There hasn’t been a truly tectonic shift in how we play games since the 1980s, when Nintendo finished the job Atari started of moving games from arcades to living rooms. Since then, it’s been baby steps with the occasional short hop. The ’90s brought better graphics, more convincing physics simulations, and an extra dimension. In the 2000s, the rise of massively multiplayer online games and the ascendance of Steam as a distribution platform began to gently shake up how we play games and who could make them. Without another 1980s-style paradigm shift, you might expect that the games industry of the 2010s more or less resembled the industry of the 2000s and the ’90s. But looking back on it now that it’s over, it didn’t, not even remotely. The 2010s were when the sum of all those gradual changes finally resulted in the industry being transformed, like the Ship of Theseus, into a completely different beast.

In the 2010s developers didn’t just continue building on the previous decades’ foundations; they completely reimagined what games were capable of. If the 2000s brought online multiplayer to the mainstream, then the 2010s blurred the line between single player and multiplayer altogether. Games like Death Stranding allowed players to aid one another without ever directly interacting, and No Man’s Sky dropped players into the same universe but across insurmountable distances. In the 2000s it was possible for smaller games from auteur creators, like Ico and Katamari Damacy, to become respectable successes. But in the 2010s, downright microscopic titles made by just one or two people often exploded into the cultural mainstream. In the 2000s mobile gaming was ascendant as a viable new platform. In the 2010s Pokémon GO blended mobile gaming with real-life adventuring, and the hot new platform of the decade was bona fide sci-fi-made-real virtual reality. The games of the 2010s were defined less by the kind of incremental, linear advances typical of previous decades and more by inventive lateral moves into once-unimaginable territory.

This is not a list of the best games of the decade. This is a list of my favorite games of the decade, why I liked them, and what I think they say about the industry and culture that produced them. Some of the games on this list defined the broader cultural trends of the 2010s; others willingly defied them. Some of them artfully broke down previously sacrosanct boundaries, and some of them just did classic video game shit really, really well. All they truly have in common is that for technological, economic, or cultural reasons, or some combination of all three, none of them could have been made in any other decade but the 2010s.

10: The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015)

Systems-driven design and partial automation were behind a lot of hot games of the 2010s. Indie and AAA developers alike leaned on procedural generation to create worlds that were different every time you visited them, as in Enter the Gungeon. Immersive sims came back, with games like Dishonored using interacting systems to spontaneously generate encounters rather than designing them directly. And titles like Fallout 4 used dynamic quests to serve up a theoretically infinite amount of content. But right in the middle of the decade, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt became an instant all-time classic by rejecting these trends. The Witcher 3 demonstrates that even the most sophisticated content-producing algorithm is no substitute for rolling up your sleeves and doing shitloads of hard work by hand.

What stood out most about The Witcher 3 on release was how much of it there was. Not just in the breadth of its handcrafted open world, but in the depth of its dozens of quests, subplots, and vignettes. There are no “go into the woods and kill five rats” filler quests in The Witcher 3. Even the simplest monster-hunting contracts take the form of interactive one-act plays, with their own unique casts and settings, and often with multiple potential endings. Characters obscure the truth to advance their own agendas, lifelong bonds are broken, sleepy villages’ shameful secrets are dragged into public and resolved with force — there’s more human drama in The Witcher 3‘s side quests than in many major releases’ critical paths. Andrzej Sapkowski’s Witcher books are half epic novel cycle and half short story collections, and CD Projekt Red honored this twin legacy by giving equal attention to its kings-and-witches main plot and its serfs-and-beggars side content.

9: Sonic Mania (2017)

