Inkle co-founder Jon Ingold doesn’t beat around the bush when asked if his team’s new tactical game, Pendragon, is a response to Brexit.

“It is,” he said, “but Brexit is part of a broader political shift.”

In an industry where creators tend to hedge their bets and downplay the politics of their games, his candor is refreshing. But it should come as no real surprise. Over the past few years, inkle has attracted acclaim for telling stories that tackle real social issues like colonialism and sexism with 80 Days and Heaven’s Vault. However, Ingold suggests that political engagement comes not from a top-down agenda, but rather from an interest in the real world.

“I remember when we made 80 Days people said it was a game celebrating diversity, and I always felt that was wrong,” said Ingold. “It was a game about the world, and since the world is diverse, so was the game. To make that game without talking about, say, colonialism would have been just pretending the world isn’t what it obviously is, so what would be the point of that?

“Similarly, Heaven’s Vault is a game about uncovering the past, but the past only matters because it affects the present. … So in Heaven’s Vault, either we tackled the political consequences of our historical understanding… or it was back to archaeologists uncovering ancient alien superweapons yet again.”

He went on to say that his job as narrative director at inkle is “to make games that are actually about what they’re about.” And Ingold was pretty adamant about whether or not games are inherently political: “If you don’t want to do anything political, that’s fine – make a game about squares and blocks. Tetris really isn’t political. But as soon as you have a story, you’re political. I can’t understand why anyone would pretend otherwise.”

Along those lines, on Jan. 31, 2020, the date that marked the official end of the 47-year-long partnership between the U.K. and the E.U., inkle first teased Pendragon on social media. The language used was striking: “Camelot has fallen.”

— inkle (@inkleStudios) January 31, 2020

It was on June 23, 2016 that the United Kingdom citizenry had voted to leave the European Union. The Leave campaign had been brash and bold, spreading rhetoric of British exceptionalism. The E.U. was the reason that the U.K. had fallen, and only by shedding its membership could the country hope to regain its former glory.

That nationalistic fervor galvanized a small majority of the population, but Ingold said that zeal was based on false assumptions: “The stories (we) tell about the past change what we do. Right now in the U.K., stories about the great British Empire have been turning up in the pro-Brexit argument… even though the British Empire was unsustainable and collapsed. Our ignorance of our own history has changed what we’re going to do next!”

Those stories and misconceptions about the E.U. and the British Empire were only part of the equation, according to Ingold. Instead, he said that the Leave campaign was predicated on something more fundamental, something that has come to be endemic across politics in the English-speaking world.

“It was about lies,” said Ingold. “It breached the laws for elections in the U.K., it was dishonest, and it paid off. The men who ran it now run the country. … Lying (used to be) the red line they couldn’t cross, because the media would catch them out. The red line has gone. It is now easier to lie than to tell a half-truth.”

Pendragon takes this concept as its central theme. Nonetheless, inkle continues to identify itself as a global developer, even while it tells stories with a distinctly British flair. Pendragon will embody this notion even more than previous projects by drawing upon British mythology and Arthurian legend.

Pendragon started out as a personal project from designer Tom Kail, a competitive tactics game that proved to be “sticky,” according to Ingold.

“It wasn’t perfect, but we’d sit around at lunch breaks, playing games and arguing over rule tweaks,” said Ingold. “We tried everything, broke it a thousand ways, and after about a year Tom had something that was still the same game, but it was really, really tight. Simple, elegant, but always different, and often nail-biting.”

Kail ultimately agreed to let Ingold create an AI opponent and a narrative component, which led to further iteration. Pendragon was intended to be a “short, simple project after Heaven’s Vault,” but then it of course grew.

Meanwhile, the narratives of good versus evil so prevalent in myth agreed with the style of gameplay very well.

“The Arthurian setting is something I’ve always loved, and it fitted the basic rules of the game well enough,” said Ingold. “The black-vs.-white of chess made us think of doing a game of ideological conflict. The rise and rise of actual fascists in the real world made us think about a game about trying to stay honorable while fighting the dishonorable. All of that swirled together, and out came Pendragon.”

With those fundamentals in place, Ingold has moved along to iterating on the story by delving deep into source material and those past tellings of the Matter of Britain.

“I’m loving working through the Arthurian sources now,” he said. “They’re brilliantly varied. Tennyson’s Victorian tub-thumping, T. H. White’s elegy for sanity in the face of Nazism, the bizarre and beautiful Welsh Mabinogion, Mallory’s curious episodic weirdness. We’re picking and choosing, mixing and remixing. It’s a lot of fun.”

