In today’s canon of universally recognizable characters, few are as reliably anodyne as Mario. Those who grew up with him – perhaps a majority of gamers under age 45 – would likely describe him in the same way: He’s a plumber with a mustache who heroically saves Princess Toadstool. That there are so few new takes and reinterpretations of the character is remarkable even by the standards of corporate mascots. After all, Mickey Mouse (maybe Mario’s closest peer) is frequently reimagined for new eras, with Paul Rudish’s fascinating and subversive version being the most recent example.

That stability runs counter to the period of relative upheaval in which Mario was created, and the original man he was meant to be. Shigeru Miyamato designed Mario as a foil for Donkey Kong, describing him as neither “handsome nor heroic” but an “everyman who rises to heroism in the face of adversity.” He was not built with good nor evil in mind, and was not meant to be noble or moral. He was just a worker who played the hand he was dealt.

This is plain in the very earliest works in which Mario is featured. In Donkey Kong, he faces a troubled ape who has stolen his girlfriend. But in Donkey Kong Jr., Mario has captured his nemesis and become the antagonist for Kong’s young son. There are no heroes or villains in these stories, only decent hominids in bad situations. Mario’s everyman credentials were built via traits like his collection of working-class jobs (like a construction worker in Wrecking Crew), and his predilection for pinball. Mario was one of us, not someone to look up to.

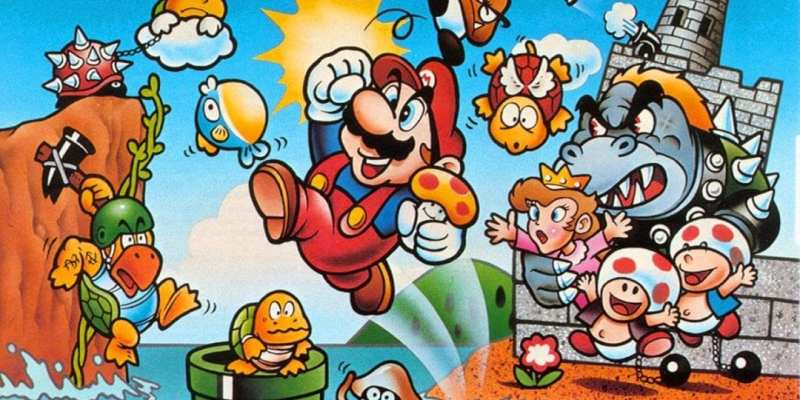

Super Mario Bros. rewired the Mario story, pitting him directly against the black magic of the Koopa and making him the sole savior of the Mushroom Kingdom. This version of Mario became his most commercially successful portrayal and turned him into an icon, and so it stuck. The shades of gray that previously defined his actions receded into a depiction of pure goodness of heroism. Mario’s occupational pursuits, which had coalesced into a career in plumbing, also faded from view.

For the better part of 30 years, Nintendo’s main Mario games focused on the noble Mario and his face became synonymous with gaming. Given his popularity, it’s surprising how little additional characterization Mario received beyond his fondness for saving princesses. He said basically nothing from 1985’s Super Mario Bros. until Super Mario 3D World in 2013. He owned nothing, and had no visible home. He doesn’t reply in conversation, and barely reacts to events, even when he is tried and imprisoned for crimes he did not commit in Super Mario Sunshine. This emptiness is thrown into even starker relief when compared to the litany of information we have on Bowser, such as that he lies to his son, is anxious about the strength of his kingdom, and loves very specific car colors and models. The most we learn about Mario from his direct action in these games is that he enjoys lobster and probably doesn’t get kissed very often.

Side stories like the Mario & Luigi games give us a perfunctory look into Mario’s home and life in the Mushroom Kingdom. But they also play his empty-vessel stoicism and silence for laughs, acknowledging in some ways the hollowness of this form of the character. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Luigi himself, who is richly portrayed as insecure and jealous of his empty-headed, princess-recovering meat slab of a brother. Almost anything we learn about Mario we have to learn from the way others react to him, even if it’s just how they say his name.

Decades of unexamined, reactionary heroism came to a head when the Wii U, a console headlined by the superbly designed, nearly story-free Super Mario 3D World, flopped quickly and spectacularly. This in turn forced Nintendo to rethink everything, including the depiction of their most famous hero.

The Mario of Super Mario Odyssey is different, which caused some hand-wringing from his longtime fans. The amorality of his newest ability – taking over the bodies of his enemies to break their wills and control them directly – was shocking because it was a hard break from how Mario had been portrayed for years. But it was also not different from the Mario of the Donkey Kong games, who would use any tool to get through the situation in front of him.

Players also learn a great deal more about Mario through his direct actions in Odyssey. Early on, he rejects the top hat form of his new, sentient cap pal in a nod to the proletariat roots of Wrecking Crew. He takes on a mobile home, an airship, which he fills with mementos of his journeys. And, in the hardest break from the past, he pursues Princess Peach not just heroically but romantically and is rejected for being overly aggressive.

That’s an ignoble end for a previously perfect hero, but it’s familiar territory for Mario, a man who wasn’t initially built for great things. His early explorations, as amoral and itinerant as they were, built the foundations of a gaming era in which he, and Nintendo, called the shots. Perhaps a fallen Nintendo needs a fallen Mario before they both can ascend again.