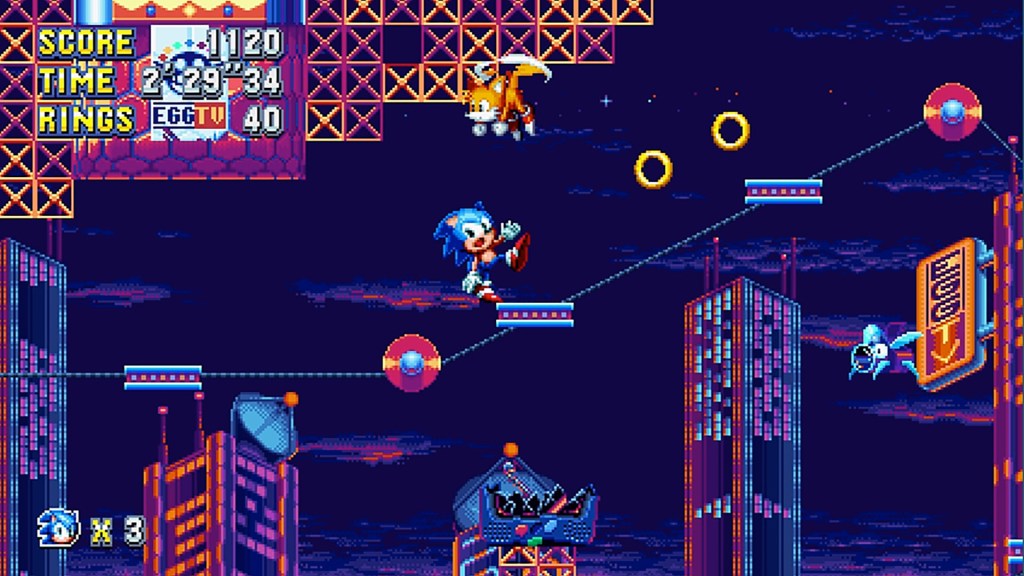

Fan games are as old as games themselves, and the Sonic fan game community has always been especially rich. Intrepid creators have taken cracks at remastering the classics, with projects like the decade-in-production Sonic the Hedgehog 2 HD; invented whole new entries in the canon, like the unofficial interquel Sonic Before the Sequel; and used the characters to explore themes of internet culture and insular fan communities, as in the surreal Sonic Dreams Collection. These are all impressive projects, some of them damn near equal in quality to the games they’re attempting to emulate. And Sega apparently feels the same way. Around the time Nintendo was issuing cease and desist letters to Metroid and Pokémon fan projects, Sega was hiring Retro Sonic maestro Christian Whitehead to lead development on an officially sanctioned love letter to Genesis-era Sonic.

Recreating, reinterpreting, and remixing elements from Sonic 1, 2, 3, & Knuckles, and CD, and adding heaps of original material too, Sonic Mania is a fusion stir-fry of a video game, a heaping bowl of familiar ingredients prepared in titillating new ways. For lifelong hedgehog apologists like me it’s a vibrant assertion of the series’s greatest strengths, and for skeptics it serves as a crash course in what the Sega kids were always raving about on the schoolyard. The 2010s were heavy on nostalgia, with new remakes and HD remasters coming out seemingly several times a year. But with Mania Sega hit on a winning spin on that formula — something brand new made out of the parts of the old, by fans for fans.

8: The Binding of Isaac (2011)

The Binding of Isaac is ground zero for the 2010s roguelike revival explosion (perhaps sharing the title with 2008’s Spelunky). Without Isaac, there would be no Enter the Gungeon, no Nuclear Throne, no Crypt of the NecroDancer, and no Sparklite. And despite coming first, it has yet to be topped. Isaac‘s compulsive blend of tense exploration, twitchy twin-stick shooting, and long-term strategic planning makes it not just possible but enjoyable to play in true perpetuity. Its infinite replayability has also been helped by its impressively long life. Isaac was already enormous when it quietly debuted in 2011 and has spent the rest of the decade getting even bigger. The game’s massive Afterbirth+ re-release came out as recently as 2017, and its world is now so big that it’s started spilling out into card game spin-offs and match-four prequels.

I generally don’t care for gross-out imagery or toilet humor, but The Binding of Isaac‘s veneer of filth is in service of a unique artistic vision, not the scoring of cheap laughs. Creator Edmund McMillen is candid about the fact that his games’ cutesy-gross aesthetics are his vehicle for delivering disturbing deeper themes and subject matter. Isaac — the story of a naked, abused toddler wading through waist-deep bloody shit to team up with Satan and kill his own mother — is surely McMillen’s magnum opus. To find sacrilege that gleefully flamboyant and nakedly personal, you normally have to look to the stuff the Marquis de Sade wrote while imprisoned in the Bastille. Only in the 2010s could an artistic statement that uncompromising end up a bestseller on Steam and a popular pick among Twitch streamers.

7: No Man’s Sky (2016)

No Man’s Sky might be the game that is most emblematic of the various trends of the 2010s: The universe-sized, math-driven space adventure relies heavily on procedural generation and spontaneously interacting systems to generate its content. It was the subject of a hysterical fan backlash upon its lackluster debut. Its full feature list was rolled out through sizeable expansions over a number of years. It blurs the line between single player and multiplayer. It dabbles in VR. And its visuals seem specifically calibrated to regularly spit out social media-shareable screenshots. If it were also an esport, it would be a clean sweep.

