PlayStation Vita and I found each other at a vulnerable moment. There we were: at the beginning of 2012, afraid to love again. I’d been hurt before. Nintendo 3DS’ disastrous first year, and half a decade of infrequent, lackluster PSP games made me leery of yet another stab at high-end portable gaming. Vita, an oblong chimera of trendy tech features, needed someone to believe it could deliver something beyond half-step versions of big budget PlayStation games like Uncharted. We met on release day at a Walmart in Colorado, awkwardly getting to know each other over some Hot Shots Golf. By the time I played Mutant Blobs Attack a week later, we were in love.

Now I have to say goodbye to the Vita. Cue the Boyz 2 Men. Sony is ending production of the little portable that couldn’t. Sony itself hasn’t said the dream is dead, but Koji Igarashi’s announcement that the Vita version of Bloodstained was cancelled because the platform is being discontinued, coupled with the announcement that cartridge manufacturing will stop in 2019, is a clear sign that the end is nigh. As Vita fades even further into obscurity, though, it’s remarkable how my first experiences with it signified its greatest strengths.

The world expected Vita to succeed on the same playing field as its predecessor and Sony’s home consoles, as a showcase for technologically advanced video games with Hollywood gloss. It was supposed to be a breeding ground for new Uncharteds untethered from televisions – grand realization of the second-screen market that entertainment businesses were trying to cultivate at the beginning of the ’00s. Instead it became a fertile ecosystem for undomesticated experiments like the aforementioned Mutant Blobs. As with storied hardware failures like Dreamcast and Gamecube, PS Vita was a paradise for beautiful, unusual games seemingly custom built for the people who sought them out with the greatest fervor.

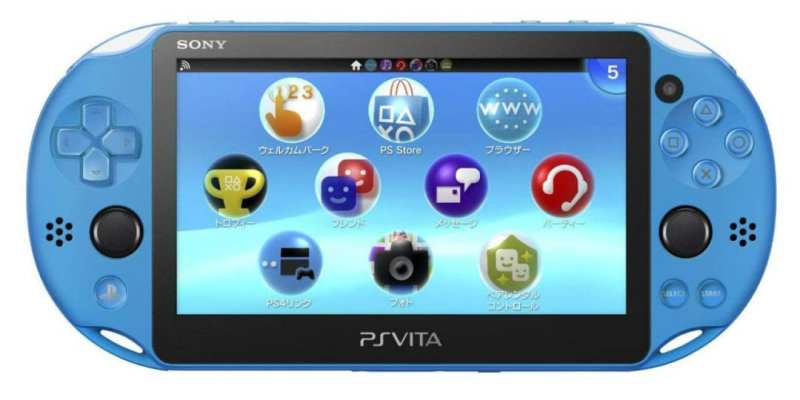

This was in spite of the hardware itself. As a machine, Vita reeks of classic Sony hubris. Even now at the end of its life, every last feature of Sony’s least-favorite child feels like a labored mix of Cool Dad posturing and corporate skullduggery. “Every other piece of tech has a multi-touch screen in the ’10s? Well ours has a touchscreen on the back! And, like, all the cameras all over” for alternate reality games and taking pictures that don’t look as good as the ones on your phone. “See this OLED screen? It’s got the inkiest blacks, kids. All this hotness comes in at just $250 too.” Of course it uses a proprietary memory format in an era when we’ll rely on digital distribution to sell the bulk of our games, and in a decade when SD cards are finally cheap. How else will people know it’s a luxurious style piece unless it’s monumentally expensive for no reason? This is the kind of industrial design decision-making that nearly sank the company in the ’00s as it was desperate to keep its stranglehold on both consumer electronics and lucrative format licensing like the compact disc, which it co-owned with Panasonic.