If the team’s work on 80 Days is any indication, inkle is likely to deliver an Arthurian story that shatters all expectations. For starters, Pendragon begins after the fall of Camelot and the end of the golden age. Yet the game is still distinctly about hope.

“Even after everything goes wrong, the sun still comes up and people can still work together,” said Ingold. “(Concurrently), the New Delhi police are beating protesters up in the streets while Muslim households are being broken into by unchecked mobs. And strangers are offering each other sanctuary in their homes. Politics fail, but people are still amazing.”

Hope like this is required in these troubled times for inkle, where small policy changes in the U.K. could be devastating. “If U.K. / U.S. withholding tax treaty disappears, all UK-based studios will immediately lose 20-30% of their Steam income to U.S. tax,” said Ingold. “That would kill a lot of British indies overnight.”

Even with those concerns, Ingold continues to look forward. The company has multiple prototypes in the hopper and has no intention of stopping. In fact, Ingold spoke of at least two projects that he’s confident will see the light of day: something called Highland Run, which inkle co-founder Joseph Humfrey is leading, and a Treasure Island game that Ingold has been wanting to make “forever.”

First, though, Pendragon needs to be completed, and Ingold explained why that has taken longer than anticipated with a comment almost guaranteed to excite fans of inkle’s previous games.

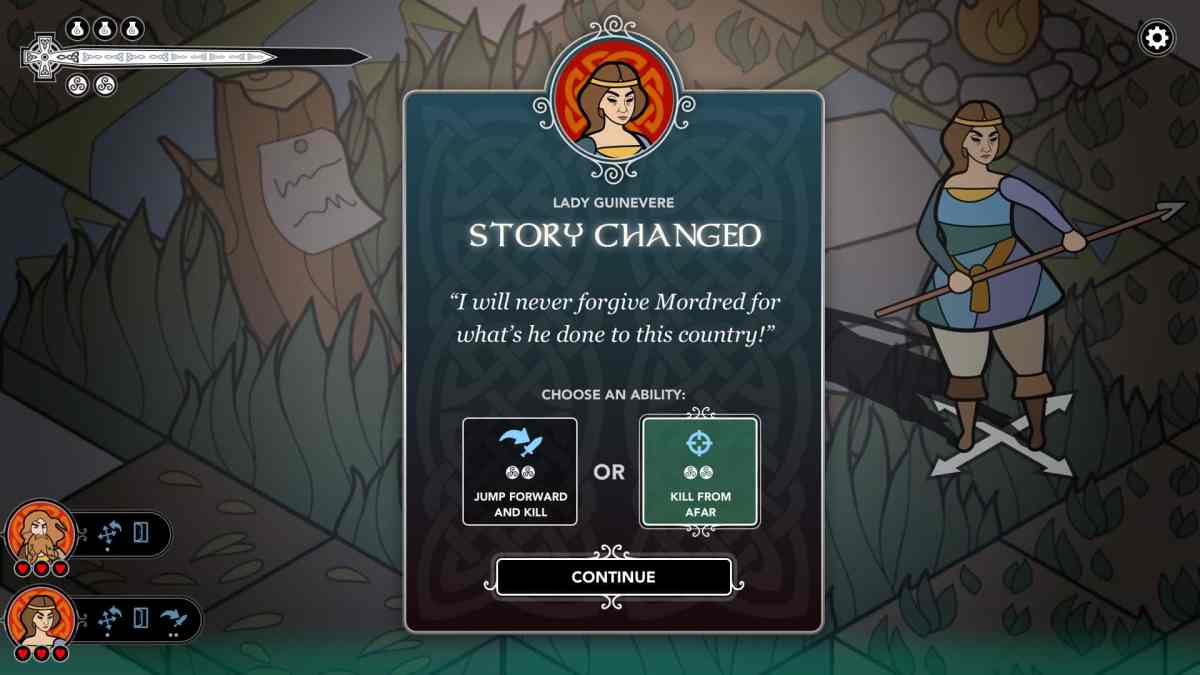

“It’s our most ambitious dynamic, replayable narrative yet,” said Ingold. “Every playthrough is unique. Beyond the first level of the first game, nothing is fixed. Different heroes combine in different ways, in different locations, to have different discoveries, adventures and relationships.

“But none of it is procedurally generated. It’s all authored, tweened together by the ink engine on the fly in response to what you do. When we start a game of Pendragon we have no idea where it’s going to go, except there’s always a tragedy waiting at the end. A bit like Brexit, then.”