Over the years No Man’s Sky has gone from a barebones survival game about scrabbling for plutonium on interchangeable rocks to a sprawling space opera with numerous play modes unfolding across billions of vibrant biomes. Players can now follow the story of a lost extradimensional pilgrim, aid scientists in their quest to solve the fundamental secrets of the universe, heed the eldritch call of a mysterious obelisk, become titans of industry via trade and base building, or just leg it to the center of the galaxy. But Hello Games face Sean Murray is emphatic that players must find their own way to play, which is just as well, because none of those options interest me. For me, No Man’s Sky is a role-playing exercise, the intrepid journey of a spacefaring nature photographer cataloguing the galaxy for the illustrious periodical Interplanetary Geographic. That’s why I could play No Man’s Sky for the rest of my life — because even after nearly four years it’s never stopped showing me vistas that have me slamming my DualShock 4’s Share button.

6: Hollow Knight (2017)

In the 2010s it became increasingly possible for any old schmuck to make and release a game. It’s totally viable these days to develop in Unity, self-publish through Steam, and use Twitter and YouTube to self-promote. Some of the games produced this way are real gems, either oddball outsider art or avant-garde boundary pushers that would have struggled to find a publisher in previous decades. But plenty of them are just the developer’s favorite Nintendo game with a new coat of paint and an extra gimmick. Games that pay serviceable homage to Super Mario World or The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past are pretty common. Games like Hollow Knight, that blow their legendary influences completely out of the water, are not so common.

Super Metroid and Castlevania: Symphony of the Night are so good and were so influential that the entire Metroidvania genre was named in their honor. I first played Symphony of the Night when I was just nine years old, and I still love it enough to revisit it once a year or so. I have powerful nostalgia for all the Koji Igarashi-directed Castlevania titles, and I adored the self-plagiarizing follow-up he released this year. But even a Castlevania super fan like me is forced to admit that Hollow Knight is simply the best Metroidvania of all time. That a game this beautifully hand-animated and dizzying in scale was made primarily by two guys from Australia is a typically 2010s success story. That it could handily outclass some of gaming history’s most revered and emulated titles isn’t typical of anything — it’s a million-to-one miracle.

5: Undertale (2015)

What is there left to say about Undertale? Coming out the same year as the absolute Thanksgiving dinner of a game that is The Witcher 3, Undertale was made almost entirely by one person, it takes about 10 hours to complete, and vast swaths of it are set in unanimated monochrome voids. And yet, far more than The Witcher, Undertale was a bone fide cultural phenomenon. It notoriously beat The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time in GameFAQs’ “Best. Game. Ever.” poll, a professional wrestler recently did an Undertale-themed entrance without feeling the need to provide his audience any context, and the game’s breakout character got smuggled into Super Smash Bros. when creator Toby Fox literally beat Masahiro Sakurai at his own game. These days Undertale is almost more meme than game.

What’s important to remember looking back though is that underneath the endlessly retold in-jokes, the innumerable remixes of its divine soundtrack, and the mountains of gay skeleton incest porn it inspired, Undertale is just one hell of a video game. On the one hand, it’s a mechanically playful and explosively funny nostalgia exercise, and on the other, it’s a melancholic story about loneliness, desperation, and breaking cycles of violence. Somehow these two diametrically opposed tones beautifully complement one another. Undertale only became a category-5 meme storm because it resonated so strongly with so many people and for so many reasons. And with every passing year, its story of traumatized children using empathy and surreal humor to clean up the mess created by the previous generation’s arrogance rings even more true.

4: Journey (2012)

Games have historically had a bit of an inferiority complex relative to movies. In the mid-2000s, the film world’s most revered critic glibly declared that games could never be art, and for a while after that it became common marketing-speak to describe ambitious games as being like “interactive movies.” Tentpoles of the era like the Grand Theft Auto and Metal Gear Solid games, with their rich cinematography and Hollywood-style action screenplays, certainly seemed to be deliberately aping motion pictures. In the 2010s though, comparisons to cinema became unfashionable as more and more designers embraced the inherent qualities of games and stopped trying to emulate other mediums. This shift was helped, I think, by thatgamecompany widening the net for everybody a little bit. Journey isn’t a video game by way of cinema; it’s a video game by way of poetry.

Journey eschewed almost everything that makes video games video games. It had no combat, no collectibles, minimal exploration, and no loss state. In place of those traditional draws, it offered only pure aesthetics: inventive color palettes, stirring music, and downright balletic animation. It was unapologetic about being little more than a sensory experience — devoid of pretext and with only the barest whisper of a story — that could be exhausted in just two hours. And when those two hours were up it offered nothing in the way of concrete rewards or closure, instead reverting back to its original state, like a prayer that expects to be meditatively repeated. Minimalist indies like Proteus and so-called walking simulators like Gone Home have since made systems-lite design into a decade-defining mantra, but Journey is the original, and still the best, video game tone poem.