Those corporate goals also sank the Vita. The handheld never became the sales driver the PSP was for Sony – the company sold over 80 million of those compared to roughly 15 million Vitas – nor did it become the second home for tentpole blockbuster games like Killzone that it was supposed to provide with its beefy graphics processor. Of the more than 1,400 games playable on Vita, Sony itself only published a few dozen. The bulk of them were ports or re-releases of other developers’ games like Borderlands 2 and The Walking Dead, and the company stopped making Vita games itself in 2015. While Sony’s vision for the Vita shriveled up after just a few years, the system found its true calling with small but no less ambitious games and the sort of bizarre B-list work developers churned out en masse in the good old days of the PS1. It never wanted for variety. While few games were exclusive to the platform, many games found their true home there.

This was the magic of being a Vita owner. Almost every week over the past six years, something interesting would show up on the PlayStation Store. A tide of the most celebrated independently developed games ended up on the machine. Spelunky‘s endless well of cruel platforming challenges, Fez‘s maddening leaps of logic, the endless crunch of failed runs in OlliOlli — small studios flocked to Vita. Vita owners bought a lot of games. “Honestly, Vita owners are the ****ing best,” Chris McQuinn of Drinkbox Studios, the developer of Mutant Blobs Attack, Guacamelee, and Severed said in a 2014 interview. “People rag on the Vita so much, and I think people who rag on the Vita don’t understand, at least from a business perspective, the purchasing power of Vita owners. Vita owners are serious purchasers of games. It’s an amazing system.”

This was the magic of being a Vita owner. Almost every week over the past six years, something interesting would show up on the PlayStation Store. A tide of the most celebrated independently developed games ended up on the machine. Spelunky‘s endless well of cruel platforming challenges, Fez‘s maddening leaps of logic, the endless crunch of failed runs in OlliOlli — small studios flocked to Vita. Vita owners bought a lot of games. “Honestly, Vita owners are the ****ing best,” Chris McQuinn of Drinkbox Studios, the developer of Mutant Blobs Attack, Guacamelee, and Severed said in a 2014 interview. “People rag on the Vita so much, and I think people who rag on the Vita don’t understand, at least from a business perspective, the purchasing power of Vita owners. Vita owners are serious purchasers of games. It’s an amazing system.”

It wasn’t just indies, though. Japanese developers specializing in visual novels, RPGs, and offbeat action games vanished from the traditional games market at the end of the ’00s. Staples of the 1990s, those genres proved to be prohibitively expensive to make on the PS3 and Xbox 360. On Vita, though, games like Virtue’s Last Reward, Dragon’s Crown, and the Ys series found the perfect ecological balance between audience and market sustainability. Vita also became one of the richest archival platforms available, with hundreds of PS1 and PSP games readily available alongside stellar remasters of out of print classics. Nowhere else could you (legally) play Final Fantasy 7, the original Resident Evil trilogy, and Grim Fandango all for less than $100 bucks.

In fairness to its detractors, Vita has always lacked icons. In 2018, its only remaining exclusives are wild experiments that use its unique hardware features like Ovosonico’s Murasaki Baby and a veritable ocean of softcore Japanese smut like Drive Girls. No game lovers desperate for the authentic experience are going to hunt down Vitas for a long lost Metal Gear game like they do with GameCube or a beloved developer’s deep cuts like Sega’s Cosmic Smash on Dreamcast. The Vita has never needed the biggest names to shine, though. Part of its appeal is its hidden quality: that a vast reservoir of games was waiting to be found beneath the crusted remains of what was supposed to be a PS3 you could take anywhere.

Now it’s time for Vita to be buried. I’ll toast the little oval over the next year as the flow of indies and physical releases from places like Limited Run Games reduces to a trickle before finally drying up. Chances are I’ll keep collecting for it as well, picking up oddities like Yomawari before they become crazy expensive collectibles, as always happens with flopped gaming machines. (Just look at the prices for Sega Saturn games on the used market.) The truth is that the Vita doesn’t truly need to be mourned. Its legacy of variety, portability and preservation are wholly intact on Nintendo’s Switch, a device that has all of the hardware strengths of Vita, none of the weaknesses, and can still function as a home console to boot. I’ll still miss it, though. Here’s to you my weird little love, last of the true portables.