bland, utilitarian hotel room. Peeking out the doorway, she sees an unfamiliar stairwell twisting away at strange angles. Unable to wish herself awake, she wanders further into the unfamiliar territory, searching for a way out of the increasingly unpleasant dream. She has to be careful, as she can feel something watching her. Footsteps echo down the corridor, and doors unlatch when Ann’s back is turned. Gripping her torch ever tighter, she marches forward into the dark.

Lucid Dream mostly plays as a straightforward point-and-click adventure game, collecting items and using them in the correct place to progress. Interactable objects are easy to spot, highlighted with a thick white outline. Each item has a purpose and is discarded when no longer useful, avoiding the junk-filled inventories common to the genre. The dream setting could have made for a good excuse for all sorts of illogical puzzles, but most interactions make sense, such as placing a missing book into a shelf to open a doorway or collecting an eyeball to get past an iris scanner. Most interesting are the sections involving the bathroom mirror, which can be stepped through to explore a dark, inverted version of the world. Later puzzles require a fair bit of jumping back and forth between worlds, setting up half of a device in one room and finishing it off in the mirrored version.

Along with this head-scratching, however, Ann needs to keep an eye on her surroundings. A malevolent presence is stalking the halls, and if it catches her, all will be lost. A creaky cupboard in the middle of the hallway is the solitary hiding spot, central to the various explorable areas but frighteningly far away when Ann is being chased. The monster is fairly forgiving, however: I zig-zagged towards the hiding spot in a terribly inefficient manner due to panicked clicking and still made it to safety in time. Nonetheless, the knowledge of being stalked gives greater urgency to every action, a dire need to find where a handle fits or code is written down.

Just when Lucid Dream seems complete, the player is transported to a new area, a more traditional maze complete with mini-map and masses of hiding spots. The creature loses the restraint shown in the earlier area, chasing down the player at alarming speed. Ann’s path to finally waking up lies at the end of the maze, but getting there is grueling, a constant case of slowly moving from one point of cover to the next. The section is technically well done, with a strong sense of danger, but it feels like it belongs in a different game. Rather than slow, cautious puzzling of the earlier area, the maze is designed more like a stealth game, relying on reflexes over logical abilities to progress.

Lucid Dream does have a loose story, found in notes and newspaper clippings scattered around the building. The malevolent presence has good reason for being so angry, as it was the victim of a terrible crime committed many years ago. Some elements of the story lose impact due to rough spots in the translation though; the English is all legible, but newspaper articles are written in a very child-like voice, and other segments have distractingly odd word choices.

This weakness in the written word is made up for in brilliant visual storytelling, the twisted world and perfectly-timed scares creating a tense atmosphere. The game is made up of fairly simple images, but the surroundings change just as soon as the player gets comfortable. Grabbing a fuse for a puzzle plunges the world into darkness, Ann’s torch barely emitting light at all. The mirror world is all deep blacks and scratchy white lines, bloody handprints the only source of color. The game’s small world is seen from many different perspectives, keeping the player off-balance.

With just a smattering of jump scares and a whole load of atmosphere, Lucid Dream is indeed a vivid vision of horror. While the end section did not quite match the rest of the game and some of the writing was a bit rough, the wonderfully balanced puzzling and creeping horror make the game an intense experience from start to finish.

Next week we will be playing Helltaker, a modern take on the box-pushing puzzle. The game can be downloaded from Steam. If you would like to share your thoughts on the game, discussions will be happening in the Discord server.