3: Bloodborne (2015)

Some of the games on this list are here because they embodied the trends of the 2010s, others because they boldly rejected them. Some of these games are very personal to me, others representing cultural moments. Many of the entries on this list have great stories, while others are purely mechanical exercises and others still are atmosphere-driven mood pieces. Bloodborne is here because it just absolutely fucking rules.

Bloodborne is the closest the industry has ever come to producing a perfect video game. Mechanically airtight, with a rich but unobtrusive story, godly level design, and unmatched art direction, it is the Platonic ideal of an action RPG. Pound for pound Dark Souls might be the single most influential title of the decade, but Dark Souls begins with its protagonist sulking in a dungeon until someone else deigns to rescue them and give them a goal to accomplish. Bloodborne throws an entire werewolf at you before it’s even finished teaching you its controls. Then it thrusts an axe into one of your hands and a gun into the other, gives you a firm slap on the bottom, and sends you out into the streets of Yharnam to start stacking bodies. Everything Dark Souls did to become the most celebrated title of its generation, Bloodborne does better. Plus, you can wear a top hat in it.

2: Bastion (2011)

One day in 2012, when I was a 24-year-old undergrad, it dawned on me with some horror that all my favorite games were games I’d first played when I was between the ages of five and 12. I had enjoyed, even loved, plenty of games I’d played in my teen and adult years, but it had been over a decade since I’d felt the dawning wonder of discovering a new lifelong favorite. I wasn’t cynical enough to think that games were getting less amazing, but I was worried I was losing my ability to be amazed by them. Then, on May 31 of that year, two weeks before my 25th birthday, I bought the Humble Indie Bundle V and never worried about that again. For $20 I got Limbo, Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP, Amnesia: The Dark Descent, Super Meat Boy, and, first among equals, Bastion. Amazing games were still coming out all the time, it turned out; they were just literally all indies.

If any one trend truly defined the last decade, it was the meteoric rise of the indie scene. This trend began a little early — fellow Humble Bundle V title Braid, which arguably kickstarted the modern indie explosion, came out in 2008, and before-their-time visionaries like Cave Story and Yume Nikki were coming out as early as 2004. But in the 2010s, plucky, inexpensive, experimental indies routinely overshadowed the bloated and creatively stagnant offerings of the AAA market. Depending on where you draw the line separating indie games from big studio productions, as many as eight of the entries on this list could be classified as indies. And Bastion is the perfect poster child for the 2010s indie revolution: beautiful and tightly designed, with a tasteful smattering of gimmicks and an absolutely dynamite soundtrack. Bastion was so good it singlehandedly restored my faith in video games.

1: Life Is Strange (2015)

In his review of the already-forgotten Remnant: From the Ashes, the Escapist’s Yahtzee Croshaw proposed that games can be divided into two broad categories: games that make you feel, and games that make you numb. “Some games challenge and energize your emotions and give you ideas and inspiration,” he explained, “whereas other games seek only to massage your rodent brain with repetitive pats to the head so you don’t think dangerous thoughts.” Life Is Strange is my favorite game of the decade, and my favorite game of all time, because it made me feel more than any other game, movie, book, song, painting, or play has ever made me feel.

It’s difficult for me to explain, or even understand, how this happened. Life Is Strange is a damn fine game, sure. It performed admirably, reviewing well, selling over 3 million copies, and accumulating numerous Game of the Year nominations and wins from various outlets. Its frequently but wrongly maligned script is smartly structured, impossible to predict, and endlessly quotable. Its licensed soundtrack, original score, and vocal performances are all decade-best. And the way it uses its central time-rewinding gimmick as both a puzzle-solving tool and a mechanical expression of its protagonist’s indecisive personality is inspired. But a game merely being good, even very good, can’t explain the monumental effect it had on me.

I’m not alone, either. Browsing the game’s subreddit, or its own dedicated fan-made social network, it becomes clear that one in every, say, 500 people who plays Life Is Strange is utterly ruined by it, and none of us seem capable of satisfyingly explaining why. Plenty of people will simply be moved by the game’s sensitive and insightful story of trauma survival, guilt, female friendship, and destiny. But those themes don’t have much purchase with me personally, and the ballad of Max and Chloe still managed to completely upend how I view games, the world, and myself. The year 2015, which gave us The Witcher 3, Undertale, and Bloodborne, plus loads of other great games that didn’t crack my top 10, like Until Dawn, Ori and the Blind Forest, Rocket League, and Splatoon, might be the industry’s all-time-high water mark. But I’ll always remember it for giving me the little game about sad high schoolers in a fishing town that became my single favorite story in any medium.